Letting Go of Your Story:

Learning from Traudl Junge

For Sunday February 19, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 43:18–25

Psalm 41

2 Corinthians 1:18–22

Mark 1:1–12

|

Traudl Junge, November 1945. |

As a little Austrian girl Traudl Junge (1920–2002) always wanted to be a ballerina, but a cruel twist of fate ruined those dreams forever. When she learned about a job vacancy in the German chancellery during World War II, she entered a typing competition and to her shock was chosen "by complete coincidence and chance" as Adolf Hitler's personal secretary. "I was twenty-two and I didn't know anything about politics, it didn't interest me." From December 1942 until April 30,1945 when she heard the gun shots of Hitler's suicide in his Berlin bunker, Junge conversed every day with one of the worst psychopaths in human history.

Later she was wracked by guilt for her complicity in the Nazi atrocities, and for "liking the greatest criminal ever to have lived. I admit, I was fascinated by Adolf Hitler. He was a pleasant boss and a fatherly friend. I deliberately ignored all the warning voices inside me and enjoyed the time by his side almost until the bitter end. It wasn't what he said, but the way he said things and how he did things." Just before she died at the age of 81, Junge emerged from the safety of her silence and struggled to make peace with her past. She published her memoirs Until the Final Hour (2002), and gave ten hours of interviews for the documentary film about her life called Blind Spot (2002). In her cameo appearance in the film Downfall (2004) about the final days in Hitler's Berlin bunker, she lamented, "I never thought that fate would take me somewhere I'd never really wanted to be."

The tragedy of Traudl Junge was not her association with Adolf Hitler. How many naive, patriotic twenty-two year old kids could have resisted that job offer? Her tragedy was that for fifty-seven years she remained trapped by her past, full of self-recrimination, and unable to forgive herself. Obsessed by her past, she effectively foreclosed her present and her future. Beyond forgiving herself, we can only imagine her struggle to sense any forgiveness from God, from her fellow citizens, or from the families of six million Jews who were slaughtered in the Holocaust.

In the Scriptures from Isaiah for this week God invites us to do what Traudl Junge could not do. He encourages us to forget the past, and to move beyond painful memories that chain us to regrets, sins, failures, foolish choices, betrayals, resentments, disappointments, unsought tragedy, missed opportunities, and roads not taken:

Forget the former things;

do not dwell on the past.

See, I am doing a new thing!

Now it springs up; do you not perceive it?

I am making a way in the desert

and streams in the wasteland.

The past that darkened Israel's present included defeat, devastation and exile at the hands of Assyria (722 BCE) and then Babylon (586 BCE). Each one of us today has a past history that shapes our present life for good and ill. Parsing your past is essential for healing in the present and hope for the future.

|

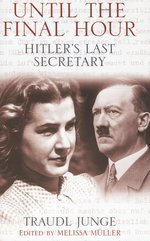

Book cover of Until the Final Hour. |

"Forgetting" your past does not mean ignoring it, denying it, sanitizing it, rationalizing or repressing it. In this sense "remembering" is necessary, good, and healthy. With all the brutal realism, genuine candor, and ruthless honesty that we can muster, we name our past for what it is, claim it as our own, and believe that God will redeem and use it for our good. We also embrace our past with empathy and tenderness for the human condition. Our goal is not shame, blame, fear, exposure, or sadness, but liberation from obsessing about the past in ways that paralyze our present and obscure God's future for us.

The Psalm for this week provides an interesting case study. As I read him, David's prayer zigzags in a schizophrenic manner. He begins with an admirable confession: "O Lord, have mercy on me; heal me, for I have sinned against you." But then he boasts about his "integrity" and equates his fortunate circumstances with divine endorsement. He savors dredging up past slights, slanders, and betrayals by both friends and enemies. In his self-righteousness, David remembers his past as an opportunity for revenge rather than for reconciliation: "Raise me up, that I may repay them." Perhaps David wrote this psalm before he slept with Bathsheba and murdered her husband Uriah? He sounds incapable of forgiving or forgetting. Wallowing in your past to right every wrong or to settle every score is as bad as pretending that your past never existed in the first place.

If we have remembered rightly and repented accordingly, the Gospel invites us to forget the past. "Let us draw near eagerly to Christ," advised St. Makarios of Egypt (5th century), "and let us not despair of our salvation. For it is a trick of the devil to lead us to despair by reminding us of our past sins." As if to show us the way, God himself says in Isaiah that He has forgotten Israel's past transgressions and that he will "remember your sins no more." If God can forget, so can we.

|

Traudl Junge, 2002. |

When the apostle Paul wrote to his young protege Timothy he was an old man, perhaps near death. But even in his later years he remembered his past to Timothy with remarkable candor: "I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and a violent man." Thus he considered himself "the worst of sinners"(1 Timothy 1:13). In Luke's telling, Paul participated in the stoning of Stephen (Acts 8:1). Having acknowledged his sordid past, though, Paul put it behind him, and lived in the present with an eye toward God's future: "One thing I do: forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward in Christ Jesus" (Philippians 3:13–14).

In a poignant coincidence, Traudl Junge died of cancer the evening that Blind Spot premiered at the 2002 Berlin Film Festival. Although she took early retirement due to severe depression, I like to believe that she made peace with her tortured past. Othmar Schmiderer, the producer of Blind Spot, was among the last people to speak to her. He quoted Junge as saying: "Now that I've let go of my story, I can let go of my life." So too does God invite us to "let go of our story," to embrace and then move beyond our past in confident expectation of His gracious future.

For further reflection:

* Watch the film Blind Spot with family or friends.

* How do you engage and understand your past?

* Identify both healthy and unhealthy ways that we both "remember" and "forget."

* Consider: in Mark's Gospel this week friends brought a paralytic to Jesus for healing; He offered forgiveness and only later healed him.