The Bottom Billions: Terror on Every Side

For Sunday March 20, 2005

Sixth Sunday in Lent, Palm Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 50:4–9

Psalm 31:9–16

Philippians 2:5–11

Matthew 26:14–27:66

|

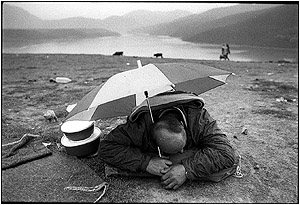

Kosovo refugee by James Nachtwey. Photo from Life Magazine. |

In the foreword to Paul Farmer's book Pathologies of Power; Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor (2003), the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen cites a World Bank study from 1993 that "in sub-Saharan Africa, the median age at death is less than five years." To forestall disbelief, Sen assures readers that this is not a typographical error. Today about half of that continent's 800 million people live in what the World Bank defines as "absolute poverty" (income of less than $1 a day). For that matter, Sen observes, in our wealthiest American cities like New York, some African Americans have a shorter life expectancy than many people in China or India.

Last week the cover story of Time (March 14, 2005) featured excerpts from Jeffrey Sachs's new book The End of Poverty (2005). "More than 8 million people around the world die each year because they are too poor to stay alive," writes Sachs. "Every morning our newspapers could report, 'More than 20,000 people perished yesterday because of extreme poverty.'" For about half of the world's 6 billion people, the elementary right to survive is under assault.

How have these deplorable disparities between our rich minority and the majority poor emerged? How has it come about that 17% of the world's population consumes 80% of the world's resources, leaving almost 5 billion people, the other 83%, to live on the remaining 20%?1 Are these simply random distributions of economic history and therefore accidental? Maybe they are inescapable, even somehow necessary? Does God will these disparities, such that people should be content with their lot in life? Or maybe rich people are smarter and work harder than poor people? After ministering in El Salvador for the last forty years, the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino (born 1938) has come to a different conclusion: "The poor of the world are not the causal products of human history. No, poverty results from the actions of other human beings".2 Choices that we have made, individually and collectively, personally and politically, have caused this situation.

|

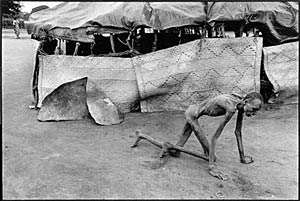

Starvation in Sudan, by James Nachtwey. |

In his magisterial if flawed new book Collapse (2005), Jared Diamond identifies five factors that have led to the catastrophic demise of a broad range of civilizations—large and small, ancient and modern, peripheral and advanced. Allowing for some complexities, all five factors could be reduced to human choices: environmental impact (here he lists 12 factors like deforestation, water management, etc.), climate change, hostile neighbors, the loss of friendly neighbors (eg, trade partners), and human responses to these problems. In his chapter on big business and the environment, for example, he concludes that since businesses have a fiduciary obligation to maximize shareholder profits, it is up to the public, not the businesses, to hold them accountable. He admits that, in the end, this particular conflict boils down to competing cultural values (profits v. the planet) that inform and determine the human choices we eventually make.

So, the brutal economic asymmetry that consigns half of the world to wretchedness is not accidental. Much of it is remediable, preventable, and curable. With different values and priorities that would inform different choices, for example, the United States could choose to see abject poverty as a threat to global security, which it is, and redirect some of the $500 billion that it will spend on the military this year and supplement the $16 billion it will spend on the poorest of the poor. We could choose to reverse the trend of the past few decades and increase rather than decrease the amount that we have pledged, and often failed to give, to help the world's poor.3 National and personal budgets, Jim Wallis has observed, are thus moral douments in the sense that they reveal the priorities about which we care most.

We know that our social, eeconomic and cultural location "colors" and sometimes even determines what we see, how we think, or the manner in which we read a text like the Bible. Consider the Psalm for this week:

Be merciful to me, O Lord, for I am in distress;

my eyes grow weak with sorrow,

my soul and my body with grief.

My life is consumed by anguish

and my years by groaning;

my strength fails because of my affliction,

and my bones grow weak.

Because of all my enemies,

I am the utter contempt of my neighbors;

I am a dread to my friends—

those who see me on the street flee from me.

I am forgotten by them as though I were dead;

I have become like broken pottery.

For I hear the slander of many;

there is terror on every side;

they conspire against me

and plot to take my life (Psalm 31:9–13).

As a wealthy, white person living in Palo Alto, this Psalm might provoke me to pray that my child gets accepted not just to a good university but a great university, that that my other child finds a well-paying job, or that my wife's orthopedic surgery to correct a ski injury will succeed (all prayers I have prayed). But if I were a child sleeping on the floor of the Jakarta train station, a woman in Bihar, India, emptying human feces from latrines, or a scavenger combing through Manila's municipal garbage dump to find my family's next meal, I would read, think about, pray, and experience this Psalm far differently.

|

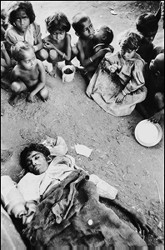

Bombay street children by Dario Mitidieri |

The epistle for this week includes one of the earliest songs that the first Christians ever sang, part of which says that Jesus "emptied himself" of his divine prerogatives to condescend to our human condition (Philippians 2:7). Elsewhere Paul uses an economic metaphor when he writes that although Jesus was rich, yet for our sakes he became poor, that we through his poverty might become rich (2 Corinthians 8:9). As an old man Paul said that his own life had been "poured out like a drink offering" for others (2 Timothy 4:6). Part of identifying with Jesus and patterning our lives after him asks the same of us—divestment of wealth rather than accumulation, renunciation rather than gratification, self-sacrifice rather than self-satisfaction, and at a minimum something akin to what Paul Farmer describes as "pragmatic solidarity" with the poor.

The Christian church has often sided with the wealthy and the powerful. But at our best many believers have chosen the counter-cultural option of following Jesus in identifying with the poor. When the Apostle Paul sought the approval of the leading apostles, they demanded a singular priority: "All they asked was that we remember the poor, the very thing I was eager to do" (Galatians 2:10). About a century later the early Christians had a well-known and well-deserved reputation for caring for the weak. Tertullian (AD 155–220), for example, wrote, "Our care for the derelict and our active love have become our distinctive sign before the enemy...See, they say, how they love one another and how ready they are to die for each other." Even the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate (ruled AD 361–363), who vehemently opposed Christians and stripped them of their rights and privileges, acknowledged the early Christian option for the poor: "The godless Galileans feed not only their poor but ours".4

Commenting on Matthew 25:31–46 where God judges "all the nations" according to how they served the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, and the prisoner, James Forbes, pastor of Riverside Church in New York City, puts it rather bluntly: "Nobody gets to heaven without a letter of reference from the poor."

[1] http://www.worldcentric.org/stateworld/socialjustice.htm.

[2] Cited by Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), p. 143.

[3] See Time, March 14, 2005, p. 46.

[4] Cited by Ron Sider, The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), p. 52.