Bette Midler Was Wrong

For Sunday December 19, 2004

Fourth Sunday of Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 7:10–16

Psalm 80:1–7, 17–19

Romans 1:1–7

Matthew 1:18–25

|

Joseph with Jesus by Guido Reni, 1635 |

Whatever else the Christmas Season brings besides weight gain and credit card debt, some time or another our exaggerated expectations of holiday cheer will clash with the harsh realities of life as most of us live it. The result is a gnawing sense of the disconnect between what is and what should be, between what we long for and what we experience. For some this disconnect is so profound and deeply personal that it leads to clinical depression.

In a favorite song of mine, Bette Midler captures this deeply human but ambivalent sense of longing. From a sanitized "distance," life feels safer and better than what we experience up close and personal.

From a distance,

The world looks blue and green,

And the snow capped mountains white.

From a distance,

The ocean meets the stream,

And the eagle takes to flight.

From a distance,

There is harmony,

And it echoes through the land.

It's the voice of hope,

It's the voice of peace,

It's the voice of every man.

From a distance,

We all have enough,

And no one is in need.

And there are no guns,

No bombs and no disease,

No hungry mouths to feed.

From a distance,

We are instruments,

Marching in a common band,

Playing songs of hope,

Playing songs of peace,

They are the songs of every man.

From a distance,

You look like my friend,

Even though we are at war.

From a distance,

I just cannot comprehend

What all this fighting's for.

From a distance,

There is harmony,

And it echoes through the land.

And it's the hope of hopes,

It's the love of loves,

It's the heart of every man.

Chorus:

God is watching us,

God is watching us,

God is watching us,

From a distance.

Such is life at arm's length, or at the dramatic "distance" between human longing and empirical reality.

|

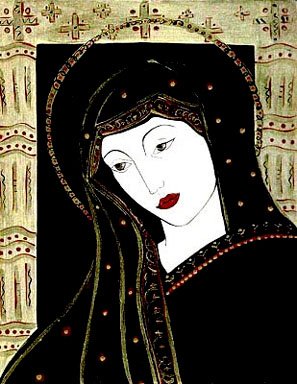

Black Madonna |

Up close, where most people really live, life is different. In its recent report, "Health, United States 2004," the Center for Disease Control reported that almost half of Americans (44%) take at least one prescription medicine. In Business Week (December 6, 2004), the Economic Policy Institute reported that in 2003 the average chief executive had to work a mere day and a half to earn the equivalent of a typical employee's yearly salary. In addition to these elusive hopes of physical health and economic equity, we also fail ourselves. I resonate with the Benedictine nun Joan Chittister, who in her new book Called to Question: A Spiritual Memoir (2004) wrote, "We know ourselves to be weak. We stumble along, being less than we can be, never living up to our own standards, let alone anyone else's. We eat too much between meals, we work too little to get ahead, we drink more than we should at the office party. We're all addicted to something. Those addictions not only cripple us, they convince us that we are worthless and incapable of being worthwhile. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy of the worst order because it traps us inside our own sense of inadequacy, of futility, of failure."

For its part, the Scriptures, especially the Psalms, are brutally realistic. The Psalmist for this week sounds like Bette Midler when he decries God's anger "smoldering against the prayers of his people." As a result, he speaks of "drinking tears by the bowlful" (80:4–5). Facing the devastation of civil war, Isaiah writes that "his people were shaken, as the trees of the forest are shaken by the wind" (Isaiah 7:2).

The truly Good News at Christmas is that Bette Midler was wrong. Whatever else the Christian God is, He is not a distant or detached deity. He is not silent, aloof or remote. The Distant Deity is a sad relic of 18th-century Deism, which held a firm belief in God but then relegated him to the status of an absentee landlord who never meddled in human affairs. In the Gospel for this week, when Matthew searched for a way to distill the essence of that first Christmas, he reached back 700 years to borrow a single verse from Isaiah 7:14, and even one single Hebrew word: "The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel"— and then Matthew translated that Hebrew word for his readers, adding, "which means 'God with us.'"

|

Asian Madonna |

In that single Hebrew word Immanuel, God with us, resides the essence of what Christians believe happened at the birth of Jesus. In a divine descent, God took on human flesh and entered our world to embrace and redeem us. Whether we feel His presence or not, He is near us. Even though "we all stumble in many ways" (James 3:2) and do not merit His favor, He is near us. Nothing we say or do could draw Him closer or drive Him away. Regardless of what we have done or left undone, said or left silent, God is near to us.

Confident of His nearness, for each of us individually, but also for all the world, Christians are the ultimate optimists. In the words of the Christmas hymn "Joy to the World" by Isaac Watts (1674–1748), we believe that God's nearness signals that "He comes to make His blessings flow, far as the curse is found."

My Christmas prayer this year comes from Phillips Brooks (1835–1893), one of the country's greatest preachers of the 19th-century and the person after whom Phillips Brooks House at Harvard is named:

O holy Child of Bethlehem, descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in, be born in us today.

We hear the Christmas angels, the great glad tidings tell;

O come to us, abide with us, our Lord Immanuel.

To Journey with Jesus readers over 50 countries around the world, IMMANUEL!