I Pledge Allegiance

For Sunday December 5, 2004

Second Sunday of Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 11:1–10

Psalm 72:1–7, 18–19

Romans 15:4–13

Matthew 3:1–12

|

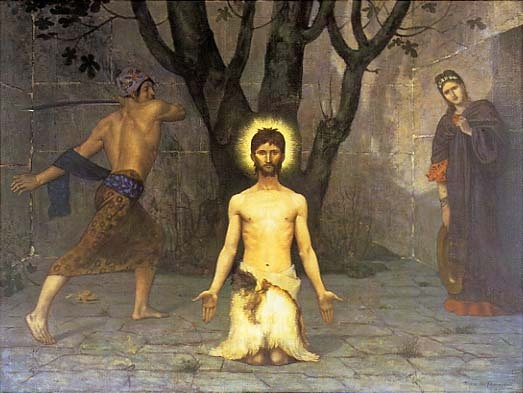

The beheading of John the Baptist by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1869) |

What did the Muslim mechanic Seif Adnan Kanaan, the American Jew Daniel Pearl, and the Buddhist village leader Jaran Torae of Thailand all have in common? They were all beheaded by radical Muslims. The horror of beheadings has been so effective that they have spread as far as Haiti, where a group loyal to ousted president Jean-Bertrand Aristide has launched a terror campaign called “Operation Baghdad” and beheaded three police. In fomenting terror in the hearts of people, some of these extremist groups claim that their political atrocities are divinely mandated.

When I think about Advent I do not normally think of beheadings, but the connection is uncomfortably closer than you might imagine. The most famous Advent herald of all was beheaded. The Gospel for this week tells the story of John the Baptist, a wild sort of man who lived in the desert, wore animal skins, ate locusts, and announced the dawn of God's rule and reign (Matthew 3:1–12). His proclamation was deceptively simple and deeply subversive: “repent and believe, for the kingdom of God is at hand.”

John the Baptist announced the claims of God’s kingdom upon our lives as ultimate, which means that the claims of race, gender, culture, economics and, yes, political and state allegiance are, at best, penultimate. The earliest and most radical Christian confession was simply "Jesus is Lord." This was essentially John’s Advent proclamation, and by direct implication caesar is not lord or god. For other early believers, because of their many martyrs, the Roman state was not only not divine; they described it as the apocalyptic beast from hell (Revelation 13). When you criticize state power, you are lucky if you are only scorned as unpatriotic; if you are unlucky and the state feels sufficiently irritated or threatened, you could be beheaded. King Herod beheaded John the Baptist, the first Advent herald, after he told Herod that he should not sleep with his brother Philip's wife (Matthew 14:1–12).

At Advent Christians celebrate their belief that in Jesus “the Word became flesh and lived for a while among us” (John 1:14). We believe that in Jesus “the light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5).

Across the last two hundred years many (most?) of our presidents have appropriated the language of the Gospel to describe and legitimize the nature and mission of America. I have just read David Donald's biography of Lincoln, who of course was famous for his use of Biblical themes in presidential speeches. Reagan spoke of America as a "city on a hill" ( = Matthew 5:14). Clinton invoked the idea of a "new covenant" ( = Jeremiah 31:31). On the first anniversary of the September 11 tragedy, Bush finished his emotional speech with a flourish: “This ideal of America is the hope of all mankind. That hope drew millions to this harbor. That hope still lights our way. And the light shines in the darkness. And the darkness will not overcome it. May God bless America." Notice how President Bush quoted John 1:5, but with one extraordinary change—he substituted America for Jesus Christ. For John the Baptist, the Advent message is that Jesus alone is the light of the world and the hope of the world; Bush described America as that light and hope.

I suspect that these four examples are little more than the common invocation of biblical rhetoric that many presidents have utilized across two centuries. Still, when Lincoln, Reagan, Clinton, Bush and other presidents intimate that God's kingdom and America are interchangeable words, I get nervous. At best, Bush’s language is careless, so much so that even the conservative theologian and political commentator Richard John Neuhaus of First Things lamented the analogy from John 1:5. If all these many presidents did intend more than mere rhetorical flourish, then Christians are right to object that, for them, to substitute the nation-state for the Almighty veers toward idolatry and blasphemy. Islam might want to join together the throne and alter into a theocracy, but not Christianity.1

|

Thomas More by Hans Holbein (1497-1543) |

Christians insist on a simple but profound point: the realm of nationalist and state power is not co-terminus with the kingdom of God that John the Baptist announced that first Advent season. The state has often rejected this distinction as intolerably subversive. To take a Christian beheading as an example, when the Catholic Thomas More (1478–1535) refused to acknowledge that the Protestant Henry VIII was head of the Church of England, he was beheaded. Tradition has it that his last words were, “The king’s good servant, but God’s first.” Yes, we honor the king, More suggested, but our ultimate pledge of allegiance is to the kingdom of God.2

|

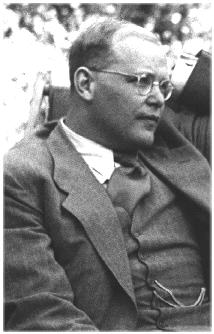

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) |

Closer to our own day, during the Advent season of 1943 the Lutheran pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945) was imprisoned in a Nazi prison camp. In what eventually was published as his Letters and Papers from Prison he admitted that given his circumstances he resonated more with the Old Testament, where the promises of God were seen only at a distance, than with the New, where those promises were finally realized.3

Unlike Kanaan, Pearl and Torae, and more akin to John the Baptist and More, Bonhoeffer was not an innocent bystander. In the spring of 1943 he was arrested and imprisoned for helping to smuggle fourteen Jews to safety in Switzerland. As a double agent in the German military intelligence, he kept Britain informed about Resistance plans to kill Hitler. He openly admitted that he was an implacable foe of Hitler’s National Socialism that demanded allegiance to the state above his Christian allegiances. He was, in fact, working for the defeat of his own nation. For that treason he was hanged by special order of Himmler on April 9, 1945, just a few days before the Allies liberated the concentration camp at Flossenberg where he had been held. Three other members of his immediate family were also executed by the Nazis for their resistance to Hitler.

With his announcement that the kingdom of God is at hand, John the Baptist counseled us to repent of anything and everything that might hinder ultimate allegiance to Jesus. Let us follow his counsel to repent, especially of whatever ways we have confused and conflated the legitimate realm of the state, which we are supposed to honor, with the ultimate claims of God, to whom alone we offer all we have and are.

[1] In the last two paragraphs I have followed Stephen Chapman, "Imperial Exegesis; When Caesar Interprets Scripture," in Wes Avram, editor, Anxious About Empire; Theological Essays on the New Global Realities (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2004), pp. 91–102.

[2] For a fine statement of this theme, see "Confessing Christ in a World of Violence" signed by more than 200 theologians.

[3] See Robert Johnston, Useless Beauty (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2004), p. 71.