Far From Home: Exile

Week of Monday October 4, 2004

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 29:1, 4–7

Psalm 66:1–12 or 2 Kings 5:1–3, 7–15

Psalm 111

2 Timothy 2:8–15

Luke 17:11–19

|

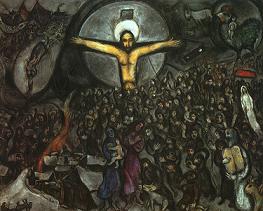

The Exodus by Marc Chagall |

In my Bible the Hebrew Old Testament runs about 1300 pages long, and I suspect that many a well meaning person who had vowed to read straight through the entire Scriptures bogged down somewhere before the New Testament. I know I have. But at the risk of oversimplification, we might say that Yahweh's long drama of salvation with his elect people Israel revolves around two major acts. First, after 430 years of bondage, there is the triumphant Exodus from Egypt some time around 1400 BC. Then, eight hundred years later, there is tragic Exile to Babylon in the year 586 BC. These seminal events of exodus and exile reverbate throughout both the Old and New Testaments as two paradigms or models of the way God works in human history, and even in our own personal histories.

The Exodus story begins with Yahweh's call of the reluctant Moses and culminates with a flourish in the triumphant song of the prophetess Miriam (Exodus 3–15). It is a drama of liberation from oppression and exploitation, of miraculous deliverance, of God's mighty acts of power in regal display, of His dramatic intervention to shatter the enemy, work wonders, and break the powers of bondage. No wonder it is mentioned throughout the Bible as a reminder of God's power to save, and celebrated at Passover even today by Jews. The Psalmist for this week proclaims, "How awesome are your deeds!" (Psalm 66:3). The Exodus story reminds Christians that we have every reason to hope and pray for Yahweh's dramatic acts of salvation, both in the world at large and also in our personal lives.

But then there is Exile. For the pious Hebrew, deportation to pagan Babylon was unthinkable, beyond comprehension. What in the world had happened? Where were Yahweh's mighty acts of power? Was not Israel God's inviolable and elect people, and if so how could He relinquish them to a pagan nation? Exile to Babylon began a period of subjugation, servitude, banishment and captivity. It signaled failure, isolation, loneliness, and even punishment. Certainly it meant despair, for the elite Jews who were deported and for the common people of the land left behind in the rubble of Jerusalem.

How was a Hebrew deported to Babylon, torn from home and everything familiar and dear, to understand his exilic situation? In the lectionary for this week the prophet Jeremiah counsels advice that is both counter-intuitive and entirely revolutionary. Writing from besieged Jerusalem, he sends a letter to the exiles who had been forcibly relocated to Babylon. Here is what he wrote (Jeremiah 29:4–7):

This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says to all those I carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon: "Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the Lord for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper."

In essence, Jeremiah tells the exiles to embrace their disaster rather than to resist it. They must let go of their past and accept their new circumstances, however unthinkable. He advises them that contrary to all appearances, at this moment in Yahweh's story of salvation, they are better off in pagan Babylon than left behind in holy Jerusalem. God is still working, only now in the most unlikely of ways and in the most improbable of places.

Celebrating God's mighty acts of power, His decisive miracles of deliverance, is easy. Who does not long for their own personal exodus, punctuated by a divine exclamation point, whether that be for work, at home, a marriage, finances, children—the list is nearly endless. But we know that sometimes things do not work out as we wish, or as we think they should, or as we pray. History can take a bitter turn. Catastrophe can overtake us, sometimes of our own making, other times for no apparent reason at all.

Living in exile, far from home, bereft of all one considers good and familiar, is difficult. Living in exile demands revised expectations. Courage to believe that God is still at work, no matter how bleak the circumstances. Learning a new language and grammar, much as the Jews settling into Babylon learned a new tongue, to articulate your lived experience. Perseverance over the long haul. Living in exile also requires hope about the future, no matter how dark the present. That, too, was part of Jeremiah's message from Yahweh, just a few verses later (29:11): "For I know the plans I have for you," declares the Lord, "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future." But this future was far off for those Babylonian exiles, seventy years and two generations before the Persian king Cyrus would rout the Babylonian regime and permit the Hebrews to return home. Hope for the future is also an admission that we cannot have it all now in the present. Some of the exiles never returned home.

Living in exile, far from home, bereft of all one considers good and familiar, is difficult. Living in exile demands revised expectations. Courage to believe that God is still at work, no matter how bleak the circumstances. Learning a new language and grammar, much as the Jews settling into Babylon learned a new tongue, to articulate your lived experience. Perseverance over the long haul. Living in exile also requires hope about the future, no matter how dark the present. That, too, was part of Jeremiah's message from Yahweh, just a few verses later (29:11): "For I know the plans I have for you," declares the Lord, "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future." But this future was far off for those Babylonian exiles, seventy years and two generations before the Persian king Cyrus would rout the Babylonian regime and permit the Hebrews to return home. Hope for the future is also an admission that we cannot have it all now in the present. Some of the exiles never returned home.

One mistake that was easy to make was to think that Yahweh, who called Israel as His elect people and covenanted Himself to them, worked only in Israel. Jeremiah reminds us that He is at work always and everywhere, in exodus from Egypt to be sure, but also in exile to Babylon. Two other texts about foreigners from this week remind us not to limit the sphere or scope, the ways or means, of God's saving power. First is the healing of the pagan military leader Naaman, a leper, who after his healing returned to offer his worship to Yahweh, however imperfectly, from the pagan temple of Rimmon (2 Kings 5). Then, in the Gospels we read about Jesus healing the ten lepers (Luke 17:11–19), and how only the Samaritan foreigner returned to give thanks.

Christians should never forfeit the hopes, dreams and prayers for exodus deliverance, but neither should we forget the exilic motif of living under a yoke and in banishment. Human experience assures us that we will need the latter paradigm as well as the former. The English convert to Catholicism, and eventual Cardinal, John Henry Newman (1801–1890), captures these exilic motifs in his famous hymn "Lead, Kindly Light" (1833), which he wrote while at sea in a period of profound loneliness.

Lead, kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home--

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene—one step enough for me.I was not ever thus, nor prayed that Thou

Shouldst lead me on.

I loved to choose and see my path; but now,

Lead Thou me on!

I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears,

Pride ruled my will: remember not past years.So long Thy power hath blessed me, sure it still

Will lead me on,

O'er moor and fen, o'er crag and torrent, till

The night is gone;

And with the morn those angel faces smile

Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile.

There are periods of darkness and gloom when we feel far from home, and it is natural to pray for exodus deliverance when in the garish light of day we can see our path clearly and make our choices freely. But Newman reminds us that real Christian maturity means putting one foot in front of another, one step at a time. Although we might not see "the distant scene," we remain confident that morning will break, because Yahweh is no less present in exilic darkness than in exodus deliverance.