Book Notes

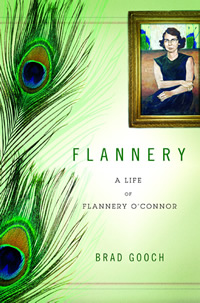

Brad Gooch, Flannery; A Life of Flannery O'Connor (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 448pp.

Brad Gooch, Flannery; A Life of Flannery O'Connor (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 448pp.

Mary Flannery O'Connor (1925–1964) published only two novels — Wise Blood in 1952, and The Violent Bear It Away in 1960, and two collections of short stories — A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories in 1955 and the posthumous Everything That Rises Must Converge in 1965. That output was more than enough for her short life to cast a long shadow across the literary landscape, evidenced by the 195 doctoral dissertations and seventy book length studies of her work. Gooch has written the first major biography of O'Connor since she died, adding to our fund of knowledge from letters that were newly released in 2007 and countless interviews with O'Connor's friends, classmates, colleagues, publishers, and critics.

O'Connor cut an odd figure. From her earliest years as an only child, she was always socially awkward, deeply introverted, and colorfully eccentric. She laced her coffee with coke, enjoyed racist jokes, never married, and collected exotic birds (especially her beloved peacocks). A deeply pious Catholic, she lived in the Baptist south. When she entered college she intended to be a political cartoonist but found her calling at the Iowa Writer's Workshop. After leaving Georgia for Iowa, New York City and Connecticut, her diagnosis of lupus at age twenty-six (the same disease that killed her father when he was forty-five) returned her back to isolation on the 550-acre working dairy farm in rural Georgia run by her widowed mother, from which isolation she wrote powerfully disturbing fiction about human nature. O'Connor was also an exceptionally disciplined writer, establishing early on an inviolable and lifelong regimen of writing three pages a day every morning.

Most of all, O'Connor was one of the most important Christian writers of the last century or more. She attended daily mass most of her adult life, and described herself as "a thirteenth century Christian" and "hermit novelist." Indeed, she read broadly and deeply in Aquinas and other theologians. For her, the craft of her art — good stories well told — was an end in itself and a sign of God's grace. The content of her fiction was also her confession of faith: "My subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil." To those who complained about her grotesque and deeply flawed characters, she insisted that "there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism," and that "to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures."

For the most part Gooch connects the events of O'Connor's life with what he perceives as the autobiographical aspects of her fiction. He acknowledges but does not treat in depth O'Connor's cultural racism (she once refused a visit by James Baldwin) or tense relationship with her overbearing mother who ran the farm as a savvy business woman. I also wish that Gooch had included some of O'Connor's extensive art work among the 16 black and white photos. At the end of this biography, though, I was left with a keen sense of awe and gratitude for a woman who, despite her significant suffering and "passive diminishments" (a concept from Teilhard de Chardin that she liked), stayed true to her call and her God.