Last winter, I wrote an essay honoring my grandmother on the occasion of her 100th birthday. (You can read it here.) In it, I celebrated her years of devotion to God, and described how I'd feel if I lost her. "I fear to let her go," I wrote. "Her faith anchors mine."

Prescient words, but not forceful enough. My grandmother died a few weeks ago, two months shy of another milestone birthday. Since then — how to say it? — the ground hasn't behaved itself for me. It sways under my feet. It trembles, lurches, bucks. It gives way. As a friend said to me recently, it's the nature of ballast to be invisible; we can't know what steadies us until it's taken away.

Those of you who read my essays regularly know that I grew up practicing a conservative, fundamentalist version of Christianity — the version my grandmother observed and cherished all her life. In recent years, I've moved away from that version, into a liturgical and more progressive expression of faith.

But that description is deceptive. It makes the journey sound straightforward, as if my spiritual GPS has offered unambiguous guidance. Head north. Turn left. Continue straight. In two miles, take exit 32B, on the right. You have arrived at your destination.

The reality is devastatingly something else.

My grandmother's death this winter comes hard on the heels of another long grief. My daughter, now sixteen years old, is sick, with a constellation of illnesses that seem, at the time of this writing, intractable. My husband and I continue to seek out every kind of treatment we can. We cry. We plead. We hope. But we also live in shadow, knowing that our daughter might die. Each moment is hard. Each moment is a battle against despair.

I've avoided writing about this crisis, in part to protect our family's privacy, but in part to protect a lie — the lie that I can keep my faith intact despite my daughter's illness. I can't. Whatever happens now between God and me, it will happen — it could only ever happen — in this shadowland.

The morning after my grandmother died, I stayed outside the house and kept my eyes on the sky. It was a gray day, cloudy and dismal, but I didn't care; I was busily imagining sunshine. Also angels in gleaming robes. Also a wide, blue river — the River Jordan, to be precise. I was wondering, quite literally, this: Has it happened yet? Did it happen instantaneously? Is it happening now? When will it happen?

"It" being my grandmother entering heaven. "It" being the sweet reunion of a widow with her long-departed husband. "It" being a mended hip, an end to arthritis, a fabulously restored memory. "It" being my grandmother meeting — at last, at last — the God she loved and worshipped so faithfully for a hundred years.

The ground shook as I wondered these things. My fear is what made the ground shake.

|

The thing is, my grandmother believed in a literal heaven "up there," a real and beautiful place where Christians go immediately upon death. She believed in the Bible as God's inerrant Word, a holy book of promises written expressly for us. She believed in Jesus's substitutionary death and bodily resurrection as the only cornerstones of salvation. She believed in specific and miraculous answers to prayer, divine healing, ecstatic spiritual experience, and the gift of tongues. She believed in the absolute and inviolable will of an all-powerful and all-benevolent God, governing every particular of our lives.

She didn't just believe in these things. She inhabited them. They were the walls, windows, ceilings, and doors of her life.

Here's what my lurching ground feels like: I used to believe every single thing my grandmother believed about God, Christianity, and the spiritual life. I used to have a religious home as solid and certain as hers. To say that I have left that home is true. To say I had no choice — honesty compelled me — is truer. But the truest thing is this: I long to go home. I long to know where home is.

For the past few years, I've told myself that my grandmother's version of faith is no longer available to me, and that I'm okay with that. Because it's true. In theory, I'm perfectly okay with metaphor and mystery. In theory, I've moved past an anxious need for dogma, for certainty, for bedrock absolutes. In theory, I can hold my faith at a clinical distance from the messy particulars of my life.

But then the earth buckles, and I understand. Death is not theory, and neither is a sick child. Nothing is okay when I stare at the clouds, looking for my dead grandmother, and no longer know what to hope for. Will I see her again? Is she up there? What does eternity mean now?

Nothing is okay when I hold my daughter up to God night after anguished night, and find no comfort in mystery. Nuance aside, I want answers. Clear bottom lines. Are the New Testament healings real or not? Are the promises of Scripture meant for us or not? Is God all-powerful, all-good, and all-knowing, or not?

Will you heal my baby? Or not?

It's impolite to pose the questions so baldly. When I asked a priest I respect very much if he believes in a literal afterlife, he hemmed. He knew I was asking about my daughter, and his sorrow was etched into every line of his face. "I believe in Love," he said cautiously. "I believe in God's deep, deep Love, which is stronger than evil, sickness, or death."

"That's nice," I snapped, fighting back tears. "But what does it mean? And why on earth is it enough?"

We don't know what gives us ballast until it's gone. We don't see what we're made of until we're unmade. We think we're okay, we think we're strong — and then the ground begins to shake. The earth heaves, our feet slip, and we grab wildly in all directions at once: backwards, forwards, sideways, down. Where is safety? Whom do I belong to? What is real? Where can I go?

I didn't know my grandmother was a placeholder. Keeping a thousand fears at bay with a faith I still admire, but can't sustain.

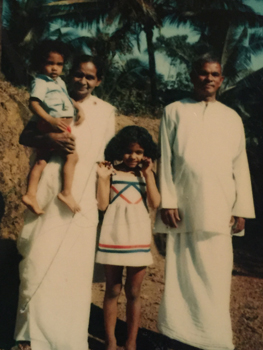

She died in the same village in Kerala, South India, where she spent most of her life, in a house built on the same ancestral land where she arrived as a teenage bride, raised six children, and eventually lived out the thirty years of her widowhood. But our extended family is large, and scattered now across several continents. We couldn't all return to Kerala for her burial.

So a week after my grandmother's death, in the middle of the night here in California, I found myself curled up tight on my bed, my laptop propped beside me, watching a livestream of her funeral. It was an experience unlike any I've had before — disorienting, piercing, raw. I was, at once, there and not there. Connected and disconnected. In community, but alone.

I am grateful for the technology that made it possible for me to witness the funeral at all. But as I sat on my bed, gazing at a grainy image on my computer screen, I remembered my childhood trips to India, the way my parents, brother, and I would take an autorickshaw into my grandmother's village after our long, trans-Atlantic flight from the U.S. The village didn't have reliable electricity, so we'd hazard the winding dirt roads in the pitch darkness, our eyes hungry for a first glimpse of the family house. We'd peer and strain, looking, looking. Finally, we'd round a corner — and there my grandmother would be, standing in the courtyard in her usual gleaming white, a tall candle burning in her hand.

|

She'd usher us in, caress our faces, hold us tight. For her, all of it was miracle — the foreign country we'd returned from, the plane — chairs in the sky? — the impossible ocean crossing. The first words I'd hear her breathe were always, "Praise God."

I miss her in the flesh. I miss her long fingers on my face. Her sweet smile. The way she smelled of coconut oil, lotion, and spices. But I also miss the comfort of Presence. Of welcome. Of return. The assurance that no matter where I go, or how far I wander, I can always make a journey home.

The same friend who spoke so wisely of ballast sent me a gift last year. It's a cartoon, in black and white, of a funny-looking man fending off a little girl. The man has his arm extended, his long fingers pressed against the forehead of the child. There's a look of supreme — acceptance? patience? amusement? — on his face. But the girl is fury personified. Pigtails flying, fists and teeth clenched, feet moving so fast they never even touch the ground. She's headed for the man with all the spitfire ferocity of a bull aimed at a red cape, and though her arms are far too short to reach him, it's clear she's determined to knock him to the ground.

"It's you," my friend explained when she sent the gift. "It's you, fighting God."

She's right; it's what I do. I fight with God. Like Jacob in the pre-dawn darkness, wrestling the angel for a blessing, I ram my whole conflicted self into my Maker. I throw myself against his maybe-patient, maybe-amused self over and over again, until war is all I know. I do this in my writing, in my thoughts, and through my prayers. Every step of my faith journey has been combative. A pitched and desperate battle.

It's not a bad thing. After all, to fight is to engage, to keep my arms wrapped tight around my opponent. Fighting means I haven't walked away. Fighting means I still have skin in the game.

But oh, my sweet Lord, is it ever exhausting.

I keep my friend's cartoon on my desk and look at it every day. Most of the time, it makes me laugh. But sometimes, I gaze at that furious little girl, so determined, so mad, and I wish she'd allow herself a breather. I wish she'd drop her fists, unclench her teeth, and touch the ground. I wish the man, instead of fending her off, would take her hands in his and say, "Good, but that's enough for now. Let's go get ice cream."

What my grandmother knew — and I still don't — is how to make God my home. How to sit in his Presence gently. Quietly. Without a fight. Though there was nothing easy about my grandmother's life — she suffered poverty, illness, even the death of a child — she found a way to inhabit a consoling faith. She was certain of her God.

I'm not. But I would like to be. Regardless of what religious tradition or expression I choose — they're only containers, after all. Vessels for the holy — I'd like to learn how to make God my refuge, my solace, my safe place. Right now he is still too much my opponent, the stranger I grab in the night and lock in tiresome combat. My posture towards him is still the greedy child's. "Bless me!" Answer me. Fix me. Give me. I won't relax until you do.

My daughter's illness has taken me to a menacing land, and mine is not yet the posture of one who has traveled far and found her way home. My God isn't yet the one who holds a candle in the darkness, promising welcome. But every Christian tradition I know of extends the invitation in one way or another. Why can't I trust it? What will it take for me to hear and obey the voice of my God? "Come in. Sit down. Be with me. You're safe now. I love you. You're home."

Image credits: (1, 2) Debie Thomas.