Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

This past January 17th, those of us in the United States celebrated our annual remembrance of the civil rights leadership and advocacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. As grateful as I am for a day devoted to such a worthy memorial, it always sits a bit uneasily with me as I read the social media streams trotting out all the greatest hits of King’s speaking career. Memorials and holidays (having long ceased to be holy days, their etymological root) tend to take on a very superficial veneer in this country, with lots of perfunctory formal acknowledgments even by those opposed in action to the very ideals that King stood for.

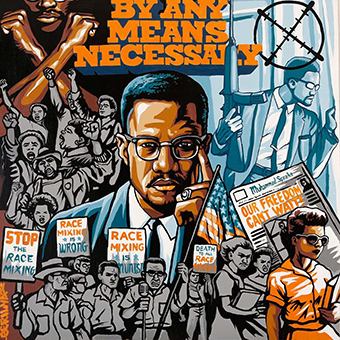

King’s place in history strikes at the very heart of our conception of a political community, though perhaps not in the way most people assume. Generally, when people think of King’s life and work, they think of his fight against segregation, his commitment to the tools of nonviolence, and his clarion call that America live up to her ideals. We focus less on his engagement and conflict with Malcolm X and the black nationalist movement (for context, see Dan Clendenin's review of Manning Marble's biography of Malcolm). Far from being a footnote to King’s story, the interaction between those two leaders of oppressed black communities raises the central issue of the human political story.

|

|

Mural on King St, Newtown in Sydney, Australia.

|

In Western political philosophy, there is perhaps a no more esteemed advocate for liberal democracy than John Rawls, whose writings on liberalism have provided a backbone for questions about justice, pluralism, rights, and equality. Yet despite the brilliance of Rawls’ writing, at its heart it misses the fundamental question that Martin Luther King and Malcolm X grappled with.

Rawls states in his book Political Liberalism that liberal political theory assumes that people have to live together despite their mutually incompatible worldviews. In his foundational thought experiment, no one is allowed to enter or leave society. With migration no longer an option, the conditions are set to articulate a space of possibilities that will allow a pluralistic society to persist in a state of relative peace. It all sounds rather rosy; after all, isn’t that the condition of our world, that we all have to make due together?

Well ... yes and no. Certainly most of us cannot afford to live apart from some community or other. But what Rawls overlooks is that there is a big difference between assuming that humans have to live together, and assuming that these humans have to live together with those humans. That was precisely the question that animated King and Malcolm. King believed in integration, in learning how to live in equality through love with (eventually) former white oppressors. Malcolm was a separatist, who believed that there could never be integration, insisting that black folk form a nation of their own with military and police strength to keep out white power. Neither man was motivated by the old (white) liberal belief that people left a “state of nature” to live together because it was mutually advantageous! For Malcolm, there was no advantage to having white neighbors, only suffering, while King believed that neighborly love with white people would be God’s redemptive act in America for the sin of its racism.

In the late 1950's, it was not obvious which of these two visions would win out, or even which should win out. It’s here I want to refer my readers to a truly marvelous book. James Cone has been widely and rightly celebrated for his books A Black Theology of Liberation and The Cross and the Lynching Tree. But I want to draw attention to a lesser known book of his, published in 1992, which for me is the most important book Cone wrote. It’s a lengthy tome entitled, Martin & Malcolm & America. In it, Cone lays out with wonderful rigor and accessibility the political and theological visions these two leaders had, and he juxtaposes their ideas in precisely the places where they speak to and contrast with each other. He makes an impressive attempt to understand the roots of their diverging visions, and does not shy away from criticizing where they fell short.

|

|

"X for Malcolm X" painting by the Filipino artist collective Gerilya in 2017.

|

At the heart of the book he draws a contrast between their two most well-known metaphors: King’s dream of an integrated America rooted in “beloved community” and living out her constitutional ideals, and Malcolm’s nightmare of black bodies being forced to integrate with the white folk who remain a source of terror and abuse.

Malcolm’s nightmare was motivated by life in the urban North, where he experienced the harsh reality that life for blacks in the supposedly tolerant northeastern U. S. was hardly any better than life in the Jim Crow south. Though whites in the North preached equality, they had little interest in actually sharing neighborhoods and office cubicles with black folk, leaving hundreds of thousands of blacks confined to poverty in dedicated ghettos. As James Cone describes the situation, “Ghetto existence [in the North] was defined primarily by unemployment and underemployment, dirty streets and overcrowded, rat-infested tenements, pimps and prostitutes, drug pushers and dope addicts, black-on-black crime, and police brutality.” Witnessing the "free" North, Malcolm experienced little reason to hope for anything better than a nightmare from integration with whites.

By contrast, King’s dream for a new America was rooted not in the world he saw immediately around him, but the world he could see from “the mountaintop,” to quote his favorite allusion to Exodus 34 where Moses surveys the Promised Land from afar. King had seen two visions, the first being the vision of human society implied in the U. S. Declaration of Independence that all people are created equal, and the second being the kingdom of heaven described in the Bible where ethnic identity and skin color no longer matter, for all are one in Christ Jesus. Thus he knew that the only world worth living in was a world rooted in justice and love, where justice is a condition for love. For King, desegregation or separation were not enough. Humanity will never reach the Promised Land unless we take the risk of faith and integrate, becoming the beloved community where all people live together in bonds of love defined by God’s indiscriminate love for all things.

We must be careful that we do not think King was the only one motivated primarily by theological vision. Malcolm X was passionately committed for a time to Black Islam, a separatist movement seeking to organize the African diaspora into an autonomous nation, with an eschatological hope of future divine retribution against whites that would restore the whole Earth to its properly black residents. Where King was motivated by his faith in Christ to call upon the moral conscience of those outside the black community for the sake of the black community, Malcolm was driven by his obedience to Allah understood through Elijah Muhammad to empower black communities in throwing off white power and claiming their heritage. Each man was operating with distinct theological visions, and it’s worth noting that “Malcolm’s verbal skill and public visibility forced King to take notice of him and develop his perspective on the American dream not only in opposition to white supremacists in the South, but also against persons whom he initially referred to as black supremacists in the North.”

|

|

The late Rev. Dr. James Cone, gone to be with Christ April, 2018.

|

Cone’s book is masterful, and essential reading to understand that the political question between these two men truly is ultimate: why should these particular people live together? It is a question put to people on all sides, oppressors and oppressed. Malcolm answered it one way, by saying, “We shouldn’t,” and with his answer comes the destabilization of the liberal democratic system that Rawls and so many others hoped to uphold.

King offered a different alternative to liberalism. King believed that revenge and retribution could bring no better future than the present suffering black folk already endure. In contrast to the tenets of Black Islam, he contended that the love of God displayed in Christ on the cross was a sacrifice to “destroy the dividing walls of hostility” (Eph. 2.14) between all people. The God revealed in Christ is powerful enough to change any heart and nation. “Martin was optimistic that his dream of a beloved community of blacks and whites, working together for the good of all, could be realized even in the most racist states in the nation,” writes Cone.

There is no logical analysis or set of universal principles by which to decide this question in favor of Malcolm or King. For it is a truly existential question, focused on what kind of community we will choose to become. What we choose depends on which vision captivates us more, and whether or not we have the moral courage to live it out.

Society as it exists today in no way reflects the liberal fantasy of autonomous individuals coming together in their freedom to form a social contract according to rational rules and mutual exchange. Black bodies were brought to this land bound in iron shackles and chains. There was no freedom in the choice of neighbors. The question now is whether we can be neighbors against the backdrop of such history. If Christians have a place in racial reconciliation, we might start where King started, by asking ourselves not which political party or social justice movement we will side with, but rather, what the Gospel has to do with all of this. Does the Gospel offer its own eschatological vision of justice, or are we condemned to liberal fantasy or vengeful longing?

Malcolm or King. The choice is all of ours.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Flickr.com; (2) Tumblr.com; and (3) Wikipedia.org.