Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

In the midst of the sandy dust of the Iraqi desert, some Muslims taught an 18-year old Christian how to pray. Fresh out of basic training and working as a chaplain’s assistant, I deployed in 2004 to a military-occupied base northeast of Baghdad along the Tigris river. At the time, I was serving as a “local national” escort (LNE), a military liaison supervising Iraqi contractors coming onto the base to provide infrastructure support. Given my official occupation, I was the LNE for the team building what would become the base chapel. Being a Christian teenager working with Muslim men on a Christian worship facility in their country was definitely a ... clarifying experience!

On my first day supervising the workers, I heard the dhuhr call to prayer echo from the nearby minaret. One of the workers nearest me walked over and asked if they could have a bottle of water and borrow one of the empty sandbags lying in a pile nearby. Perplexed, I gave my consent if nothing else out of curiosity. He walked a short distance away, placed the sandbag on the ground, and began to pour water over his head, hands, and feet. Once finished, he knelt on the sandbag and began to pray facing Mecca, using this coarse military-issue sack as a makeshift prayer rug.

|

|

A Muslim woman responds to the call to prayer in the desert.

|

My upbringing only introduced me to one religious practice prior to joining the military: my own. When I was going through the academy to become a chaplain’s assistant, I visited all the military-sponsored worship services on the base, marveling at the different expressions of Christianity, Judaism, and more. My background was non-denominational evangelical, which meant I grew up in a church where the worship was fairly informal and unstructured. This was particularly true of prayers: although we had a corporate time of prayer during Sunday worship, it was still very extemporaneous and disembodied, requiring little more of us than that we close our eyes, bow our heads, and dutifully listen. The idea that one had to prepare for prayer, with a ritual of selecting prayer rugs and washing one’s extremities, was quite foreign.

My experience with extemporaneous prayer made the next sequence even more astonishing to my young mind. The Iraqi man started standing, and began crossing his arms over his body, followed by profound bows before standing again. Prayer for me had always been something one says, not something one does—seeing prayer enacted with the body captivated my imagination. I could overhear some parts of his prayers, even understanding them thanks to a basic working knowledge of Arabic. I noticed that many of the phrases were repeated, and that at least part of his prayers followed a script.

Scripted prayers were often discouraged in my youth, out of the belief that this made praying insincere. Yet as I watched him stand and bow and proclaim in the hot desert wind, I realized I had never seen a more authentic prayer in my life. This ritual occurred again with the afternoon call to prayer. As I escorted off-base the last of the workers, I found myself wishing that Christianity had structured prayers throughout the day, with bodily motions and shared words.

The irony is quite humorous of course. Christianity in the West has a centuries-old history of praying the Hours. These prayers are designed for set times of the day, and have liturgies associated with them developed across generations of faithful believers. In my own Anglican tradition, we have the Book of Common Prayer, with its morning and evening prayer, an attempt by Thomas Cranmer to make praying the Hours available for all Christians. But my religious education growing up did not teach me any of this about my own Christian faith. In many ways, my journey into the Episcopal Church began in that war-torn desert, when I saw a Muslim man pray and realized I had never prayed with such sincerity in the fullness of my body.

|

|

The monks of Pluscarden Abbey pray the Hours.

|

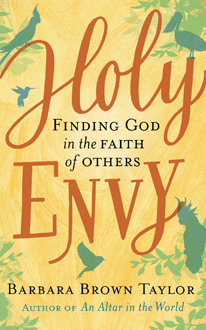

My experience was what Barbara Brown Taylor calls “holy envy.” Far different than the familiar vice, holy envy is the edifying experience of learning from someone of a different tradition a practice that you desire in your own life to bring you closer to the Divine Being. Although my contractor was a Muslim, here he was getting close to God in a way I never had, and wanted to. Barbara Brown Taylor uses the notion of holy envy as a teaching tool to encourage Americans to learn more about religious traditions other than their own. Her aim in the book is most laudable; my youth is a living witness to the poverty of religious education in the United States. In a liberalizing zeal to protect students from school prayer and the pledge of allegiance, primary education has veered to the opposite extreme forbidding all mention of religion.

Barbara Brown Taylor’s conviction that holy envy can help correct this situation is quite right. In my experience holy envy helped me overcome the poverty in my education about my own faith tradition. Having been raised Christian, the holy envy I experienced amongst my Muslim friends in Iraq sowed seeds that sprouted years later when I discovered a more catholic conception of Christianity, one that taught me about the rich liturgical history of the Church, the sacraments, the embodied worship of standing and kneeling and prostration, the use of set prayers and historic rituals. My first ever Anglican worship service was as foreign to me as the Iraqi man’s prayers, but I knew by the end of the service that I was home.

Much suspicion of other religions comes from a place of fear. Fear that there might indeed be truth in the worship of others (because that might imply untruth in our own worship). Fear that we might have to change our own assumptions about the nature of God. Holy envy is driven not by a fear of the unknown, but a love of truth. If we love the truth, we won’t be afraid to have our perspectives shifted and changed. When we act from a spirit of fear, it signals that we care more about maintaining our way of seeing the world than actually seeing the world.

Nonetheless, a love of truth does mean respecting the differences in our religious traditions. As Barbara Brown Taylor notes in her opening chapter of Holy Envy, religions are not all alike, and many faith traditions do conceive of the world in incompatible terms. For example, some strands of Buddhism teach that the way of wholeness lies in the renunciation of desire. Since unfilled desire is the source of so much suffering, renouncing one’s desires is the only way to be free of such suffering. By contrast, most streams of Christian thought teach that desire is part of the Creator’s good creation, and that what is needed for wholeness is not the renunciation of desire, but the redemption of desire. Through faith in Jesus Christ, we are remade into new people, not a people without desire, but a people whose desires pulsate with the very lifeblood of the Holy Spirit.

|

|

Holy Envy by Barbara Brown Taylor.

|

Holy envy helps us become more authentically people of truth, desiring to see the truth of the eternal Thou that lays claim to our lives. Truth means some ideas about God need to be discarded, while others need to be discovered. Barbara Brown Taylor, for all the wealth of insight in her book, seems to struggle with the place of truth in holy envy. At one point she endorses John Hick’s metaphor that Christianity is just one planet of religions in orbit around the divine Sun. Her epilogue suggests that she found a parish to call home in part because it felt like home, not because their practice of Christianity was more truthful. When promoting the book, Barbara Brown Taylor gave an interview on NPR in which she answered the question, “Why stay a Christian?,” this way:

“At my age, because it's the way I know best. I have learned the stories. I know how to look up Hebrew and Greek. I have practiced this tradition long enough to know how many ways it can go south, and to become somewhat wiser about my own ego, needs and theological questions. To switch ships now for me would be to go back to first grade and I don't have time to do that. But, in terms of why choose one? I can't honestly tell you that it's because I've compared and chosen. That's not true. This is the tradition I found myself in, and it's the one I know. It's the horse I'm on, Terry!”

I find this answer deeply unsatisfying. If the only reason to practice what we practice is because “it’s what we know,” then perhaps what we really need is to figure out whether there is anything in our practice that would cause others to experience holy envy. If our tradition has nothing worth envying, then maybe it’s not worth practicing. I prefer the older Barbara Brown Taylor, who in an homily titled “To whom can we go?” gave a brutal survey of some of the most offensive passages in scripture, without watering them down or explaining them away. After such a laundry list of disquieting stories, why be a Christian at all? Barbara draws attention to the disciples feeling the same way about some of Jesus' teachings. But she then notes St. Peter’s answer: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.”

Being Christian is not enviable if our tradition exists simply because that’s how we were raised, or because we benefit from a cultural privilege our religion now enjoys. It’s not enviable if it’s “what works for us.” My experience of my Muslim friends made me want to be a better Christian, not because it was what I had always known, but because they helped me see I had never really known it. When I came to know it better, I remained in this tradition because it is here, in this Christ, in these sacraments, in these scriptures, that we find the words of eternal life. To whom shall we go?

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Amazon Web Services; (2) Squarespace.com; and (3) INFORUM.