Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

On a rather secular university campus, the religious students tend to gravitate towards each other, even when we hail from different traditions. Though I worship in the Anglican tradition, I’ve had the joy of communing with many of my sisters and brothers in the Roman Catholic fellowship, learning from them and praying with them.

One of my more memorable experiences came one day when a student in the Roman Catholic fellowship sought me out, fighting back tears. I asked what was wrong, and she told me earlier that day she had been in a religious studies class with a professor who offered a “debunking” of the “Jesus resurrection myth,” suggesting a more psychological alternative. Discomforted by the professor’s theory, she sought out one of Christian pastors assigned to the university church. After explaining her experience, she asked them, “Can you help remind me what reasons we have for believing in the resurrection from the dead?”

To her surprise, the pastor responded, “To be honest, I don’t spend much time worrying about the reality of the resurrection. I just try to focus on what gives me life day to day. That’s where I experience resurrection.”

|

|

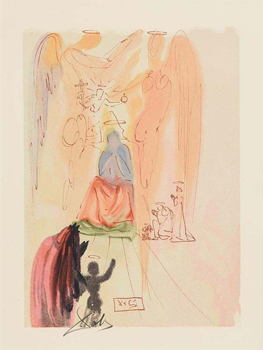

Opposition - Canto 11 Paradiso, The Divine Comedy

by Salvador Dalí |

After this conversation the student sought me out, parched for a reason to hold on to her faith in Jesus’ resurrection from the dead and the creedal hope for the future resurrection. “Doesn’t anyone believe any more?” she asked through profound emotion. Far from seeking some cheap apologetic to affirm her confirmation biases, my friend was agonized by an existential, not intellectual struggle. What had threatened her that day was the loss of hope. Not just hope in the Christian promise, but that other people are working together towards the same hope.

In a world of skepticism encompassing religion, politics, vaccines, climate science, and even our shared moral values, she wanted a community that would help her believe in something more. Both her professor and the campus pastor had offered “metaphors of resurrection” that were intended to provide something more believable. But to her heart, this felt like an admission that the hope we all really need isn’t real.

The Easter season is all about celebrating God’s love for us displayed through Jesus’ victorious resurrection from the dead, the “firstfruits” of the resurrection that is promised to us all (1 Cor. 15.23). Reflecting on my own life, I worry too often this celebration has a hollowness to it. Resurrection sounds wonderful, but feels far off and without any clear relation to the here and now.

In a recent essay for The Atlantic, Tim Keller has described how his diagnosis with cancer transformed his ideas about dying from a distant idea to a reality felt in the heart. Suddenly, belief in resurrection didn’t seem like some far off notion, for without it his cancer really will have the last word. Keller writes, “Theoretical ideas about God’s love and the future resurrection had to become life-gripping truths, or be discarded as useless.” Too often debates about what we believe as Christians concern stale formula which have lost their concrete practicality. By re-centering our questions on hope, we have a chance to transcend the old binary of belief and action, for hope is a belief that shapes our action, an act of faith that orients our believing.

What might the “more” be that my friend was looking for in the resurrection? What are we hoping for? I want to explore whether the path of listening might provide a better road to finding the hope of the resurrection. The Gospel of Jesus, of which the resurrection is a part, is supposed to be Good News—but for whom? For those who need it. Listening to how people respond to our beliefs as Christians might provide clues to the hope they are looking for.

A rather remarkable exchange took place a couple years ago between the New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof and Serene Jones, the current president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Kristof, a non-Christian who has expressed admiration for the teachings of Jesus, opened the conversation with a poignant question: “Do you think of Easter as a literal flesh-and-blood resurrection? I have problems with that.”

|

|

St. James of Hope - Canto 25 Paradiso, The Divine Comedy

by Salvador Dalí |

To his evident surprise, Serene Jones replied, “When you look in the Gospels, the stories are all over the place. There’s no resurrection story in Mark, just an empty tomb. Those who claim to know whether or not it happened are kidding themselves. But that empty tomb symbolizes that the ultimate love in our lives cannot be crucified and killed. For me it’s impossible to tell the story of Easter without also telling the story of the cross. The crucifixion is a first-century lynching. It couldn’t be more pertinent to our world today.”

Kristof, unpersuaded by the idea of the empty tomb as a symbol, followed up by pressing his original question: “But without a physical resurrection, isn’t there a risk that we are left with just the crucifixion?”

Jones doubled down in her response, “. . . what happens on Easter is the triumph of love in the midst of suffering. Isn’t that reason for hope?”

Now she presented him with a question, and all eyes should be on Kristof’s reaction. If we really care whether our Good News is a reason for hope, then we should listen to whether those we’re sharing this Good News with find hope in it.

Kristof replied: “Isn’t a Christianity without a physical resurrection less powerful and awesome? When the message is about love, that’s less religion, more philosophy.”

Unfortunately, Jones didn’t seem to notice that the hope she offered wasn’t being heard as Good News. In her final response, she insisted, “For me, the message of Easter is that love is stronger than life or death. That’s a much more awesome claim than that they put Jesus in the tomb and three days later he wasn’t there.”

Serene Jones’ response is very similar to the message my Roman Catholic friend received. Predictably, all manner of indignant emails and letters exploded in an uproar over her interview. Whatever else we make of Jones’ theological proposals, to respond with anything less than Christian charity is to display precisely the kind of “wobbly faith” she decries elsewhere in the interview. I found myself deeply saddened by the unkindness and insecurity her honest reflections produced.

|

|

Triumph of Christ and the Virgin - Canto 23 Paradiso, The Divine Comedy

by Salvador Dalí |

If there are reasons to be dissatisfied with Jones’ comments, I doubt they lie where her hate mail suggested. What was missing, above all, was deep listening. Jones was too preoccupied in the interview fencing with imagined fundamentalists to notice how her words were being received by the person right in front of her. Someone outside the faith was looking for “the more” in the resurrection. He had doubts about Jesus physically rising from the dead, and her alternative “triumph of love in the midst of suffering” offered him only platitudes and abstractions. What many of us really want to know is not whether love (in the abstract) can triumph over suffering (in the abstract), but whether there is someone who loves me in the here and now that can triumph over my suffering. To put it another way, did God do something after Jesus died on the cross that gives us reasons today to believe that God will do something for us too?

Despite the goodness of Jones’ intentions, the substance of her remarks divorce the hope of Easter from the divine action that produces it. Even if the resurrection remains a mystery we cannot fully comprehend or agree on the details, it is the conviction that God has triumphed in Jesus that assures us God can triumph in us. My friend was indeed looking to hold on to the hope that love will triumph in her life—but not as a warm feeling stemming from an incontestable aphorism, but as a saving act by the God who saves. We can believe that love triumphs because love already has. Jesus was dead and now he is risen, risen indeed! The same God who raised this Jesus from the dead will give life to our mortal bodies and our sin-broken souls.

Kristof was looking for a belief in the resurrection that is powerful and awesome. My friend was looking to hold onto her belief that had given her so much hope. In a media-saturated world of fake news and alternative facts, the temptation is strong to find the resurrection too much to ask and fall back on believing we should all just love each other. But when we look around the world, we see that “all you need is love,” to quote a classic Beatles song, hasn’t taken us very far in ending bigotry and brokenness in human life. If we’re to hope that the future will bring something other than humanity’s self-destruction, it needs to be a hope that saves us from ourselves. We need a hope that is not merely an abstraction about love, because abstractions cannot love us back or act for us. We need a hope that someone will always love us, even when we’re unlovely; and that this someone who always loves us will risk everything, even the cross, to bring us “life and life to the full” (John 10.10).

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Kunstveiling.nl; (2) Besoindart.fr; and (3) Morgan O'Driscoll.