Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

In a land mangled by perpetual civil war, a holy day can provide a rare respite from fear and fleeing. The last day of this past November was the festival of Tsion Maryam for the Tigray region of Ethiopia. Centered around an Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo parish that is believed by the locals to house the biblical ark of the covenant, the festival brings Ethiopian Orthodox Christians to places of worship all over the region in thanksgiving for God bringing the ark to their land.

This time, however, it wasn’t merely religious ritual that brought the worshipers together. They were also fleeing the fighting that has erupted in the last few months as the Tigrayan government found itself in renewed conflict with the Ethiopian federal government. Long a contested region in the aftermath of a boundary dispute between Ethiopia and their former allies to the north, Eritrea, the Ethiopian government accused the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) of re-opening military hostilities, a claim the TPLF denies. Tragically, the Ethiopian government response has been swift and unforgiving, destabilizing the region to produce what the UN has called one of the worst refugee crises in recent decades.

|

|

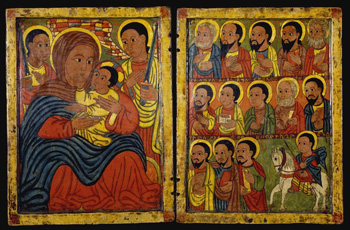

Diptych with Mary and Her Son Flanked by Archangels, Apostles and a Saint, Ethiopia, 15th century.

|

Hundreds gathered in local parishes and monasteries for Tsion Maryam to pray, seek shelter, and celebrate God’s great miracles. These included whole families, their elderly, their children, and the priests who celebrated the mass with them. In the midst of worship, soldiers descended on the area and began assaulting these holy places, chasing the people from the churches back to their villages, where they conducted door-to-door executions. The number of people killed, and the guilt of those who carried out the executions, remains uncertain, as all three governments have continued to shift responsibility in successive months.

Reading these news reports with horror from California where I live, where I can worship at whatever house of God I choose without fear of violence or death, I find God pressing the question on my heart, “What is the mission of the Church in a context like the Tigray?” These days, it’s too simplistic to simply read off Jesus’ command in Matthew 28.19-20, “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” Of course the mission of the Church is to preach the Gospel and make space for all people to worship the living God through Word and Sacrament; this still leaves unanswered how we can live this mission in contexts like the Tigray where the mere decision to remain in an area at all may mean certain death.

Two recent essays from other contexts have sharpened for me both the question and its possibilities. Abiola Mbamalu, a South African female theologian writing about Nigeria, reflects on the mission of the Church in the context of Christian-Muslim relations in a nation torn asunder by conflict between the two religious communities. Until very recently, Muslim jihadists under the moniker Boko Haram engaged in systemic attacks against all perceived threats to “pure” Islam, including local Christian communities. Hope generated by the somewhat reduced violence of the past few years has been tempered by attacks from Fulani herders, radicalized by jihad teachings and catalyzed by significant socio-economic disadvantage, against often defenseless Christian farm villages.

The decades of conflict between these two communities leads Mbamalu to suggest that the Church’s mission in northern Nigeria cannot be to command dislocated and traumatized Christians to try and share the Gospel with their Muslim neighbors. Instead, the Church has to undertake actions for the sake of the whole nation that might give the region a chance at bringing the violence to an end, or as Micah 4.4 puts it, where “everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree, and no one will make them afraid.” To this end, Mbamalu recommends the Church in Nigeria recognize its unique, national position as one of the few remaining long-lasting cultural institutions. Persisting through changes in party control of the government, the Church makes possible a sustained vision for the future of Nigeria. Mbamalu sees the Church in a sacrificial role, serving the nation despite the violence that has been permitted against its members. The Church can be a lifeline to thousands of displaced people and victims, facilitating the restoration of educational facilities and the rebuilding of local villages. In so doing, it displays the Gospel mission of Christ not by its proclamation, but by its sacrifice, its willingness to use its cultural capital to help the communities of the nation heal, even those that have brought violence against Christians in the land.

|

|

August 3, Acrylic on Canvas by Myanmar artist Mor Mor.

|

The other essay is written by Naw Myatt Hsu Mon, a female theologian at Holy Cross Theological College in Myanmar. The southeast Asia country presents a powerful opportunity for Western citizens to reflect on the mission of the Church in a nation where Christianity is and has always been an overwhelming minority. Nearly 90% of the country practices some form of Buddhism. Christianity has been present in Myanmar for only 200 years or so, and when a communist coup d’état overthrew the government in the 1960's, the push for nationalization led the communist regime to expel all foreign missionary organizations. The Church in Myanmar persists entirely through indigenous faithfulness, often to the point of having to prove independence from foreign interference. Even then, these Christian communities are viewed with a worry that Christianity is a kind of “trojan horse” to disrupt Myanmar culture. As a consequence, churches in Myanmar have largely focused on remaining invisible and isolated, removing themselves from the political equation so as to not disrupt the peace.

Hsu Mon worries that this takes the Church too far in the opposite direction from what Mbamalu describes in Nigeria. Where the Nigerian churches have been all too exposed to political action and violence, the Myanmar churches have not created much meaningful impact on the future of their nation and people. Since 2010 began a process of introducing liberal freedoms into the country, Hsu Mon calls on the Myanmar churches to see this as an opportunity. “[S]ociety should be able to sense the love of God through the Church,” Hsu Mon writes. Achieving this requires the Church to be mindful of the fears their neighbors have of sectarian proselytizing and foreign interference, and instead present the Church as an instrument in society that exists not just to serve its own interests, but the flourishing of the whole society, irrespective of religious affiliation. Churches, for instance, can be the conscience of the state, advocating for all members of Myanmar society before the government. When people can see the work of the Church as one of gracious giving rather than self serving, trustful relationships become possible that can put down deep roots in the community.

What these stories suggest for me is that the mission of the Church cannot be monolithically conceived. Without taking anything away from Jesus’ command to evangelize and baptize the world, the work of evangelism and mission must reflect contextual nuances. The proclamation of God’s victory over sin and death might be restorative in one context, while incendiary in another. In one context the Gospel proclamation might lead to a greater peace, while in another it might inflame new violence and killing. This does not mean we obscure the Gospel or hide our beliefs as Christians, but it may mean finding new ways to embody and practice the Gospel so that our neighbors experience the outpouring of God’s saving grace for the world, rather than simply another sectarian warmonger.

|

|

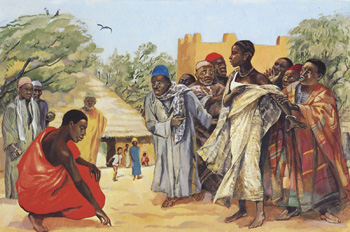

Indigenous art by Mafa Christians in North Cameroon, depicting John 8.1-11. |

Returning to the heart-breaking reports coming out of the Tigray in northern Ethiopia, I find myself reflecting on how for these Orthodox Tewahedo Christian communities, the mission of their churches might go no further than finding ways to protect each other from the power struggle in the region. They might just not have anything more to give than serving one another as Christ serves them; finding ways to worship while protecting their families; helping refugees find safe passage out of the region; tending the wounds of civilians maimed in the fighting; providing burial rites for their dead. Meanwhile those of us blessed to live in nations where sectarian war is not a daily reality ought to ask ourselves, How can we be the Church for these churches? How can we walk with them in prayer, in physical presence, or by helping to promote peace in the region, or providing sanctuary for refugees, or raising international visibility, so as to be in solidarity with them as fellow members of Christ’s Body?

Perhaps most importantly, what can we learn from them? What earnestness in worship might we discover from those who worship in the time of war? From those Christians in Nigeria who are literally loving the enemies who try to murder them? From Myanmar churches where Christianity has never held a privileged role or enjoyed special social protections? Theological speculation, on the Church’s mission or on any other part of the Christian faith, has never been impractical. All of these global communities confront the teachings of our faith in the most visceral, personal manner possible. In the shadow of the Adigrat sandstone, Tigrayan Christians face the all-too-practical hope of St. Paul’s proclamation that “we are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body” (2 Cor. 4.8-10).

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Smarthistory.org; (2) Facebook; and (3) Blogspot.com.