Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

I grew up in the State of Jefferson. No need to run to your map of the United States. You didn’t miss the announcement of another state admitted to the union. The State of Jefferson is not an actual state, though it once attempted to be. Today it exists more as a state of mind, a culture of independence and self-determination in a part of the pacific northwest that rarely becomes an object of national or international awareness.

More officially I am from Siskiyou county, growing up in a small town along the Klamath River that is part of a cluster of river communities extending from Interstate 5 all the way to the pacific coast. These minuscule villages are originally the native territory of the Karuk tribe, who are today headquartered in Happy Camp, where I went to high school. During the gold rush their land was swarmed with ambitious 49ers, and the creeks leading into the Klamath still bear the tell-tale upheaval of dredging tailings. The Karuk people over the past few decades have built a sustainable network of resources and a significant array of services supporting the wider community, living in uneasy alliance alongside the mostly poor white families who migrated to the area as a result of the mining influx. Outside of government jobs, work is scarce.

|

|

A Karuk elder woman in 2006 at a Karuk Tribal Reunion.

|

Lack of labor opportunities did not always beset life on the western Klamath River valleys. When we first moved to the area, there was a bustling logging industry, with multiple mills spread up and down the valley. Responsible harvest of a renewable resource is one of the best kinds of industries, and the mill in Happy Camp would provide high quality custom cut, kiln dried lumber. However, in the mid-90's the industry was largely halted in Siskiyou county due to failure of cooperation between several parties invested in the local forests. Historically, loggers and conservationists had worked closely to preserve and care for the forests that logging communities depended on for their livelihood. In the 80's, however, that relationship strained as national corporations moved into the area and began much more aggressively harvesting the old growth forests. This led to conservationist efforts to halt logging even if it meant damage to the timber industry. The International Woodworkers of America, a union of working-class loggers, abandoned their decades-old relationship with conservationists and allied themselves with their out-of-state corporate owners due to a fear that conservationists were seeking a zero-sum outcome between logging and environmental protections for animals like the spotted owl and the marbled murrelet.

Unfortunately for the local economy, both relationships became poisonous. Conservationists in the early 90's pursued vigorous lawsuits against the Department of Forestry, as most forests were federally managed, asking the Forestry to cancel planned timber sales. As conservationist efforts to curtail logging succeeded, out-of-state timber corporations like Stone Forest became less and less invested in defending logging rights in the state. By the mid-90's, Forest Service concessions to conservationists and corporate closures of local mills devastated the area. Hundreds of loggers and mill workers were unemployed. More significantly, most of the land in Siskiyou county is federally managed, meaning that the county cannot draw income for schools and public services from property taxes on the land. As a response, Siskiyou county had depended on kickback from timber receipts to fund public programs. When the timber industry collapsed, so did funding for local government. These narratives play an important role in understanding the fabled State of Jefferson.

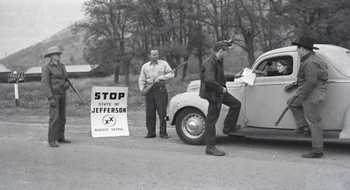

The State of Jefferson was a secessionist movement in the early 1940s by rural people in the northernmost counties of California, and the southernmost counties of Oregon, to secede from their respective states and form what would have then been the 49th state of the union (Hawaii and Alaska were not admitted until 1959). In November of 1941, a constitution was drawn for the new state, and armed militia began creating road blocks entering the geography demanding passerbys to recognize the new state. On December 4th, 1941, a local district attorney was inaugurated as governor of the State of Jefferson, with the state capital in Yreka, California.

|

|

Armed militia create blockades on November 27, 1941 demanding that drivers acknowledge the legitimacy of the State of Jefferson.

|

Those who know WWII history can see why this scheme did not succeed. The secessionists enjoyed media popularity, but three days later the media and national consciousness shifted to the global war when the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Nationalistic fervor overtook the nation, and the following day the government of Jefferson disbanded in an act of patriotic duty to support the national war effort.

But the “spirit” of the State of Jefferson continues, in the form of flags and the intended state seal emblazoned throughout the region, and calls for renewed efforts to secede or to oppose regulatory actions by the federal government. Much of this comes from a credible sense of lacking representation when state and federal actions are considered in the region. District 1 in Northern California notoriously leaves singular representatives responsible for hundreds of thousands of residents spread across nearly 28,000 square miles.

People press into their identity with the State of Jefferson because when they do experience interaction with their state or federal governments, the experience is frequently negative and impositional. They feel invaded, that major decisions about their natural resources are made without reasonable representation or negotiation. Jefferson provides a kind of fantasy, a hope to live in a state with a government that is local, with self-determination by the people who actually live in this area and make use of its natural resources.

This breakdown in the relationship between the national and the local results in at least two political consequences of significance for the Christian believer. The first is that the State of Jefferson mentality can promote a kind of political indifference to the wider national and global conversation. So few of the issues facing black communities in the midwest or the environmental impact of coal production on the east coast feel relevant in these isolated river towns. The rational incentive is for them to vote in their own interest, as their votes barely register at all. But this means they may be voting against the interest of those living in other parts of the state or the nation.

As Christians, this cannot be an acceptable political reality. Even if we feel our local concerns are not being heard, we have an obligation to consider and care for the needs of others beyond our community. St. Paul praises the church plants in Macedonia for their donations to the fund for vulnerable widows that St. Paul was collecting. “In the midst of a very severe trial, their overflowing joy and their extreme poverty welled up in rich generosity. For I testify that they gave as much as they were able, and even beyond their ability,” he effuses. “They gave themselves first of all to the Lord, and then by the will of God also to us” (2 Cor. 8.2-3,5). How we vote, how we interpret our political situation, must be conditioned to not only our own trials but also the trials of those who live far beyond our locality. More of the State of Jefferson needs to internalize the attitude of the original secessionists on December 8th, 1941, when they elected to end the movement in favor of the needs of the world at war.

|

|

This logo on a barn located on Interstate 5 between Grenada and Yreka was originally painted by my neighbor, Brian Helsaple.

|

At the same time, these tiny rural communities, made up almost entirely of poor whites, hispanics, and native Americans, have largely been forgotten by the wider community, with the State of Jefferson bearing witness to this perpetual distrust in state or federal institutions to listen to their concerns. People in the State of Jefferson have learned to live without dependence on the government, sometimes to the point of not paying taxes or even using public utilities. Those that do pay taxes see few benefits returning to their local community. As Christians, God calls us to follow God’s “love for the world” (John 3.16) by our own love for all. Government should not exist for the flourishing of the ruling party, or the wealthier municipalities, or the more populous counties, or the corporate elite. Government should serve all people while listening to all people.

I’ve told the story of the State of Jefferson because its lessons apply across communities. As Christians we should call the politically isolated and disillusioned to a wider consciousness, that they too have a place in state and national conversation. But we should also call on the human institutions of this world to remember those who have been forgotten, and to set aside partisan interests in favor of the flourishing of all. The relationship between the national and the local needs to be two-way, with local communities caring about their neighbors beyond the horizon, and state and national governments caring for those within their borders who are easily forgotten or ignored. Only in this way can we begin to show the same compassion Jesus displayed, who attended to the forgotten and ignored in every city he went to, but who refused to care only for those in his locality, choosing instead to give his life for the salvation of all humankind.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Media1.fdncms.com; (2) Politico.com; and (3) Wikimedia.org.