Lately I've been reminiscing that it will be thirty-five years ago this spring when in 1985 I finished my dissertation on the French sociologist Jacques Ellul (1912–1994). Two years later, in April of 1987, I interviewed Ellul in his home in Bordeaux with the translation help of my friend Jack Robinson. I still have the cassette tape (!) of our conversation, along with many fond memories.

Ellul was a member of the French Resistance. In 2001 he was honored by Yad Vashem with the title Righteous Among the Nations for his efforts to save Jews from the Holocaust. After the war he served as the Deputy Mayor of Bordeaux, and then for most of his life as professor of the history of law at the University of Bordeaux, and professor of social history at the affiliated Institute of Political Studies (1946–80).

Ellul was also an adult convert to Protestant Christianity in a country that is otherwise Catholic and secular. On August 10, 1930, God appeared to him in a "very brutal and very sudden" vision that forever after he refused to discuss. This conversion led to a carefully designed intellectual program for the rest of his life.

About half of Ellul's sixty books explore distinctly Christian themes like Jonah, Revelation, 1–2 Kings, hope, prayer, and ethics. The other half of his corpus studied what he considered were the driving forces of society, in particular technology, politics, and propaganda. He intended these two tracks of inquiry to inform and interact with each other in what he called a dialectical tension.

|

|

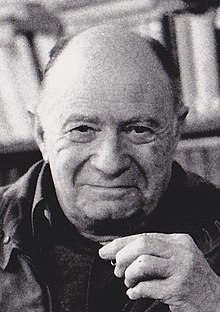

Jacques Ellul.

|

Ellul and his wife Yvette also started a church in their own home for blue collar workers. He worked with street gangs in the 1950s, was active in the environmental movement, took his students on hiking trips, and served on the National Council of the French Reformed Church.

In the unlikely chance that someone has heard of him, Ellul is best remembered for his trilogy of books that offered a counter-cultural analysis of technology. First came The Technological Society (1954), a book that Aldous Huxley promoted as one of the most insightful critiques of modern life. It has the provocative sub-title of "the wager of the century" (l’enjeu du siècle). That is, we have placed a bet on technology. Next came The Technological System (1977), and then The Technological Bluff (1988).

Whereas some people get bored with their dissertation, for me Ellul has been the gift that keeps giving. I think of him as a cultural prophet: a man before his time with his prescient critique of what he called technique. Perhaps it's because I have lived in the Silicon Valley for twenty-five years, but for my money, much of what Ellul wrote rings more true today than it did when he wrote it fifty years ago.

As early as 1940, Ellul argued that if Marx were alive today, he would would identify technology and not money or material inequity (Das Kapital) as the defining force in society. He insisted that we have little choice when it comes to technology because it imposes itself upon us. We are forced to adapt to it rather than vice versa. He argued that technology is a powerful means that is typically unconstrained by ethical ends. It permits little outside judgment, so that what can be done will be done.

Technology is also a totalizing system that encompasses every human activity, and outside of which nothing much matters. The non-technical person or activity is relegated to a second-class status on the periphery of power, prestige, and money (cf. the humanities). And most disturbing of all is how people uncritically view technology as the ultimate liberator. Evgeny Morozov has called this "the folly of technological solutionism." Ellul called it our new sacred, and woe to the person who would de-sacralize this powerful myth.

Gene Editing (CRISPR). Artificial Intelligence. Big Data. Global Surveillance. Driverless Cars. These are only five examples of the promise and perils of some of our most important technologies today. They also exemplify the characteristics of technology that Ellul articulated fifty years ago.

Technology has benefited the entire world in numerous ways. That's obvious. But there's also a consensus now among some of our elite technologists that there's a dark side to the digital world in general, and in particular to the behemoths like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple.

China has announced its intentions to surpass the United States in technology (especially AI) in the next thirty years. At three times the size of the United States, and because of its authoritarian government that can make unilateral decisions (and funding), some see China as an even bigger threat with its own four horsemen of technology: Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent (which has an office near my house), and Xiaomi. As Bernard-Henri Lévy observed, these techno-giants combine tyrannical power with sweet seduction to enslave us.

What can we do? Ellul made what might be the most important point. In the movie The Betrayal of Technology (1992) about his life and work, he challenges us to have "a radical discussion about our modern life" that is dominated by technology. "The question now is whether people are prepared or not to realize that they are dominated by technology. And to realize that technology oppresses them, forces them to undertake certain obligations and conditions them. Their freedom begins when they become conscious of these things."

In Part 2 of this essay that JWJ will post on February 2, I will do just that. In particular, I will explore three of the biggest and even terrifying challenges that we face in our new Techtopia. Stay tuned.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net