For Sunday April 17, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 10:34-43 or Isaiah 65:17-25

Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24

1 Corinthians 15:19-26 or Acts 10:34-43

John 20:1-18 or Luke 24:1-12

In our epistle this week, St. Paul makes a claim about Jesus’s resurrection that feels truer and truer to me, the older I get: “If Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain… If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.”

Amen.

I can’t speak for Paul, but I can say that Christ’s resurrection is the heart of my faith and the foundation of my hope. It is the reason why I’m a Christian. Without the empty tomb, without Jesus’s historic, bodily return to life two thousand years ago, I simply can’t reconcile God’s love and justice with the horrors I see in the world around me. Death is too appalling a violation. Evil is too ferocious an enemy. Injustice is too cruel and endemic a reality. Humanity, though beautiful, is broken beyond description. I need the empty tomb. I need the promise of resurrection.

That said, I struggle with doubt every single day. I even struggle with doubt on Easter Sunday. It’s not easy to affirm resurrection in a disenchanted world, a world that considers miracles embarrassing; disdains belief in an afterlife; mocks “crazy” things like angels, demons, prophets, and saviors; and shies away from mysteries that lie outside the purview of science. We live in such a world, and so we struggle to believe. Of course we do.

What comforts me is that the first witnesses to the empty tomb struggled, too. As our Gospel reading from St. John describes it, Jesus’s friends stumble around in the half-light on that third day after his crucifixion, running here and there in their confusion. Is it an angel, sitting in that unlit tomb? Are those shadows mere tricks-of-the-eyes, or are they grave clothes? That man lingering outside — is he really just the gardener?

“Early in the morning, while it was still dark…” That’s where Easter began two millennia ago. It’s where Easter still begins now. In the dark.

|

It helps me to remember that trumpets and choirs, vestments and lilies, processions and exclamations — all came later. Easter began with fear and bewilderment. As the shocking possibility of resurrection collided with the grim lies of injustice and empire, the first disciples had to reach out with their imaginations and grab hold of hope in mere slivers. They had to hope in the midst of their struggles. In the heart of the shadows.

Perhaps the Gospel accounts of the resurrection keep surviving our doubts because they ring so true to human nature. In John’s version, we see individual people having profoundly individual encounters with Christ. The encounters don’t look identical. When Peter sees the empty tomb, he runs away. When "the beloved disciple" sees it, he believes without comprehension. When Mary sees it, she weeps and waits for more. But all of them, without exception, experience Easter. The resurrection meets them where they are.

In other words, we come to the empty tomb as ourselves, for good or for ill. We don't shed our baggage ahead of time; it barges in with us and shapes our perceptions and conclusions. What matters, then, is encountering the risen Jesus in the particulars of our own lives. What matters is finding in the empty tomb the hope we need for our own struggles, losses, traumas, and disappointments. Whatever universal claims we make as Christians must begin in the rich, fertile ground of our own hearts, our own stories. Whatever acclamations we cry out on Easter Sunday must begin with a willingness to linger in the garden, desolate and alone, listening for the sounds of our own names, spoken back to us in love. For our testimonies to ring true, they must originate in radical, intimate encounter. The question is not, “Why should other people believe?” but rather, “Why do you believe? Why is the resurrection of Jesus essential to you? What does Christ’s rising look like in your life?”

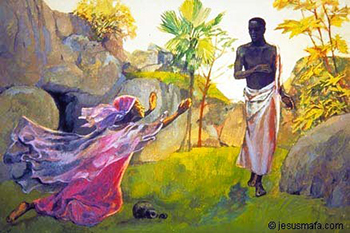

In John’s account, Mary Magdalene sees Jesus first because she chooses to remain in the holy darkness, bereft and bewildered. She doesn’t flee. She doesn’t sugarcoat her despair. She doesn’t go numb. She stays put in the place where her pain resides. She gives the grief, desolation, hopelessness, and agony of her circumstances their due. Unlike her male counterparts, Mary refuses to abandon what is real, even when what is real is unbearable. I love the way her story honors sorrow as a legitimate and faithful pathway to revelation.

|

In my own life, I find it increasingly true that clarity, hope, and healing come when I am willing to linger in hard and barren places, places where the usual platitudes fall flat, and all easy answers prove inadequate. Jesus reveals himself in the shadows, and sometimes it takes a long time to recognize him. He doesn’t look the way I expect him to look. He doesn’t let me cling to my old ideas of him. He disappears again just as I grab hold of him. But he comes, he calls my name, and in that instant, I recognize both myself and him.

And then there’s Peter. Peter who runs headlong into the tomb — and runs right back out again. Impatient, impetuous, headstrong Peter. He just can’t bear to stay in the wounded place. He flees instead.

I’m so grateful that his authentic response to the empty tomb is included in the Gospels. Why? Because we need the disciple who runs. We need to know that even when our doubts, questions, betrayals, and failures send us sprinting for the exit doors, the good news of Easter will find and claim us, anyway. Peter is too jittery to wait with Mary. Too proud, exhausted, or ashamed to weep in her presence. Too numb with despair to see the angels and hear their news.

Perhaps like you, I’ve been there. I’ve been in emotional landscapes so desolate, I’ve lost my ability to take in the Gospel. I’ve doubted Christianity so seriously, I’ve run to the point of near-collapse. I’ve missed a fair number of the “angels” God has sent my way, because I couldn’t remain still and hear them out. And yet. And yet the resurrection story has found and claimed me, anyway.

If you are a runner like Peter, if you act first and reflect later, if you go numb sometimes, if the good news bewilders you and sends you bolting for the doors — the Easter story is for you, too. It will always be for you. Run if you need to — it will wait for you.

Finally, there’s “the beloved disciple.” He enters the tomb after Peter, sees Jesus’s linen wrappings lying about, and believes without understanding. It’s not clear from the text what he believes, or how deeply. Does he believe that Jesus’s body has been stolen? Does he embrace the possibility that Jesus is alive? Does he recognize that God has vanquished death and vindicated the Messiah?

We don’t know. We only know that “he sees and believes.” Meaning, he leans into the truth of his experience, the evidence of his own eyes. He gives himself over, without cynicism or despair, to whatever messy faith is possible in the moment, and then he leaves the door open for his faith to deepen. He believes as he can, and trusts as he can. No more, no less.

I love the way the beloved disciple’s story honors the gap between faith and understanding, because it’s a gap I know so well. I believe but I don’t (yet) understand. I believe in the resurrection, but I don’t understand death’s ongoing cruelty. I believe that Jesus reigns, but I don’t understand the elusive nature of his kingdom. I believe that all things will be well, but I don’t understand why they’re not all well now.

|

Saint Anselm of Canterbury’s motto for the Christian life was “faith seeking understanding.” I like that. It invites me to begin right where I am. What have I experienced of Jesus so far? Can I hang onto the faith that is possible in light of my experience, incomplete though it is?

The remarkable thing about the resurrection is that it grows in us. It roots us, and it roots itself into us. Often, it’s only in retrospect, only as we look back at the “gravesides” of our lives, that we notice this rootedness, and find the miracle the first disciples found.

Poet R.S. Thomas describes the process this way in his poem, “The Answer”: There have been times/when, after long on my knees/ in a cold chancel, a stone has rolled/from my mind, and I have looked/in and seen the old questions lie/ folded and in a place/by themselves, like the piled/graveclothes of love’s risen body."

St. Paul sums up his teaching in this week’s epistle with a promise rooted in pure joy: “In fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died.” He is risen. He is risen indeed.

This lectionary essay is the last one I will post as a staff writer for Journey with Jesus. I’m grateful that it’s the essay for Easter Sunday, because the resurrection reminds me that our endings — however bittersweet — are not final. New life comes; it cannot be stopped. Every change, every sorrow, every hope, and every farewell we experience is held in the arms of the risen Christ. Like the first disciples, we might doubt, stumble, flee, and fall. But like the Christ of the empty tomb, we will also rise. This is the promise of resurrection.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) ecumenicus; (2) Rachel Held Evans; and (3) Godspace.