For Sunday December 13, 2015

Second Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Zephaniah 3:14-20

Isaiah 12:2-6

Philippians 4:4-7

Luke 3:7-18

The third Sunday of Advent is traditionally called “Gaudete” or “Rejoice” Sunday.” “Gaudete in Domino semper,” St. Paul writes in this week's lectionary. “Rejoice in the Lord always.”

In many churches, the penitential purple of the season is put aside this weekend, in favor of a lighter, happier rose. Most of the lectionary readings emphasize celebration, anticipation, and joy. “Sing aloud!" the prophet Zephaniah instructs us. "Rejoice and exult with all your heart!"

"Shout!" "Proclaim!" and "Sing for joy!" says the prophet Isaiah. “Give thanks to the Lord, call on his name, and make known his deeds among the nations.”

I don’t know about you, but I find these exhortations difficult. In part, the problem is linguistic. “Rejoice” and “exult” are churchy words — words I don’t hear in regular life — so I feel clumsy around them. “Joy” itself is a word so overused in America’s commercialization of Christmas, I find it opaque. As for "proclaiming," "shouting," or "singing aloud?" Not so much. I’m not a proclaimer; I’m shy, introverted, and happiest when I’m quiet. I don’t even know what shouting for joy would look like.

But the texts for this week present other challenges. “Gaudete” is the word’s imperative form; we are commanded to rejoice. Really? Even on my best days, I hate being told what to feel. Rejoice? Sing praises? Shout? “No!” my inner two-year-old screams, stomping her foot and crossing her arms. “I. will. NOT.”

And that’s on good days. What about bad days? How are we supposed to rejoice when our hearts are breaking? What songs of gladness should we sing when despair, exhaustion, or terror darkens our lives? Do these readings advocate pretense? Inauthenticity?

I don’t have satisfying answers to these questions, so I spent a lot of time this week brooding. Luckily, the lectionary didn’t leave me high and dry. Just as I was about to attempt a forced, anodyne essay on Advent Joy — BOOM. I delved into the Gospel reading. Cue John the Curmudgeonly Baptist, the bearded killjoy of Christmas.

|

|

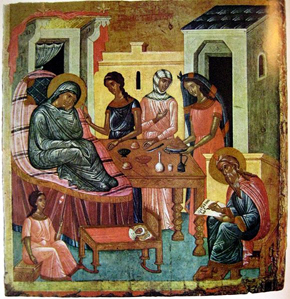

Birth of John the Baptist.

|

"You brood of vipers!" he shouts across the wilderness in the Gospel of Luke (clearly having skipped class the day his homiletics professor lectured on cuddly sermon openings.) "Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruits worthy of repentance."

How this austere reading made its way into the lectionary for Gaudete Sunday is beyond me, but I’m not complaining. No one has ever called me a viper before, and I have to confess: I'm curious. Maybe even relieved. At last! Hard words for hard lives. Nothing saccharine, nothing I might scrawl across a Hallmark card or stuff into a giftbox. “You brood of vipers!” Repent. Bear fruit. Wake UP.

According to St. Luke, great crowds streamed into the desert to get yelled at by John. Why? Why were they willing — no, eager — to hear his fire-and-brimstone preaching? What attracted them?

The first clue lies in the question they asked John at the conclusion of his sermon. "What should we do?" That's not a question people ask when things are going well. It's the question we ask when we've come to the ends of ourselves. When the received wisdom has failed, when our cherished defenses are down, when our lives are splitting at the seams. It's what we ask when we're weary, bored, disillusioned, or desperate. "What should we do?"

John's answer provides our second clue. Imagine him if you will — a wild beast of a man, ascetic and rough. Dressed in camel’s hair and fueled by locusts, his very appearance bespeaks the margins. What did the crowds think such a fringe character would say in answer to their question? Abandon your homes and families? Dwell in the desert? Reject your culture? Start a revolution?

Given John's demeanor, the crowds might very well have expected such radicalism. But the answer he gave them was even more radical — so radical we stand in danger of missing it: What should you do? You should go home.

Go home to your families, your neighbors, your vocations, your colleagues. Stop fleeing. Stop insisting that God is somewhere else, somewhere far away from the grit and sweat of your nights and days. Inhabit the stuff of your lives as deeply and as generously as you can; your Messiah is closer than you think. Inhabit your life, no matter how plain, how obscure, how unglamorous. Why? Because the holy ground that matters most is the ground beneath your feet.

Wait. Is that really what John said? It is. Think about it. To the tax collectors, he said, "Collect no more than the amount prescribed for you." To the mercenaries: "Don't extort money by threats or false accusations; be satisfied with your wages." To the Pharisees and Sadducees: "Don't allow your religious heritage to make you arrogant or complacent."

|

|

The Visitation: Elizabeth and Mary.

|

To everyone who had anything: "You have gifts to give. Yes, you do. YES, YOU DO. Share."

What John was daring to suggest to his listeners is that holiness is not the ethereal and mysterious thing we tend to make it. If we're willing to look closely, if we're willing to believe that nothing in our lives is too mundane or secular for God, then we'll understand that all the possibilities for salvation we need are embedded in the lives God has already given us. There is no "outside." We don't have to look "out there." The kingdom of heaven is here, within and among us.

Which means we have work to do — work so ordinary, it will almost definitely disappoint us. I wonder how those tax collectors felt the next time they headed out to collect money. Wait, God's kingdom is here? Here in this hated profession? Here among people who'd just as soon spit in my face as pay me what they owe me? God cares how I live here?

The Gospel writer called John's exhortation "good news." Well, it can be. If you've believed in your secret heart that your life — your family, your heritage, your vocation, your future — is outside the purview of God's saving goodness — then what John has to say is good news indeed. Your life is infinitely dear. Nothing in it is beyond redemption. Nothing.

On the other hand, if you long to flee, if the life you have is not the life you want or even want to want, then John's good news might feel like a stab to your soul. I won't lie — I come to this passage with ambivalence. I feel relief, but I also feel sorrow. Some days, I'm ready to inhabit my life in the ways John suggests. Some days, all I want to do is run.

There's no need to be surprised by this — God isn't. After all, we're in the desert now; we've left cheap cheer behind. This is joy for grown-ups.

John concludes his sermon in the wilderness with a harrowing description of the coming Messiah: "He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire."

Are you squirming yet? How is this good news, this portrait of a Jesus who judges, sorts, and burns us?

| |

|

Icon of John the Baptist.

|

I wonder if I squirm because I misconstrue the meaning of judgment. I tend to equate judgment with condemnation, but in fact, to judge something is to see it clearly — to know it as it truly is. In my dictionary, synonyms for judgment include discernment, acuity, sharpness, and perception.

What if John is saying that the Messiah who is coming really sees us? That he knows us at our very core? Maybe the winnowing fork is an instrument of deep love, patiently wielded by the One who discerns in us rich harvests still hidden by chaff. Maybe it's in offering God every particular of our lives that we give Him permission to "clear" us — to separate all that's destructive from all that is good, beautiful, and priceless.

I called John the Baptist a curmudgeon, but here's an ironic little fact: he is the patron saint of spiritual joy. He was still a fetus when he first leapt at the presence of Mary and Jesus. He rejoiced at the sound of his "bridegroom’s" voice. When it was time for him to “decrease” so that Jesus could “increase,” he did so willingly, saying, “My joy is now full.”

Clearly, John understood something hard and flinty about joy. Joy is not sentiment. Joy is not happiness. Joy will cost you. "Bear fruits worthy of repentance," John told the crowds who flocked to him in the Judean wilderness. Bear fruit — bring it forth. But also, bear it — carry it, shoulder it, endure it. Your life is a golden field, ripe for sacred fire. Yes, the fire will hurt, but the One who wields the flame is trustworthy. He knows you. He sees you. He will gather you. Gaudete.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.