From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, A Lament for the Vineyard (2020); Ron Hansen (novelist), The Vineyard (2017); Dan Clendenin, The Creation in Psalm 19 (2011); and David Gill, The Decalogue: Ten Words on Life, Love and Justice (2008).

For Sunday October 8, 2023

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 20:1–4, 7–9, 12–20 or Isaiah 5:1–7

Psalm 19 or Psalm 80:7–15

Philippians 3:4b–14

Matthew 21:33–46

This Week's Essay

The Old Testament reading this week brings us to the Ten Commandments. The Decalogue has understandably enjoyed pride of place for both Jews and Christians. I have listed them at the end of this essay.

Despite their privileged status, there's always been significant ambiguity about the role of the ancient Decalogue in our modern lives. Here are just three of many examples.

By one count there are 4,000 public displays of the Ten Commandments, including the Supreme Court itself (both outside and inside the building). Sometimes the Supreme Court has allowed the public display of the Ten Commandments, while other decisions have barred them.

Zeal for the commandments runs high, but so does ignorance. One poll indicated that 79% of Americans oppose the idea of removing displays of the Ten Commandments from government buildings, even though another survey indicated that fewer than 10% of Americans can identify more than four of the commandments.

Scripture itself can sound ambiguous about the law. The enemies of Jesus criticized him for breaking the law. He responded that he didn't come to abolish the least bit of the law but to fulfill all of it. In Romans and Galatians, Paul insists that Christ is "the end of the law." This week's epistle to the Philippians emphasizes this point. But Paul also said that "we do not set aside the law." So, does Christ as the "end" (telos) of the law mean its cessation or its fulfillment?

|

|

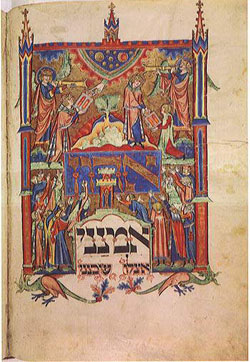

Moses receives the 10 commandments, Jewish prayer book, Germany, c. 1290.

|

There are four versions of the Ten Commandments — Exodus 20 and 34, Leviticus 19, and Deuteronomy 5. The first four commandments describe God's unique relationship with his covenant people — the prohibitions against polytheism and images, the sanctity of God's name, and the sabbath rest. The last six commands are more general, not unusual in ancient law codes, and they could apply to many diverse societies — parents, murder, adultery, kidnapping, perjury, and property.

In his book A Little History of Religion (Yale, 2016), Richard Holloway pays special attention to the first three commandments. They give us what he calls "the most important insight into God ever discovered by humans" — the prohibition against idolatry.

The second "word" reads, "you shall not make for yourself an idol." But a few pages later that's exactly what the people did: "Come, make us gods who will go before us" (Exodus 32:1). Before Moses ever descended Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments, the Hebrews grew impatient. They begged Aaron for a golden calf. They built an altar so they could bow down to their "gods of gold" (32:31). In this ancient story, so evocative with contemporary applications, the people worshiped a golden god, sacrificed to it, "indulged in revelry," and proclaimed national celebrations.

We've been creating our own gods in our own image ever since.

Idols lure us with powerful illusions and misplaced hopes. They make seductive promises. They promise much but deliver little. Our false gods come in all sizes and shapes. The advertising industry testifies to the power of our puny "household gods." We idolize anything and everything — career, race, gender, sex, health, wealth, age, and especially nation. Our personal gods are so petty and pathetic that they would be laughable if they weren't so insidious.

These household gods are child's play compared to our national idols. National idols are more global than personal, more public than private, and more institutional than individual. They unleash far more fury upon humanity than our little household gods.

|

|

Moses, Salvador Dali, 1975.

|

The most violent national idol is the War God. The sociologist C. Wright Mills used a suggestive description when he spoke of our American "military metaphysic," that is, our tendency to construe every national aspiration or international problem in distinctly military terms. In just the last hundred years, at least 200 million people all over the world, mainly civilians, have been sacrificed to the War God. Since 1775, America has been involved in over a hundred wars.

Our idolatrous impulse to create God in our own image, for our own purposes, is so strong and dangerous that the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968) called the gospel revelation the Aufhebung of all human religion — that is, its abolition, annulment, or invalidation.

That’s too extreme and conveniently binary for my taste. Not all human religiosity is inherently idolatrous. But Barth was repudiating Hitler, who claimed God's sanction, and his own seminary professors, who had signed on to Hitler’s genocidal program, so his warning is well taken — divine revelation and human religion are not the same thing.

And so the radical insight of Richard Holloway — the "real target" of the first three commandments against idolatry was religion itself: "And not just the kind that got people dancing around a golden calf. It was warning us that no religious system could capture or contain the mystery of God. Yet in history, that's exactly what many of them would go on to claim. The Second Commandment was an early warning that the organizations that claimed to speak for God would become God's greatest rivals, the most dangerous idol of them all."

And so the commandments against idolatry would save us from our besetting sin of breathtaking presumption: "You shall not misuse the name of the Lord."

To bestow a name, to use a name, or to know a name, says Michael Coogan in his book The Ten Commandments (Yale, 2014), is an "expression of control." When Adam and Eve named the animals in Genesis, they exerted "dominion" over them. When conquering nations subdued an enemy, they often changed their names as a sign of subjugation (cf. the book of Daniel).

Despite the casual confidence with which we speak and worship, control or dominion over the name of God is precisely what no person can have. Ever. The very thought is blasphemous. Coogan gives two examples.

|

|

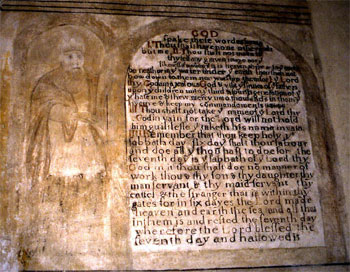

Moses and the 10 Commandments, 16th century church fresco.

|

When Jacob asks the divine messenger to tell him his name, the response is evasive, "Why do you ask my name?" Or again, when Manoah asks the angel of the Lord, "What is your name?" the reply is similar: "Why do you ask my name? It is beyond understanding." These two examples echo God's famously evasive response to Moses, who also asked about God's name: "I am who I am."

And so some Jews honor the mysterious, the inexpressible, and the inviolable name of "God" (YHWH) by not even pronouncing it. Instead, they substitute the word "adonay" or "Lord." Or sometimes you might hear an observant Jew refer to God as Hashem—"The Name." The Name that cannot be named.

The third commandment about abusing the name of God warns us not only about our casual presumptions. It also reminds us of the inherent limits of human language when we speak about the Wholly Other God. CS Lewis captured the practical implications of this in his Footnote to All Prayers (below). This isn't the last thing or only thing we could say about the ineffable Name of the infinite God, but it should be the first.

These limitations can be a liberation. I no longer have to pretend that I fully understand God. The mystery of prayer becomes something to honor rather than to explain. I don't even need to be right, for in his "magnetic mercy" God will "my limping metaphors translate."

Having honored the third commandment as best we can, we're prepared for the shocking words of Jesus — that the God of Mount Sinai is not only the Infinite Other. He's also my Intimate "Abba."

For further reflection:

1. You shall have no other gods before Yahweh.

2. You shall not make for yourself an idol.

3. You shall not misuse the name of the Lord your God.

4. Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy.

5. Honor your father and mother.

6. You shall not murder.

7. You shall not commit adultery.

8. You shall not steal.

9. You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor.

10. You shall not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor.

Weekly Prayer

C.S. Lewis

He whom I bow to only knows to whom I bow

When I attempt the ineffable Name, murmuring Thou,

And dream of Pheidian fancies and embrace in heart

Symbols (I know) which cannot be the thing Thou art.

Thus always, taken at their word, all prayers blaspheme

Worshiping with frail images a folk-lore dream,

And all men in their praying, self-deceived, address

The coinage of their own unquiet thoughts, unless

Thou in magnetic mercy to Thyself divert

Our arrows, aimed unskillfully, beyond desert;

And all men are idolaters, crying unheard

To a deaf idol, if Thou take them at their word.

Take not, O Lord, our literal sense. Lord, in thy great

Unbroken speech our limping metaphor translate.C.S. Lewis (1898–1963) was a Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Oxford and Cambridge universities. In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of his death, he was honored with a memorial stone in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, alongside Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Handel, Dickens, and many others.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Library of Congress; (2) PicassoMio; and (3) PaintedChurch.org.