From Our Archive

Lindsey Crittenden, Who Wants to Wait? (2007); Dan Clendenin, Dreams of a Christmas Credo (2010); and Betting on Salvation (2013); Debie Thomas, Into the Mess (2019).

For Sunday December 18, 2022

Fourth Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 7:10–16

Psalm 80:1–7, 17–19

Romans 1:1–7

Matthew 1:18–25

This Week's Essay

In his 2016 memoir Revelation, Dennis Covington "searches for faith in a violent religious world." His book makes for difficult reading, and yet I love how it deconstructs three of our perennial challenges at Christmas — capitalist consumerism, religious sentimentality, and despair for our world.

Covington channels Psalm 80 for this week, which begs God: "Come and save us. Restore us. You've fed us the bread of tears, and made us drink tears by the bowlful. Return to us. Look down on us. Revive us!"

The memoir explores Covington's journey in and out of faith, his family history, current events, his global travels, and the affirmations of faith that he finds in the people he meets — which is to say that he does what each one of us must do in our own search for an authentic faith in our violent world.

Covington travels to places of extremity and discovers faith not so much despite suffering and violence, but precisely in and because of the apparent absence of God's presence. He quotes Kayla Mueller, the American aid worker who was murdered by ISIS in 2015: "Some people find God in church, some people find God in nature, some people find God in love. I find God in suffering."

In Juárez, Mexico — by some measures the most violent city in the world, he participates in an annual burning of an effigy of Judas. He spends a week at a "lunatic asylum" out in the desert (Albergue Para Discapacitados).

|

|

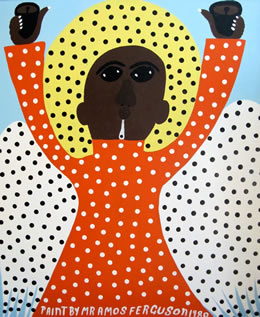

Angel.

|

He circles back to his youth in Birmingham, Alabama, during the civil rights years — his mother's cancer and nervous breakdown, his brother's life long mental illness, and his own alcoholism, bankruptcy, and psychiatric hospitalizations.

Most of Revelation describes Covington's experiences in the violent borderlands of Turkey and Syria, particularly in Antioch and Aleppo. There, he experiences the horrific sufferings of others, "a definition of faith as clear as any in the Gospel of Jesus Christ." Among those who have nothing, and who have experienced the worst of everything, he finds faith.

One distraught father, holding a decapitated little girl, implored Covington: "We bring our case before God, before God alone, for humanity has failed us."

That's what Psalm 80 does. It's what Covington does. And it's what we're all invited to do at Christmas.

We confess that "humanity has failed us" —

all of our false hopes for good news, our bitterly polemical and dysfunctional politics, our technophilia, our self-help schemes. We bring all the violence and suffering of our world, all of our personal brokenness, we lay it before God, and with the psalmist implore him: "Come and save us."

And then, in a sort of call-and-response that's separated by 1000 years, the gospel for this week responds to the cry of the psalmist: "He will save his people." (Matthew 1:21).

|

|

A Lady Expecting.

|

The story of Jesus reveals the face of God. It's a story not about sentimentality but about suffering. The first Jewish believers identified Jesus with the Suffering Servant in Isaiah. He was a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief. The Apostles' Creed confesses rather starkly that "he suffered and died."

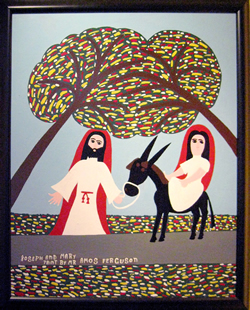

Jesus entered our world in weakness and vulnerability. A young mother gave birth in a barn, for Joseph and Mary were wandering and homeless when they were turned away at the inn. I love how Chesterton captures this in his poem The House of Christmas: "There fared a mother driven forth / Out of an inn to roam; / In the place where she was homeless / All men are at home... A Child in a foul stable, / Where the beasts feed and foam; / Only where He was homeless / Are you and I at home."

The aged Simeon then uttered a dark prophecy to the young mother that eventually found fulfillment in far worse ways than she ever could have imagined: "This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be spoken against."

Hunted by King Herod, the holy family fled to pagan Egypt where they found asylum. The political ironies in the flight to Egypt are remarkable. The infant Son of God fled as a displaced refugee to a foreign country, Egypt, Israel's sworn and symbolic enemy that had oppressed the Jews for 430 years. The place where Pharaoh had unleashed his own infanticide against the firstborn Israelite children became a refuge for Jesus.

Whereas the pagan magi of Persia worshiped the baby Jesus, Herod of Rome tried to kill him. The magi disobeyed Herod and returned home “by another route.” When he learned that the magi had tricked him, Herod erupted in a furious rage and murdered all the male children two years old and younger who lived in Bethlehem and its vicinity.

|

|

Joseph and Mary.

|

And so, on December 28, our church liturgy will pivot sharply to a most counterintuitive feast day — "the slaughter of the innocents." The church honors the children of Bethlehem as the first martyrs of the gospel. By the late fifth century the "slaughter of the innocents" was the subject of church liturgy, art, and literature. It's a fitting sacred memory for our violent contemporary world with its child poverty, gun violence, and war-time displacements — "Rachel weeping for her children."

The baby Jesus then vanished into totally obscurity for thirty years, then emerged as a wandering trouble maker "with no place to lay his head." Rejected by his own family as insane, ostracized by the religious establishment as a boundary breaker, abandoned by his closest followers, he was executed as a criminal by Rome on charges that he "subverted our nation."

I'm not on Twitter or Facebook, but after endless terrorist attacks around the world — Nigeria, Sharm el-Sheikh, Beirut, Mogadishu, Ankara, London, Peshawar, Kabul, and Bamako, somewhere I saw the perfect sardonic post: "it's too bad that we don't have a narrative about Middle Eastern refugees spurned by society to help us think about these tragedies."

Christmas deconstructs all forms of Hallmark happy talk. It connects in a visceral way with our own world in which 60 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes. In which Syria bombs its own hospitals. Where Putin weaponizes winter to freeze the elderly to death. Where the lifeless bodies of little children wash ashore in Italy, Libya and Greece.

Paul calls Jesus "the good news of God" in the epistle for this week. Whereas the very first sentence of Matthew calls Jesus "the son of David, son of Abraham," Luke describes him as "the son of Adam" — that is, Jesus is not just the king of the Jews, he's the son of all humanity.

His story is for everyone. It originated with our Jewish forebears. It included Persian astrologers and enemy Egypt. It's for those in a lunatic asylum in the Mexican desert. For the children of Syria, and the refugees of Ukraine. And most certainly for our own broken hearts and homes.

And so we cry: "Lord, we bring our case before you, before you alone, for humanity has failed us."

And God responds: "The Lord himself will give you a sign. His name is Immanuel. God with us. He will save his people."

Weekly Prayer

Sr. M. Chrysostom, O.S.B.

The winds were scornful,

Passing by;

And gathering Angels

Wondered whyA burdened Mother

Did not mind

That only animals

Were kind.For who in all the world

Could guess

That God would search out

Loneliness.From Cyril Robert, Mary Immaculate: God's Mother and Mine. New York: Marist Press, 1946.

DaDan Clendenin:dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1–3) Amos Ferguson.