From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, "A Foreigner's Praise" (2019); Dan Clendenin, "A Theology of Geography" (2016) and "A Crisis is a Terrible Thing to Waste" (2013).

For Sunday October 9, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 29:1, 4-7 or 2 Kings 5:1-3, 7-15c

Psalm 66:1-11 or Psalm 111

2 Timothy 2:8-15

Luke 17:11-19

This Week's Essay

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain's Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

For many of us, part of the Sunday liturgy involves a recitation of one of the Christian creeds. It might be the longer creed forged in the debates of Nicea and Constantinople, or it might be the shorter creed used for baptisms, typically called the “Apostle’s Creed.” Other parish communities may use a more recently written creed. But did you know that the New Testament itself contains creeds? They’re sprinkled all over and none are more than a few lines. They capture what are probably the first liturgical materials developed by the early churches to practice their faith.

I wish we would use some of the biblical creeds more often in our contemporary worship services. The pastoral epistles to Timothy are chock full of them, and in our epistolary reading for today we get two: “Jesus Christ, raised from the dead, a descendant of David,” and then a subsequent text, marked off as a “sure saying.” Let’s explore this sure saying.

1. If we have died with him, we will also live with him.

In 1969, Donald Crowhurst mistakenly entered a contest to sail around the world, taking out heavy financial loans that, if defaulted, would have sunk his family into poverty. Out at sea, he realized he had no hope of actually completing the journey, much less winning. So he decided to fake his sailing logs and pretend to have circumnavigated the earth, hoping for last place so no one would inspect his log books too closely. Unfortunately, the other racers dropped out of the race, leaving him as the de facto winner if he finished, and sure to be discovered as a fraud. Damned either way, Crowhurst drowned himself at sea. I suspect many of us can relate to his paralyzing dilemma. Like Crowhurst, we’ve said or done things we can’t take back, made choices with reverberating consequences.

|

|

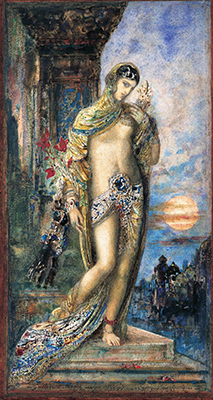

Song of Songs painting by Gustave Moreau, 1893.

|

Donald Crowhurst felt death was the only way out of his situation. He needed a complete do-over. The problem is, physical death is a one-way ticket. What we need is some way to die and live again without physically dying. This is what the early Christians realized. They saw their life with Jesus as sacramental, one of mystical union. They were in him and he was in them (John 17.21). Therefore, Jesus offering himself as a “ransom for many” meant that when he died on the Cross, they could die with him, and when the Father raised Jesus from the dead, they would rise from the dead with him. Jesus’ death and resurrection means new birth, new creation — starting over really is possible. By dying and rising with Jesus, we can be remade in the image of our Savior, free from our brokenness to face our responsibilities in this life with freedom rather than guilt.

2. If we endure, we will also reign with him.

Dying and rising with Christ does not mean life becomes easy. It means we are free to face our responsibilities purely out of love for our Savior, rather than according to the demands of a cruel world. There will often be suffering, especially because the grace of God offends the powers we’re subject to. Crowhurst’s despair was forced by a retributive financial system and unforgiving celebrity culture that would have certainly destroyed his family if he had returned home alive. Christian faith does not immediately end these realities, but it does point us to another dimension of being, one where our reward lies with Christ, not the expectations of our culture. Every person who chooses to endure brings us one step closer to the full in-breaking of the Kingdom of Heaven.

3. If we deny him, he will also deny us.

No one likes this part of the creed; it feels cold and harsh, out of step with the hopefulness of the previous two lines. Worse, it seems like a direct contradiction with the next line, that Christ is faithful even when we are faithless. What is going on here?

I suggest this line is much like Jesus’ parables about not being forgiven if we do not forgive. We cannot live our lives any old way knowing God will forgive us. To discourage this, the early churches first reminded themselves that we cannot expect the faithfulness of Christ if we will not ourselves be faithful. We have no rights here, no entitlement. It matters how we live; we are to “endure” in faithful living, not capitulate to the devil’s corruption. If we decide to deny the one who gave his life for us all, how can we expect anything except that he will deny us?

4. If we are faithless, he remains faithful — for he cannot deny himself.

And yet he cannot deny us, for he cannot deny himself. The very death and resurrection of Jesus testifies to the gracious God, the One who remains faithful even when we are faithless. The sternness of the third line that we not take our salvation casually is given balm by the fourth line’s assurance that our hope is not based on our own efforts, but on the unrelenting mercy of the Most High God. Even if we deserve denial because of our faithlessness, Christ remains faithful because that simply is his character, and he cannot deny himself.

|

|

Cymon and Iphigenia painting by Frederic Leighton, 1884.

|

With short, memorable sentences and a familiar cadence, creeds set before us the unequivocal heart of God in Christ. They paint pictures, in terse but pregnant words, of God’s love for us — not so that we can passively and mindlessly assent to them, but so that we can respond in kind to God’s love. In short, the work of the liturgy is to help people fall in love with what God has done for us in Jesus.

Wait, fall in love? What’s with all this mushy talk? Sometimes contemporary liturgy functions so much to make us feel better about ourselves that we forget the original purpose of worship and creed: to love God. Remember the greatest commandment, according to Jesus? “To love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength.” The purpose of each line in the 2 Timothy creed is to inspire awe and gratitude and desire in our hearts as we press deeper into Holy Love.

Love is about luxuriating in intimate connection. While certainly marriage centers around building up a family or crafting a home together or providing for the household, marital life is hard to sustain without space for the couple to just be in loving presence with each other. Philosopher Josef Pieper points out in his book Leisure that loving intimacy is defined in part by its lack of social practicality: “The lover, too, stands outside the tight chain of efficiency of this working world… .” There’s nothing practical about genuinely spending hours staring into each other’s eyes or going for walks in the countryside; lovers just enjoy each other’s company and cannot get enough of it. To be in loving intimacy is to just relish the goodness and joy of being together.

Isn’t that why we sing the Psalms? Re-read today’s hymns through the gaze of a lover. “I will give thanks to the Lord with my whole heart… Great are the deeds of the Lord… The Lord is gracious and full of compassion” (Psalm 111). “Bless our God, you peoples; make the voice of his praise to be heard; Who holds our souls in life, and will not allow our feet to slip” (Psalm 66). Like the creeds, we don’t say or sing these words because the Almighty needs our affirmations! No, we say them much like lovers repeat over and over the things that delight them in each other. “Be joyful in God!”

|

|

Song of Songs painting by Egon Tschirch, 1923.

|

Far from some new age approach to Christian faith, practicing our love for God as the love of lovers for each other is one of the oldest traditions in the Church. In times past, it was customary for preachers to have their culminating sermons come from Song of Songs, where the erotic love poetry of a Hebrew couple was taken as a magnificent image for Christ and the Church (already implied in Jesus’ own bridegroom and bride motifs). One reason why this might seem shocking to us today is because those of us who use lectionaries like the Revised Common Lectionary never really get to hear sermons on Song of Songs. Except for a few verses on a single Sunday in the three-year rotation, Song of Songs is entirely excluded from the RCL!

So I hope you’ll forgive me if I end on a text that is not in our assigned readings, simply because if I stick narrowly to them it will never come up. And perhaps those of us preaching should consider what texts are not getting heard on Sundays that we can work into our homilies. For the purpose of the liturgy and the creeds are to arouse our desire for the Lover of our souls. Love “burns like blazing fire, like a mighty flame,” and not even many waters can quench it (Song 8.6-7). May we let this creed in 2 Timothy set ablaze our hearts for the gracious tenderness of God, until we can say of Christ, “My beloved thrust his hand through the latch-opening and my heart began to pound for him” (5.4). I encourage you to read our Weekly Prayer below, taken from Song of Songs, and as you read, ask yourself, “What would it mean in my life for me to feel this kind of erotic desire for the Christ who remains faithful even when I am faithless?”

A Weekly Prayer

Song of Songs 4.1-7, 9-11

How beautiful you are, my darling!

Oh, how beautiful!

Your eyes behind your veil are doves.

Your hair is like a flock of goats

descending from the hills of Gilead.

Your teeth are like a flock of sheep just shorn,

coming up from the washing.

Each has its twin;

not one of them is alone.

Your lips are like a scarlet ribbon;

your mouth is lovely.

Your temples behind your veil

are like the halves of a pomegranate.

Your neck is like the tower of David,

built with courses of stone;

on it hang a thousand shields,

all of them shields of warriors.

Your breasts are like two fawns,

like twin fawns of a gazelle

that browse among the lilies.

Until the day breaks

and the shadows flee,

I will go to the mountain of myrrh

and to the hill of incense.

You are altogether beautiful, my darling;

there is no flaw in you.You have stolen my heart, my sister, my bride;

you have stolen my heart

with one glance of your eyes,

with one jewel of your necklace.

How delightful is your love, my sister, my bride!

How much more pleasing is your love than wine,

and the fragrance of your perfume

more than any spice!

Your lips drop sweetness as the honeycomb, my bride;

milk and honey are under your tongue.

The fragrance of your garments

is like the fragrance of Lebanon.

Early Christianity — at least those strands of it heavily influenced by forms of Platonism — was enormously drawn to Plato’s Symposium and its vision of ‘desire’; and from the second and third century onwards it began to discourse on this matter intensively. Although it could find little or nothing in Jesus’s teaching about eros as such, it did not read his views on love (agape) as in any way disjunctive from the Platonic tradition of eros. And what it did inherit from Jewish scripture, and then from the earliest rabbinic exegesis of scripture, was a fascination with the symbol of sexual union as a ‘type’ — indeed, in the Song of Songs the highest type — of God’s relation to Israel or Church.

— Adapted from Sarah Coakley’s God, Sexuality, and the Self, Cambridge University Press, p. 8

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via m.c.fitzpatrick@outlook.com

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.