For Sunday September 18, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 8:18–9:1

Psalm 79:1–9 or Amos 8:4–7

Psalm 113

1 Timothy 2:1–7

Luke 16:1–13

From Our Archives

Dan Clendenin, How Long, O Lord? (2007); Shared Civic Values (2016).

Debie Thomas, Notes to the Children of Light (2019).

This Week's Essay

In one of my favorite cartoons from the Chronicle of Philanthropy, a man who has died stands before the pearly gates. The celestial gatekeeper, bearing the obligatory wings and halo, looks down on the supplicant and advises him, "Charitable giving isn't the ultimate test of one's humanity, but it gives us some numbers to play with."

The parable of "the unjust steward" for this week occurs only in Luke 16. It's one of the craziest stories in the Bible, with one of the hardest-hitting punch lines in the gospels. Jesus says that how we relate to money is an important barometer of how we relate to God. He says that material wealth is one measure of our spiritual health. And like the cartoon, Jesus says that our choices in this life have consequences for the afterlife.

The parable begins with the words, "there was a rich man," and ends with a stark warning to people who "loved money." The next story that starts in Luke 16:19 begins with the identical words, "there was a rich man," although it considers wealth from the vantage point of the poor (Lazarus) rather than the rich. Similarly, the combined readings for this week consider money from the perspectives of both the rich and the poor.

Luke's parable has flummoxed readers because Jesus "commended the dishonest manager" (v. 8), even though his master fired him for poor performance and cheating. Knowing that he would be fired, the money manager cooked the books of his boss's clients so that they would owe him favors when he was unemployed. The commendation is directed not toward the manager's dishonesty per se, but "because he had acted shrewdly" (v. 8) regarding what he cared most about (money), and for averting a future catastrophe.

Jesus continues the story by drawing a parallel to the effect that if worldly people are so shrewd regarding something as insignificant as "worldly wealth" (note Jesus's irony), should not believers be even more shrewd about the "true riches" of the kingdom of God? Then, in a final twist, Jesus joins the two strands and concludes with a stark warning: "No servant can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and Money" (v. 13).

|

|

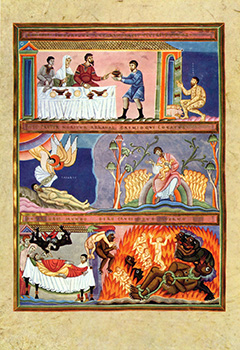

Hildegard of Bingen and the Unjust Steward; Codex Latinus 1942.

|

The gospel for this week ends there, but Luke continues by including the audience response. "The Pharisees, who loved money, heard all this and were sneering at Jesus." That Jesus characterizes the Pharisees as "lovers of money" is revealing, because by outward standards they were the most religiously scrupulous and zealous people of their day. They fasted, tithed, and observed the Sabbath with impeccable rigor. So, it's possible to be outwardly very religious and yet inwardly a "lover of money."

The Pharisees's deeper problem with money, said Jesus, revealed itself in a subtle but telling trait — self-justification: "You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of men, but God knows your hearts. What is highly valued among men is detestable in God's sight." So, we shouldn't let ourselves off the hook, give ourselves a free pass, or make self-justifying rationalizations about money.

However much the Pharisees related to money with an external religious righteousness, their self-justification indicated that something deeper, something more corrosive and pernicious, infected their hearts. They "highly valued" money; it was their "master" whom they loved and served, whereas in the upside down kingdom of God Jesus suggests that money is insignificant, and "highly detestable" (v. 15).

Two other readings this week connect wealth and discipleship, but this time from the perspective of the poor rather than the rich. Amos 8:4–7 and Psalm 113 both speak of the poor, the needy and the barren. How we treat money and how we treat the poor are two sides of the same coin. The psalmist describes the high and mighty God who "stoops down" from the heavens to tenderly care for the poor. He longs to "raise the poor from the dust, and lift the needy from the ash heap." He would reverse their fortunes, and "seat them with princes" (113:5–8).

People can be poor for many, complicated reasons — laziness, sickness, poor skills, bad choices, misfortune, mental illness, economic downturns, lack of educational opportunity, and so on. But Amos employs graphic language to describe people who are poor because rich people exploited them:

Hear this, you who trample the needy

and do away with the poor of the land,

Saying,

"When will the New Moon be over that we may sell grain,

and the Sabbath ended that we may market wheat?" —

skimping the measure, boosting the price, and cheating with dishonest scales,

buying the poor with silver and the needy for a pair of sandals,

selling even the sweepings with the wheat.

This text becomes all the more powerful when we remember how the rich often blame the poor for their poverty. They blame the victim. In fact, says Amos, it's the rich who "trample" and "crush" the needy. They "deny justice to the oppressed," and "deprive the poor of justice in the courts." Poverty has many causes, but sometimes there really is a powerful oppressor and a weak victim.

|

|

Lazarus and Dives, illuminated manuscript from the 11th century Codex Aureus of Echternach.

|

There are no easy answers to the hard sayings of Jesus. We shouldn't romanticize the poor or stigmatize the rich. That's a far too easy way out of a difficult passage about a complicated subject. The love of money doesn't depend on the size of your bank account. Broadly speaking, though, we can make two observations.

First, the historian Peter Brown has explored how Christians in the Roman Empire grappled with wealth. There's no unchanging or timeless "master narrative" here, says Brown, only changing views and shifting arguments from the ancient world of the third century to the early Middle Ages of the seventh century, on down to today.

Brown documents the various ways that the social imaginations of early believers grappled with wealth and salvation — from radical renunciation by the super rich like the desert mother Melania (one of the richest people in the empire), the "anti-wealth" of the ascetics, care of the poor, building hospitals, the generosity of ordinary believers, and, finally, the stewardship of massive wealth as God's providential gift.

Brown is especially interested in the consequences of the conversion of Constantine. He rejects "the great myth of the primal poverty of the early Christians." It's true that the church gained new privileges under Constantine, like tax exemptions, but other groups enjoyed similar and even better privileges. Nor did Constantine usher in a time of new wealth for the church. That did not happen for another generation, until the year 370 or so.

Until then, Brown credits the down-market "mediocres" or "in-betweeners" with being the church's biggest financial supporters — the "middling people" between the super rich and the oppressed poor, artisans, small farmers, small town clerics, tradesmen, and minor officials. These people who "knew their place" were "the solid keel of the Christian congregations through the fifth century."

This brings us to the second point. The sacrificial gifts of these ordinary believers were not just an expression of compassion for the poor. Social solidarity, compassion, and charity are all obvious reasons to help the poor, but Brown is especially interested in how alms giving also became a "purely expiatory action" for the atonement of sin, "to heal and protect one's soul."

In this view, giving alms were transactions calculated to transfer material wealth on earth to spiritual treasure in heaven. So, we're back to the use of wealth in this life as having consequences for the soul in the afterlife. Jesus seems to say that there's a "transfer" of earthly treasure to heaven through alms giving, and a spiritual reward for financial generosity.

|

|

The Rich Man and Lazarus, illuminated Psalter, England, c. 1160.

|

Gary A. Anderson makes this exact point. He argues that almsgiving is not just a utilitarian act of social justice to help the poor (Bill Gates does that), not only an ethical act done purely out of principle and altruism with no element of self-interest or expectation of reward (per Kant), and not merely a sign of a believer's personal faith (per the Protestant Reformers). Rather, for Anderson, a Catholic professor of Old Testament at Notre Dame, almsgiving is a "merit-worthy" deed that enjoys pride of place as "the privileged way to serve God."

Anderson focuses on two texts — Matthew 6:19–21 about treasure on earth or in heaven, and the Rich Young Ruler in Mark 10. Texts like these and others like Matthew 25 and Proverbs 19:17 ("Whoever is generous to the poor lends to the Lord") are to be understood literally and not metaphorically, says Anderson. There is a spiritual reward for financial generosity. God will repay the loans we have made to him.

Brown admits that such ideas are an "acute embarrassment" to unbelievers in general, and downright "abhorrent" to Protestants in particular. But one thing's for sure: we will all experience our own epiphany at death. We will learn how heaven and earth, material and spiritual wealth, are "joined by human agency." Our choices have eternal consequences. Only in heaven, said Mother Teresa, will we learn how much we owe the poor for helping us to love God.

NOTES:

Peter Brown,Through the Eye of a Needle; Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (Princeton, 2012); The Ransom of the Soul; Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western Christianity (Harvard, 2015); and Gary Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition (Yale, 2013).

Weekly Prayer

William Boyd Carpenter (1841–1918)

Before Thy Throne, O God, We Kneel

Before thy throne, O God, we kneel:

give us a conscience quick to feel,

a ready mind to understand

the meaning of thy chastening hand;

whate'er the pain and shame may be,

bring us, O Father, nearer thee.Search out our hearts and make us true;

help us to give to all their due.

From love of pleasure, lust of gold,

from sins which make the heart grow cold,

wean us and train us with thy rod;

teach us to know our faults, O God.For sins of heedless word and deed,

for pride ambitions to succeed,

for crafty trade and subtle snare

to catch the simple unaware,

for lives bereft of purpose high,

forgive, forgive, O Lord, we cry.Let the fierce fires which burn and try,

our inmost spirits purify:

consume the ill; purge out the shame;

O God, be with us in the flame;

a newborn people may we rise,

more pure, more true, more nobly wise.William Boyd Carpenter was a Bishop in the Anglican church, most notably in Ripon, England, where he served for twenty-five years.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) ParablesReception.blogspot.com; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.