For Sunday May 8, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 9:36-43

Psalm 23

Revelation 7:9-17

John 10:22-30

From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see the two essays by Debie Thomas, Tell Us Plainly; and Belonging; and then the two essays by Dan Clendenin: From The Old Eden to the New Jerusalem; and Peter the Apostle Meets Simon the Tanner.

Dan Clendenin founded JWJ in 2004.

Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine, I’ve struggled for some sort of Christian perspective on the barbaric war there that has killed thousands and displaced millions of ordinary citizens. The reading from Revelation this week helped me in many ways, albeit with one important qualification.

No book in the Bible has provoked more controversy, esoteric speculation, or sheer stupidity than Revelation. As late as the fourth century, Chrysostom and Eusebius hesitated to include Revelation in the canon. Martin Luther described it as "neither apostolic nor prophetic. My spirit cannot accommodate itself to this book." John Calvin wrote commentaries on every book in the New Testament except Revelation. In Eastern Orthodox churches today, Revelation is the only book that isn't read in their public liturgy.

|

|

The multitude in heaven.

|

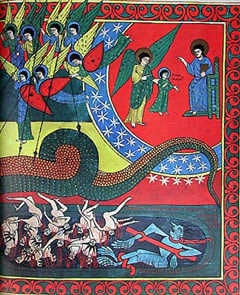

Part of the challenge is that Revelation is an example of “apocalyptic” literature that’s inherently difficult to interpret. As a genre that flourished from about 200 BC to 200 AD among both Jews (cf. Daniel 7–12) and Christians (cf. Mark 13), apocalyptic literature is characterized by visions, symbols, numerology, surreal beasts, and sea monsters, like a gigantic red dragon with seven heads, ten horns, and seven crowns.

The author identifies himself as John, but it's not clear whether he's the apostle John. He calls himself a “companion” of those who have “suffered for Jesus.” One thing is clear. The Roman government banished John 800 miles away to the tiny volcanic island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea. What did John say or do to provoke such wrath from the mighty empire? Why was he such a threat? Whatever the reasons, he didn't wallow in self pity, for it was on Patmos that he received and recorded his divine visions.

Silencing your critics has always been a reliable political tactic. Many governments exile or even murder their dissidents. Think of Thomas More in England, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, Óscar Romero in El Salvador, Bonhoffer in Germany, the Berrigan brothers in America, Jamal Khashoggi in Saudi Arabia, Alexei Navalny in Russia, and many other brave voices. Those who speak truth to power often pay a terrible price.

At one level you can read Revelation as a bitter critique of the Roman state. In her book Revelations; Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation (2012), Elaine Pagels calls Revelation a piece of "anti-Roman propaganda." She describes John of Patmos as a Jewish prophet in the tradition of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, all of whom wrote "war time literature," writing as he did soon after the persecutions under Nero in 64 AD, and after Rome ransacked Jerusalem in 70 AD.

|

|

Celestial creatures worship God.

|

Consider two grotesque images that John uses to describe Rome. It was a ferocious dragon that stood in front of a woman giving birth in order to "devour" the newborn son who would rule all the nations. Rome was also a prostitute "drunk with the blood of the saints." There are many persecuted minorities today for whom the state is what Nietzsche called the coldest of all cold monsters.

In Revelation, the Roman empire embodies and epitomizes all the forces of social violence, political oppression, religious persecution, economic exploitation, and cultural hubris that wreak so much devastation in history. John excoriates Rome as "Babylon the Great and the mother of prostitutes." He calls Rome the "city of power," where the human drama unfolds among "the kings of the earth, the princes, the generals, the rich, the mighty, and every slave and every free man."

By extension and comparison, Rome also represents "all domination systems organized around power, wealth, seduction, intimidation, and violence. In whatever historical form it takes, empire is the opposite of the kingdom of God as disclosed in Jesus" (Borg). We should ask not only why ancient Rome incurred God's judgment, but also what places and powers today mimic Rome and face a similar fate.

Some people complain that Revelation is too negative about the present, earthly world, and too focused on escaping to a future, heavenly world. But you might think differently if Janjaweed militia (literally, "devils on horseback") in Darfur had raped your women, if the Chinese government had subjected your Uyghur family to forced labor and sterilization, or if Russian jets had bombed your elementary schools and maternity hospitals. Herein, I think, lies one key to making sense of Revelation.

|

|

Seven angels with seven plagues.

|

In contrast to wealthy countries in the west, where citizens enjoy stable governments, poor people in much of the world suffer from corrupt dictators, mass displacements, starvation from forced famines, ethnic wars, environmental degradation, political repression, crushing debt, and grinding poverty. For them the apocalyptic themes of Revelation are not esoteric and irrelevant, but deeply relevant to their daily lives.

Divine intervention, healing, liberation, dreams, visions, miracles, and prophecies are lived realities rather than deconstructed myths for such Christians. Whether in ancient Rome or modern Zimbabwe, Revelation articulates our longing for God to intervene in human history and to make right all the wrongs: "How long, O Lord, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?"

Because of her crimes against humanity, Revelation predicts divine judgment for Rome:

Woe! Woe, O great city,

dressed in fine linen, purple, and scarlet,

and glittering with gold, precious stones and pearls!

In one hour such great wealth has been brought to ruin!

Woe! Woe, O great city,

where all who had ships on the sea

became rich through her wealth!

In one hour she has been brought to ruin!

Rejoice over her, O heaven!

Rejoice, saints and apostles and prophets!

God has judged her for the way she treated you.

This divine justice will bring about a dramatic reversal in human history. In a Biblical version of you reap what you sow, God will treat Rome as she has treated others. He will "pay her back double for what she has done, and mix her a double portion from her own cup."

This dramatic reversal includes a comprehensive restoration rooted in divine mercy. Revelation echoes Paul's vision of the redemption of the entire cosmos by a God who is the "Father of every family, in heaven and on earth." The Biblical story that began in Genesis with a fall in a garden ends in Revelation with a restoration in a city. The narrative progresses from Ancient Eden to the New Jerusalem.

On the very last page of the Bible, Revelation describes this plot fulfillment as "the healing of the nations." John envisions nations from around the world streaming to the holy city. In this week's text we read how divine mercy in the new Jerusalem heals all the human degradations of old Rome.

Never again will they hunger;

never again will they thirst.

The sun will not beat upon them,

nor any scorching heat.

And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.

In the New Jerusalem where all the nations of the earth gather, there will be no death, no mourning, no crying, or any pain. John expands the scale and scope of the cosmic consummation to include "a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language." This notion of a limitless ethno-linguistic inclusion is repeated several times (5:9, 11:9, 13:7, and 14:6).

|

|

Great red dragon with seven heads and ten horns.

|

I conclude with my one qualification.

After the emperor Constantine converted to Christianity on his deathbed in the year 337, Christians stopped criticizing Rome as a monster persecutor, and started embracing it as a benevolent protector. There eventually emerged a remarkable paradox: the greatest persecutor of the church (Rome) became its biggest supporter (Constantine) and the center of its ecclesiastical power (the Roman papacy).

This subsequent marriage of the church and state has caused a different set of problems. In Russia right now, Patriarch Kirill called Putin’s rule a “miracle from God,” and justified the slaughter in Ukraine as an apocalyptic war against western immorality. That's why we need the book of Revelation more than ever.

A Weekly Prayer

Walter Brueggemann (b. 1933)

Dreams and Nightmares

On reading 1 Kings 3:5-9; 9:2-9

Last night as I lay sleeping,

I had a dream so fair . . .

I dreamed of the Holy City, well ordered and just.

I dreamed of a garden of paradise,

well-being all around and a good water supply.

I dreamed of disarmament and forgiveness,

and caring embrace for all those in need.

I dreamed of a coming time when death is no more.

Last night as I lay sleeping . . .

I had a nightmare of sins unforgiven.

I had a nightmare of land mines still exploding

and maimed children.

I had a nightmare of the poor left unloved,

of the homeless left unnoticed,

of the dead left ungrieved.

I had a nightmare of quarrels and rages

and wars great and small.

When I awoke, I found you still to be God,

presiding over the day and night

with serene sovereignty,

for dark and light are both alike to you.

At the break of day we submit to you

our best dreams

and our worst nightmares,

asking that your healing mercy should override threats,

that your goodness will make our

nightmares less toxic

and our dreams more real.

Thank you for visiting us with newness

that overrides what is old and deathly among us.

Come among us this day; dream us toward

health and peace,

we pray in the real name of Jesus

who exposes our fantasies.

Walter Brueggemann (b. 1933) has combined the best of critical scholarship with love for the local church. Now a professor emeritus of Old Testament studies at Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia, Brueggemann has authored over seventy books. This prayer is taken from his book Prayers for a Privileged People (2008).

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1–4) www.Biblical-Art.com. All the images this week are from the 11th-century illuminated manuscripts of the book of Revelation by Stephanus Garsia Placidus, from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.