For Sunday January 23, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Nehemiah 8:103, 5-6, 8-10

Psalm 119

1 Corinthians 12:12-31a

Luke 4:14-21

If your pastor told you to feast, celebrate, and rejoice right now, because today is a day “holy to the Lord,” how would you respond? If one of your spiritual mentors insisted that this year — 2022 — is “the year of the Lord’s favor,” what would you say?

I’ll be honest; I would say, “You’ve got to be kidding me. This year? This one? Today? Right now? How can that possibly be?”

I don’t think I’d be alone in my skepticism. As I type these words, Omicron is overwhelming the planet. Hospitals are reaching capacity, physicians and nurses are exhausted, national and local economies are flailing, and Covid’s death toll continues to rise. And this is before we mention any of the other challenges facing us. Wars and threats of wars. Violence of all stripes. The catastrophic effects of climate change. The long shadow of racial injustice. Alarming breakdowns in civility and basic kindness. Rising epidemics of anxiety, depression, addiction, and despair.

Who on earth would reasonably call our current moment holy, or favored of God?

I ask, because our lectionary this week does exactly this. In two distinct stories of worship, two stories about people gathering to read, hear, and inwardly digest the word of God, we hear a call to attend to now. Both stories end with an invitation to recognize the sacredness of the present moment. Both stories insist that when we seek the divine — in worship, in the reading of scripture, in the intentional gathering of the beloved community — today shimmers with the presence, the blessing, and the favor of God.

This is true regardless of circumstances. Regardless of the trials we face, the sorrows we carry, and the pain we bear. Not because God’s exultant “today” is dismissive of our hardships, but because God’s presence infuses all things. God’s joy — the joy which is our strength — has within it the capacity to hold and honor our tears.

|

The first story this week is from the book of Nehemiah, and it describes a tender and hard won moment in Israel’s history. If you need some context: Nehemiah is a minor figure in the court of Artaxerxes, the king of Persia. When Nehemiah hears that Jerusalem is a broken, fire-razed wreck, he begs the king to let him return to his homeland and rebuild the city of his ancestors. The obstacles to the rebuilding are fierce and numerous, but Nehemiah persists, and finally succeeds in restoring Jerusalem’s wall and gates. He then invites his people back from exile, and asks them to gather in the square before the Water Gate for an assembly.

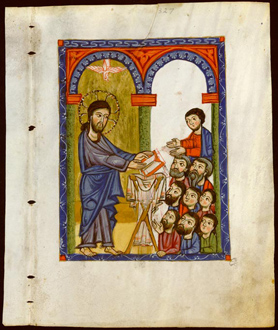

Our lectionary picks up there, at the moment when the prophet Ezra “opens the book in the sight of all people,” and reads from the law of Moses. He reads until the assembly of men, women, and children gathered in the square open their ears, stand up, raise their hands, worship “with their faces to the ground,” say, “Amen, Amen,” and weep. The story ends with Nehemiah and Ezra telling the people to dry their tears, return to their homes to “eat the fat and drink sweet wine,” and share the feast with those who are poor. Following an intense divine encounter, the people embrace the day and time they live in as “holy to the Lord.”

I love this story because it offers us a beautiful and multifaceted picture of what can happen when we seek the presence of God together, and allow that presence to infuse every part of our lives. Remember, the Israelites who gather at the Water Gate to hear the reading of the Torah are not people living in a “happily ever after,” all their trials and travails behind them. They are people newly returned from exile to a homeland that’s still in ruins. Their traumas are fresh and their future is unclear. Their most recent memories are memories of loss, dislocation, oppression, and chaos.

And yet, something powerful happens among them when Ezra opens the book and reminds them of who they are in the long arc of God’s story. What happens is not magic. Neither is it manipulation. What happens is transformation. As the people consent to listen to God’s word with their whole hearts, to receive what’s read in a spirit of openness and vulnerability, and to express their comprehension as honestly as they can, everything changes.

To be clear, the honesty they express includes sorrow, lament, and repentance. Ezra reads for hours — from early morning until midday — and in that time, the people enter into a period of deep reflection and remembrance. I imagine that when the Israelites hear the sacred stories of their tradition — the stories of the Exodus, the stories of God’s provision in the desert, the stories of their ancestors’ failures and rebellions — they feel everything from nostalgia to elation to horror to happiness. They weep in gratitude over God’s goodness. They weep in bewilderment over God’s silence. They weep in regret over their own sins. They weep in mourning for all they’ve surrendered or lost. And they weep in relief that the exile is over, and Jerusalem — razed though it is — is once again their home.

God’s word — living and active among them — holds all of this. It allows all of this, and blesses all of this. When the time is right, God transforms the entire encounter into an experience of joy.

|

The second story takes place centuries later, in the backwater town of Nazareth. It’s a Sabbath day soon after Jesus’s baptism and temptation in the wilderness. “Filled with the power of the Spirit,” Jesus returns to his hometown, enters the synagogue he has likely attended since boyhood, and stands up (as is the custom) to read from the Prophets. He asks for the scroll of the prophet Isaiah, unrolls it, finds the passage he wants, and reads aloud. By the time he’s finished reading, every eye in the synagogue is fixed on him.

Luke offers us this reading scene as the inaugural act of Jesus’s ministry. An act in which Jesus proclaims his identity, his purpose, and his vocation. What I love about the scene is that Jesus chooses to reveal the meaning of his life and work through the beloved and well-worn words of Scripture. Words his audience has heard a thousand times. Words no doubt rich with communal memory and meaning, but also words in danger of losing their power through over-familiarity. It’s not as if the Son of God is incapable of penning a new and shiny mission statement; he is the Incarnate Word himself. But he doesn’t improvise; he opens the book and makes the old words of the tradition his own: “God has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” As if to say: the Word lives, here and now. Today. It is organic, it breathes, it moves in fresh and revolutionary ways. The Word of God is neither dull nor dead. It is alive.

Of course (as we will see in next week’s lectionary) the opening of the book doesn’t always go smoothly for those bold enough to attempt it. Unlike the assembly that receives Ezra’s reading with open hearts, Jesus’s audience recoils in shock and outrage when he dares to suggest that the divine word is a word for their contemporary moment. They take offense at the fact that God’s “today” is not a day to postpone and defer. Not a cosmic fairytale ending to expect in some fuzzy, indistinct future.

Of course, what's surprising about this story is that the very people who need the freedom Jesus offers, find his invitation of freedom intolerable. What offends them is not the ancient prophecy of their beloved ancestor. After all, Isaiah’s words offer nothing but good news. No, what offends them is the suggestion that the good news is available right now. That the time for transformation, renewal, and metanoia is at hand. That they must change today. Lean into liberation today. Accept the joy of the Lord today. The time of the Lord’s favor — luminous and rich — stands in front of them, embodied before their very eyes, if only they will dare to see it. “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

|

As I contemplate these two stories, I realize how reluctant I am at times to embrace the holiness of “today.” Perhaps like some of you, I have spent the past two years living “on hold.” Deferring and deflecting, as if the days we live in right now don’t count as “real life.” “Real life will resume after the pandemic,” I tell myself. Real life will resume when church services go back to being in-person. When we can celebrate the Eucharist with bread and wine. When we put away our masks for good. When we get some sort of handle on climate change, police brutality, teen depression, and sectarian violence.

I wonder if I do this because I am like Ezra’s listeners, full of pent-up grief, longing, regret, and lament that have nowhere to go. Maybe I assume that I can’t lean into God’s joy until all my sorrows are spent. Or that worship can only be an articulation of happiness — not grief or anger or confusion or doubt. If so, can I remind myself that God’s embrace is wide enough to hold all of human experience? Can I trust that divine abundance is possible now, even in the midst of uncertainty and pain? Can I say “Amen” to God’s word in the complicated circumstances I live in right now? Today?

Or perhaps our ambivalence around “today” has more to do with a deep-seated fear of change. Like Jesus’s listeners, we long for liberation — but we want to control what that liberation looks like. We don’t want to face someone who looks and sounds and loves and probes like Jesus. How dare he mess with our traditions, our boundaries, our well-established norms around how God works in the world? We’d rather put salvation off than confront its alarming presence in our lives right now.

Perhaps we need to accept the possibility of holy discomfort. Perhaps the “now” of God means we have to stand up, shake the dust off, and move. What if the release of the captives and the healing of the blind require that we step out of our prison cells and open our eyes? It’s one thing to scan the horizon of someday for the “year of the Lord’s favor.” It’s quite another to live boldly into that favor now.

During this season of Epiphany, we are invited again and again to look for signs and glimpses of revelation. Of light. Of God's transformative presence. We are asked to hold in tension chronos time and kairos time — the linear, "ordinary" time we experience as human beings, and the sacred time of God's perpetual inbreaking. We are called to trust that even in the mundane day-to-day of life on earth, God's "now" brims with the possibility of joy and feasting.

“This day is holy to the Lord.” “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” May it be so.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Bible History Online; (2) Seattle Pacific University; and (3) Bible HIstory Online.