For Sunday March 21, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Jeremiah 31:31-34

Psalm 51:1-12 or Psalm 119:9-16

Hebrews 5:5-10

John 12:20-33

Our Gospel reading this week begins with desire: “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” The setting is Jerusalem, the occasion is Passover, and the people expressing the desire are Gentiles, visiting the city for its traditional religious festivities. The Gospel doesn’t tell us how many Gentiles come seeking Jesus, or why they’re interested in him. Are they curious about his message and his parables? Are they chasing spectacle — hoping to see a rumored miracle-worker walk on water or heal a blind man? Maybe they’re skeptics or troublemakers, looking to pick a fight with the controversial Messiah. Or maybe they’re just bored and seeking a distraction. We don't know.

But I’m grateful that the text leaves their motivations a mystery, because when I look at my own life, I recognize the Gentiles’ request in all of these guises. I know what it’s like to want Jesus in earnest — to want his presence, his guidance, his example, and his companionship. I know what it’s like to want — not him, but things from him: safety, health, immunity, ease. I know what it’s like to want a confrontation — a no-holds-barred opportunity to express my disappointment, my sorrow, my anger, and my bewilderment at who Jesus is compared to who I want him to be. And finally, I know what it’s like not to want him at all — what it feels like to shelve all spiritual desire, and allow my faith to fade into the background of my life and consciousness. I cycle between these wants. My heart for Jesus expands and constricts; my desire to see him waxes and wanes, and my motives for seeking him grow clearer and murkier by turns.

“Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” On its face, it’s such a simple request, but it cuts to the heart of spiritual growth, stagnation, and defeat. Do we want to see Jesus? Where does desire register in our spiritual lives right now? During this season of Lent, are we asking to see the Jesus we’ve heard so much about? If yes, which Jesus do we wish to see? The teacher? The healer? The peacemaker? The troublemaker? Why are we interested?

|

Or, if we’re not asking and seeking, then the question shifts, and we have to ask it differently: why is Jesus not on our radars? Does “seeing” him feel impossible right now? Uninteresting? Irrelevant? Has he become so familiar to us that he’s faded away entirely?

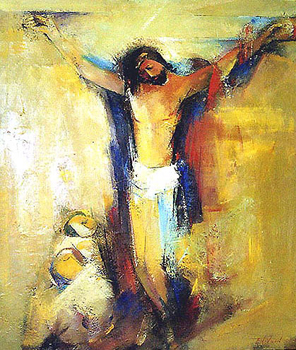

Immediately following the Gentiles’ request, Jesus launches into a meditation on his death. He says his hour has come. He describes himself as a grain of wheat falling into the ground and dying in order to bear much fruit. He invites his followers to “hate” their lives in this world and keep them instead for eternal life. He admits that he’s afraid: “Now my soul is troubled.” And finally, he describes the cross as a gathering place of agony, glory, unity, and communion: “When I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself.”

In a few weeks, many of us will gather online or in person to remember Jesus’s death, and keep vigil at the cross. As Covid restrictions allow, we’ll meditate, pray, sing, and weep. Alone or with others, we’ll kneel, or sing, or chant, or fast — all in the hopes of entering into the deep mystery of the crucifixion. All in the hopes of honoring what Jesus made possible when he was lifted up from the earth.

|

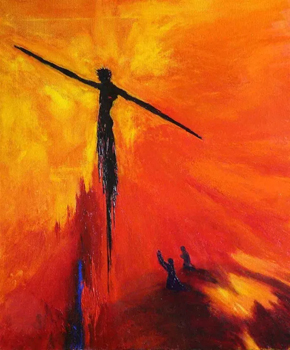

But for those of us who've grown up in the faith, I fear that the actual scandal and strangeness of Jesus’s death has perhaps long faded away. Do we know anymore which Jesus we wish to see? We’re used to worshipping in front of a crucifix; we cross ourselves without thinking, or wear tiny replicas of the cross around our necks. But what would happen, I wonder, if we could shake ourselves out of our familiarity for a few minutes, and see with new eyes what happened on Good Friday? God died. Jesus willingly took the violence, the contempt, and the hatred of this world and absorbed them all into his own body. He chose to be the victim, the scapegoat, the sacrifice. He refused to waver in his message of universal love, grace, and liberation, knowing full well that the message would cost him his life. He declared solidarity for all time with those who are abandoned, colonized, oppressed, accused, imprisoned, beaten, mocked, and murdered. He burst open like a seed so that new life would grow and replenish the earth. He took an instrument of torture and turned it into a vehicle of hospitality and communion for all people, everywhere. He loved and he loved and he loved, all the way to the end. “When I am lifted up, I will draw all people to myself.”

If we, like the Gentiles, want to see Jesus, we have to be willing to look at the cross. Yes, Jesus was and is many things: teacher, healer, companion, and Lord, and it is important that we experience him in all of these ways. But the center, the heart of who he is, is revealed at the cross. The cross makes true sight possible.

In my own life, I often flinch away from the Jesus of the Passion — the vulnerable, broken Jesus — because I want a muscular, superhero Jesus instead. I want the dramatic rescue, the quick save. I don’t want to learn the discipline of waiting at the tomb, in the shadowed place, in the realm where my questions far outnumber the answers. I am impatient for resurrection, and scorn everything that comes before it. I don’t think I’m alone in this struggle; many of us wrestle with the Jesus of Holy Week, because he looks so different from what we expect in a Savior. Often, we’re not entirely sure who we’re looking for.

In the end, what this week’s Gospel reading teaches me is that I don’t have to strive and strain to see Jesus. As he told those Gentile seekers two thousand years ago, he is the one who draws and gathers all people to himself. He is the one who allows himself to be lifted up, so that what is murky or overwhelming or frightening — God in his indecipherable Otherness — comes close and becomes visible.

|

In other words, Jesus desires steadily when I desire unsteadily. He loves whether I love or not. It has taken me a long time to lean into this possibility, and it still eludes me sometimes, but I choose to trust this, as best I can: Jesus’s longing for me is the ground upon which all of my desire — however abundant or stingy — rests. He wishes to see me — to see all of us — far more urgently than we’ll ever wish to see him. This isn’t a rebuke. It isn’t an invitation to self-loathing or shame. Rather, it is a promise and a refuge. We love because he loves first. We love because the cross draws us towards love — its power is as compelling as it is mysterious. The cross pulls us towards God and towards each other, a vast and complicated gathering place. Whether or not I want to see Jesus, here he is, drawing me. This is the solid ground we stand on. Stark, holy, strange, and beautiful.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Kazuya Akimoto Art Museum; (2) DiscipleshipMatters.org; and (3) ArtLondon.com.