For Sunday January 24, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Jonah 3:1-5, 10

Psalm 62:5-12

1 Corinthians 7:29-31

Mark 1:14-20

Maybe, once upon a time, there was time. Time to dawdle. Time to procrastinate. Time to delay. Maybe, in that idyllic yesteryear, there was leisure to tell ourselves that we don’t need to hurry. That we can afford to hang back. That someone else will come along and fix this mess. Because we’ve got time.

If such a “once upon a time” ever existed — and honestly, I doubt it did — it doesn’t exist anymore. As our lectionary texts for this week make abundantly clear: “The time is fulfilled.” The time is now.

In our reading from the Hebrew Bible, Jonah shouts a terrifying countdown across the streets of Nineveh: “Forty days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” In his first epistle to the Corinthians, Paul tells his readers to make swift and serious lifestyle changes because “the appointed time has grown short,” and “the present form of this world is passing away.” In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus arrives in Galilee with an urgent, no-nonsense message: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near.”

Do we believe any of this? I mean, really, deep in our hearts, when push comes to shove, do we believe that our faith makes urgent, time-sensitive claims on us? Or are we offended at the thought that our spiritual casualness has real-world consequences?

Like many of you, I am still reeling from the January 6th attack on the U.S Capitol Building. Specifically, I am reeling from the version of Christianity I saw on display among the mobsters. A version that saw no contradiction between “Jesus Saves” slogans and lethally violent assaults against unarmed national leaders. As a progressive Christian who holds tolerance, open-mindedness, and religious diversity in high regard, I am having to take a hard step back. As in: the truth of the Gospel is not, finally, an interpretative free-for-all. There are limits to tolerance, and those limits sometimes involve life and death. Jesus never said, “Everything goes.” If the message, “Jesus Saves,” has been successfully co-opted to further nationalism, white supremacy, lawless violence, and hatred, then I must ask myself what my own spiritual dawdling has wrought. How have I failed to read the urgency of these times? When have I remained silent when I should have spoken? How have I allowed my commitment to open-mindedness to slide into complicity? Why have I minimized the uncomfortable truth that what we believe about God really, really matters?

These are painful questions, and I tremble at the thought of taking them on in a sustained way. But we cannot afford to shy away from them any longer. The time has come for an honest reckoning with the truth and scope of the Christian story in the public square. Do I cherish the Good News enough to share it? Or don’t I?

|

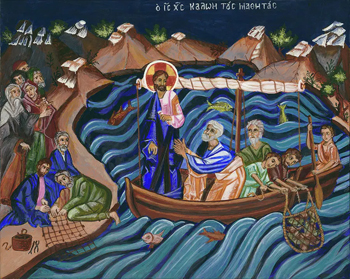

In our Gospel reading this week, Jesus invites four seasoned fishermen to leave their boats behind and follow him, so that he can make them “fish for people.” I’ll be honest: I’m not a big fan of Jesus’s fishing metaphor. When I was a little girl, my father would take me along on occasional fishing trips, and I would invariably ruin them with my squeamishness. I’d cry over the fate of the worms we used for bait. I’d wince at the hooks that ensnared our prey. I’d beg my dad to release every sleek and silvery fish he caught, because I couldn’t bear to see the poor things flopping in a bucket.

Hard as I tried to enjoy the sunlight on the water, the ocean breeze, the satisfaction of a good catch, I just couldn’t get over what I saw as the essential violence at the center of fishing: a living creature offered up as bait. Another living creature torn by a sharp hook, or hauled out of its native element by net, and left to die for lack of air. Eventually, my dad took the hint, and my brother — who enjoys fishing to this day — took over as his seafaring companion.

To be fair, my dislike for the metaphor isn’t merely literal. When I was growing up, “fishing” as an analogy for evangelism was framed in a very particular — and very arrogant — way. The "fish" were all the world’s non-evangelical souls, doomed to hellfire because they had no one to "catch" them. “Hooking” them for Jesus — getting them to church, to youth group, to the altar; leading them to say the sinner’s prayer and accept Jesus as their personal Savior; insisting that only our version of Christianity held the “Truth" which would save them from damnation — was the only hope these poor fish had. So. Was I ready to give up everything, leave all I know and love, and follow Jesus? Was I willing to fish for lost souls? Or would I cling to my worldly nets, ignore Jesus’s call, and let countless sinners burn in hell without any hope for salvation?

These days, I wonder if my reticence and non-urgency when it comes to evangelism is an understandable but unhealthy overreaction to the version of spiritual “fishing” I grew up with. I don’t believe I’m alone in this overreaction; many of us in progressive Christian circles are so afraid of coming across as zealous, arrogant, disrespectful, or coercive, that we avoid all public articulations of our faith.

What would it be like to find a more nuanced way forward? What would it look like to return to Jesus’s urgent invitation, and learn how to “fish for people” in ways that are hospitable, loving, generative, and nourishing? Can we learn to preach repentance in the way Jesus preached it — not as condemnation, not as cultural erasure, not as supersessionism — but as Good News?

Two insights about Jesus’s invitation might help us to address these questions. First, Jesus’s call in this fishing story is specific and particular, rooted in the language, culture, and vocation his hearers know best. What metaphor would make more sense to four fishermen than the metaphor of fishing for people? Simon and Andrew understand the nuances of that metaphor in ways I never will. James and John know from years of hard won experience what depths of patience, resilience, intuition, and artistry professional fishing require.

These men know the tools of the trade, the limitations of their bodies, and the life-and-death importance of timing, humility, attentiveness, and discretion. Most of all, they know the water. They know how to respect it, how to listen to it, and how to bring forth its best for the good of all. They understand and respect the reciprocity at the heart of their enterprise. They know not to take more than they need. They know to care for the life cycles of the fish. They know to pay attention to the health and sustainability of the marine environment that nourishes them and their families.

|

In other words, when Jesus calls these tried-and-true fishermen to follow him, they understand the call not as a directive to abandon their intelligence, intuition, and experience, but to bring the best of those gifts forward for the sake of a more beautiful and peaceable world — a world where all are nourished. The call is to become even more fully and freely themselves for the sake of God’s kingdom.

What can we learn from this? We can learn that we’re not called to evangelize in the abstract. We’re not invited to proclaim the good news “in general,” with no regard for how and where our words might land. We’re not invited to peddle cheap or careless language. We’re not commissioned to entrap or ensnare. Instead, we’re called to pay close and loving attention to the people around us. We’re called to “know the water.” We’re called to live, move, speak, and “fish” in ways that are reciprocal, respectful, and mutually life-giving.

In other words, if we’re going to follow Jesus at all, we have to do it in the highly specific particulars of the lives, communities, cultures, families, and vocations we find ourselves in. We have to trust that God prizes our intellects, our memories, our backgrounds, our educations, and our skills, and that God will multiply and bring to fruition everything we offer up in faith from the daily stuff of our lives.

Jesus says, “Follow me, and I will make you…” This is a promise to cultivate, not to sever. It's a promise rooted in gentleness and respect — not violence and coercion. It's a promise that when we dare to let go, the things we relinquish might be returned to us anew, enlivened in ways we couldn't have imagined on our own.

Most importantly, it is a promise from God to us — not from us to God. As Barbara Brown Taylor so aptly puts it, Mark 1:14–20 is a miracle story. Jesus calls, and the four fishermen “immediately” follow. No hesitation, no questions asked. Is this because they’re men of superhuman courage or prophetic foreknowledge? Of course not. These are the same guys who later in the Gospel doubt, deny, and abandon Jesus. They’re as fallible and as ordinary as the rest of us, and their own volition can’t get them very far. No, they immediately follow Jesus because Jesus makes it possible for them to do so. “This is not a story about us,” Taylor writes. “It is a story about God, and about God’s ability not only to call us but also to create us as people who are able to follow — able to follow because we cannot take our eyes off the one who calls us, because he interests us more than anything else in our lives, because he seems to know what we hunger for and because he seems to be food.”

What bothered me as a child — and bothers me still — about the fishing metaphor is that we so easily misinterpret it to mean that we have the power to “hook” or to “catch” others for God. We don’t. We are not called to cajole, manipulate, trap, bully, or even persuade others to “accept” Jesus, or join our religion. It is God alone who captures the imagination. God alone who makes the vision of the kingdom come alive in a human soul. What we must do is embody the vision in the particulars of our lives, reflecting into the water the profound beauty of who Christ is. The rest is up to God.

The second insight about Jesus’s fishing metaphor comes from the fascinating research of K.C. Hansen, who describes the socio-economic and political context of Jesus’s ministry in his article, “The Galilean Fishing Economy and the Jesus Tradition.” According to Hansen, the four fishermen in Mark’s story aren’t individual workers in a free enterprise system. By the time Jesus starts recruiting disciples, the fishing industry in Palestine is fully under the control of the Roman Empire. Caesar owns every body of water, and all fishing is state-regulated for the benefit of the urban elite. Fishermen can’t obtain licenses to fish without joining a syndicate, most of what they catch is exported — leaving local communities impoverished and hungry, deprived of the dietary staple they’ve depended on for centuries — and the Romans collect exorbitant taxes, levies, and tolls each time fish are sold. To catch even one fish outside of this exploitative system is illegal.

|

In this context, what is Jesus saying when he invites the four fishermen to leave their nets and “fish for people?” In his book, Binding the Strong Man, theologian and activist Ched Myers argues that we narrow and distort the radical nature of this text when we interpret it as an invitation to issue altar calls. Jesus isn’t talking about filling pews or baptismal fonts; he is hearkening back to the Hebrew scriptures, in which “the hooking of fish” is a euphemism for judgment upon the rich (Amos 4:2) and the powerful (Ezekiel 29:4). In other words, when Jesus asks Simon, Andrew, James, and John to “fish for people,” he is asking them to cast aside the existing social order of power, privilege, exploitation, and domination, and to help usher in God’s kingdom — a kingdom of justice for the poor, mercy for the oppressed, and abundance for all. He is, in Myers words, inviting commoners “to a fundamental reordering of socio-economic relationships.” To a new and God-honoring way of life that blesses all people.

In the end, Jesus’s proclamation is gospel, or “good news.” If it’s not good news, it’s not God. Evangelism becomes abusive when we individualize it for our own convenience, severing it from its broader social, economic, and cultural context. It becomes abusive when we forget respect and reciprocity, when we "fish" to boost our own egos in ways that are selfish and loveless. It becomes abusive when we focus on numbers, formulas, and institutions, forgetting that Jesus invites us to call people. People who are caught in the nets of exploitation, corruption, poverty, war, exile, homelessness, violence, disease, climate change, racism, and sexism. What might count as Good News for people ensnared by such brokenness and cruelty?

The four men “immediately” leave their nets to follow Jesus. Do we share their sense of urgency? Their sense that immediacy is required? In time, the disciples make the Gospel their own, sharing its radical power through the details of their own lives and stories. What is the Gospel according to you, here and now? What is your Good News, and how will you share it in the turbulent waters of your time and your place? “Follow me and I will make you….” This is a promise to lean into. Now.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Circle of Hope; (2) Ancient Faith Ministries; and (3) Wordpress.com.