For Sunday May 3, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 2:42-47

Psalm 23

1 Peter 2:19-25

John 10:1-10

For almost ten years now, a group of Christians have gathered on Sunday mornings at Friendship Park, a plaza along the U.S-Mexico border wall, to share worship and Communion. I read about the gatherings this week, in an article by Amy Frykholm, who visited the community last November. (“Worship Through A Wall.”) Apparently, this “border church” has survived every obstacle the U.S Border Patrol and shifting United States/Mexico relations have thrown at it.

If, for example, the border patrol won’t allow the two sides to stand close enough to hear each other’s words, they’ll stand fifty feet apart, and conduct worship over cell phones. If the participants are forbidden to pass food and drink through the fence, they’ll practice “sacramental solidarity,” and serve parallel Eucharists on each side of the border. Some years ago, when the chain-link border fence gave way to a steel barrier, worshipers continued to pass the peace across the border — pinky to pinky through tiny holes in the wall. Even these days, under Covid-19 lockdown, the church meets via Zoom and Facebook Live.

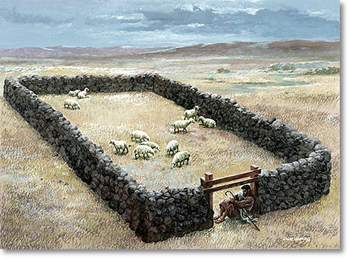

It was helpful for me to read Frykholm’s article as I prepared to write this essay. For the fourth Sunday of Easter (traditionally known as “Good Shepherd” Sunday), the lectionary offers us a Gospel passage so dense and layered, it’s easy to get lost and bogged down. In ten verses of packed metaphor, John gives us sheep, a sheepfold, a shepherd, a gate, a gatekeeper, a pasture, a sneaky band of thieves and bandits, and an even more sinister group of smooth-tongued “strangers.” At one point, the Gospel writer comes right out and says, “Jesus used this figure of speech with them, but they did not understand what he was saying.” No kidding!

It’s tempting to treat this section of Scripture as if it’s written in some obscure code. As if our job is to crack its many secrets. What exactly does the sheepfold represent? Heaven? The Church? Our hearts? Who are the thieves and bandits? Are they different from the “strangers” with the creepy voices? What about the gatekeeper? Is the gatekeeper God? The Holy Spirit? Jesus himself? No, wait, how can Jesus be the gatekeeper if he’s the gate? Doesn’t he say he’s the gate — twice? Actually, how can he be the gatekeeper or the gate, if he’s the shepherd?

|

It’s also tempting to read this passage from a place of complacency and privilege. To assume that we are automatically the “insiders,” snug inside the sheepfolds of our own merits. That we’re never the sheep who heed the stranger’s seductive voice. That we never resort to deceptive shortcuts instead of “entering through the gate.” That we never play the role of bandit or thief in other people’s lives. That we unerringly follow the lead of the shepherd when he ventures into new and risky terrain.

But I don’t think this passage of Scripture is meant to stump us or flatter us. I think it’s meant to reveal Jesus to us. Yes, Jesus the Good Shepherd, who offers us guidance, nurture, direction, and protection. But also more.

For me, a particular revelation of Jesus happened when I thought about the metaphors in this Gospel passage alongside Frykholm’s article about the tenacious little border church between the United States and Mexico. Suddenly, as I imagined eager, loving hands reaching through small gaps in a cold, steel barrier, as I pictured the insistent sharing of song, prayer, bread, and wine across a bleak, intractable border, the resonance of Jesus’s metaphor hit me full force. “I am the gate.” Not, “I am the wall, the barrier, the enclosure, the dividing line.” Not, “I am that which separates, isolates, segregates, and incarcerates.” I am the gate. The door. The opening. The passageway. The place where freedom begins.

Needless to say, most of us — left to ourselves — don’t associate “gates” with freedom. We think of bars and locks and alarms and enclosures. We imagine toddler gates, maybe, or puppy training gates. Prison gates and “gated communities.” But what if Jesus is a different kind of gate? A gate that opens out instead of closing in? Not the barrier itself, but the aperture in it? A place of release? Movement? Spaciousness? Liberty? “I am the gate. Whoever enters by me will be saved, and will come in and go out and find pasture.”

I know that this chapter of John’s Gospel has been interpreted in ways that harm people. I grew up hearing it as an exclusivist, supersessionist text, all about who is “in” and who is “out" when it comes to God and God's flock. For years, I read it as Biblical proof that Jesus won’t love or save people who don’t look, act, think, believe, pray, love, or worship in the same ways I do.

|

But in fact, this passage, at its heart, is not about scarcity at all. It’s not about the stinginess of God, and it’s not about the self-protective walls we like to build and hide behind. (Remember, Jesus is the gate. We’re not. Gate-keeping is not our job.) It’s about life. Life that pushes across formidable boundaries. Life that flourishes in precarious places. Life that never denies the real threat of thieves, bandits, and strangers — and yet holds out the possibility of pasture, nourishment, protection, and rest. Life that perseveres and maybe even thrives in the valley of the shadow of death.

Life that reaches through any opening it can find, however small, however fragile, however tenuous, and insists on generous self-giving: “This is my body, given for you. Take and eat.”

Some historians argue that shepherds in Jesus’s day often placed themselves across the openings of their sheepfolds during times of danger, literally offering up their bodies for their flocks. Jesus as shepherd. Jesus as gate. Jesus as sacrificial lamb, slain for us.

Maybe the questions we need to ask about this passage aren’t “code breaking” questions. Maybe they’re personal ones. What is it in me that resists the open gate? Where in my life am I walled off, closed to change, averse to movement, risk, freedom, joy? What flock do I belong to, and whose voice do I follow most readily? What calls to me, making seductive promises I shouldn't trust? Do I know the shepherd well enough to recognize his call? Am I willing to leave the fold in order to find pasture, or am I too complacent, scared, suspicious, and jaded to pursue abundant life?

|

In the coming weeks, many of us will face these questions in the very particular context of the coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath. The temptation to close our borders and lock our gates will be very, very strong. The fear of death will linger, and it might completely overwhelm us. A thousand seductive voices will speak into our ears, promising versions of security that have nothing to do with Jesus’s abundant life. Thieves will come to steal and kill and destroy, and so much — so much — will depend on what we believe about the nature and character of our sheepfold, our flock, our shepherd, our gate.

At the end of her article, Amy Frykholm quotes John Fanestil, one of the founding pastors of the church in Friendship Park. Fanestil says he shows up each Sunday to demonstrate the “true nature of the border.” Where others see a place of crime, fear, death, and hopelessness, Fanestil insists that those who gather for worship and Communion each week see “a place of encounter, exchange, friendship, and fellowship.” In other words, they make it their practice to see Jesus. Jesus, the gate. Unlocked. Wide open. Inviting. Free. May we have eyes to see him, too.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) The Preachers Word; (2) Fine Art America; and (3) Painting Star.