For Sunday [month] [day], 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29

Luke 19:28-40

Like many of you, I’ve celebrated Palm Sunday every year since I was a little kid. I know how to make clever crosses out of palm branches. I know all the verses of "All Glory, Laud, and Honor.” I know how to shout "Hosanna!” at the top of my lungs as Jesus makes his triumphant entry into Jerusalem. But what I didn’t know until this week is what the word “hosanna” actually means. All these years, I thought it meant some churchy version of “We adore you!” or “You rock!” or “Go, king!” It doesn’t. In Hebrew, it means something less adulatory and more desperate. Less generous and more demanding. It means, “Save now!”

Confession: this year, I come to Holy Week tired, scared, and hungry. Tired of God’s hiddenness or absence, and tired of my own lonely, unsteady heart. Scared of all the stones sealing all the graves I don’t believe a miracle will roll away. Hungry for a would-be gardener God to find me at the tomb and call my name. Hungry for a million small and large and ordinary and extraordinary resurrections. This is me, cloak and palm branches at the ready, waiting with a mile long list of expectations for a mighty king to come down the mountain and rock my world. This is the meaning of my hosanna. Save now. Not, “I love you." Not, "Your will be done." Not, "I praise you as you are, you gentle, vulnerable, weeping, suffering God.” Save now.

If the Palm Sunday story is about anything, it’s a story about disappointed expectations. A story of what happens when the God we want and think we know doesn’t show up, and another God — a less efficient, less aggressive, far less muscular God — shows up instead. When that happens, when our cries of “save us now” are met with heartbreaking silence, our hosannas go dark and our palm branches wither. We walk away, we close our hearts, and we deny and betray the image of God in ourselves and in each other. If push comes to shove, our hosannas give way to hatred, and we strike to kill.

|

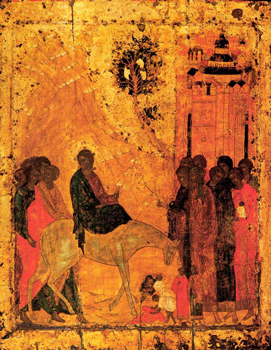

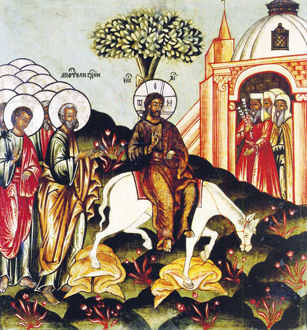

Historians tell us that Jesus knew exactly what he was doing when he asked his disciples to secure a donkey for his journey down the mountain into the holy city. In their compelling book, The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus' Last Days in Jerusalem, Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan argue that two processions entered Jerusalem on that first Palm Sunday two thousand years ago; Jesus's was not the only Triumphal Entry.

Every year during Passover — the Jewish festival that swelled Jerusalem's population from its usual 50,000 to at least 200,000 — the Roman governor of Judea would ride up to Jerusalem from his coastal residence in the west. He would come in all of his imperial majesty to remind the Jewish pilgrims that Rome demanded their complete loyalty, obedience, and submission. The Jewish people could commemorate their ancient victory against Egypt and slavery if they wanted to. But if they tried any real time resistance, they would be obliterated without a second thought.

As Pilate clanged and crashed his imperial way into Jerusalem from the west, Jesus approached from the east, looking (by contrast) ragtag and absurd. Unlike the Roman emperor and his legions, who ruled by force, coercion, and terror, Jesus came defenseless and weaponless into his kingship. Riding on a donkey, he all but cried aloud the bottom-line truth that his rule would have nothing to recommend it but love, humility, long-suffering, and sacrifice. So often, I think I know exactly what kind of savior I need. The savior of the swift repair, the majestic intervention, the tangible presence, the butter soft landing. But here’s the thing: that savior is not Jesus.

If there’s a single day on the liturgical calendar that illustrates the dissonance at the heart of our faith, it’s Palm Sunday. More than any other, this festive, ominous, and complicated day of palm fronds and hosanna banners warns us that paradoxes we might not like or want are woven right into the fabric of Christianity. God on a donkey. Dying to live. A suffering king. Good Friday.

|

These paradoxes are what give Jesus’s story its shape, weight, and texture, calling us at every moment to hold together truths that seem bizarre, counterintuitive, and irreconcilable. On good days, I understand that these paradoxes are precisely what afford my religion its credibility. If I live in a world that's full of pain, mystery, and contradiction, then I need a religion robust enough to bear the weight of that messy world. I need a religion that empowers me, in Richard's Rohr's beautiful words, "to live in exquisite, terrible humility before reality." But the question is: will I choose the humble and the real? Or will I insist on the delusions of empire? Will I accompany Jesus on his ridiculous donkey, honoring the precarious path he has chosen? Or will my impatient and broken hosanna undermine my journey?

In reference to Palm Sunday, Frederick Buechner writes this: “Despair and hope. They travel the road to Jerusalem together, as together they travel every road we take — despair at what in our madness we are bringing down on our own heads and hope in him who travels the road with us and for us and who is the only one of us all who is not mad.”

Buechner is right: we are mad with despair and hope, both, so much so that we don't know what to do with the story of a God who comes to die so that we can live. For those of us who struggle to reconcile the role of God's will in the death of Jesus, Palm Sunday offers us a terrible, beautiful, please-pay-attention clue: it was the will of God that Jesus declare the coming of God's kingdom. A kingdom of peace; a kingdom of slow, self-emptying love; a kingdom of radical embrace, radical patience, and radical risk that demands from us a degree of trust, vulnerability, and courage that empire can’t even imagine.

Jesus died, not because a furious Father in heaven needed to kill his precious son in order to love us, but because Jesus unflinchingly fulfilled the will of God. He died because he exposed the ungracious sham at the heart of all human kingdoms, holding up a mirror that shocks us at the deepest levels of our imaginations. Even when he knew that his vocation would cost him his life, he set his face "like flint" towards Jerusalem. Even when he knew who'd get the last laugh at Calvary, he mounted a donkey and took Rome for a ride.

What, I wonder, would Jesus-on-a-colt have to say about our obsession with ease and efficiency, prosperity and certainty, safety and immunity? Where and how would his parade-of-the-radically-vulnerable speak truth to today’s centers of power?

|

I don’t mean for a minute to write glibly, as if the Jesus to whom I daily cry, “Save now!” doesn’t break my heart. He does. Every single time I pray my yearning hosanna and Jesus doesn’t give me what I long for, my heart breaks again. The truth is, I want and I want and I want, so much more than I praise and I praise and I praise. I know that I’m supposed to love the God-on-a-colt who overturns all my expectations of what divinity should look like and act like. In theory, I do love him. But in practice, I daily pass him over, train my eyes on the horizon, and hold out hope for the emperor.

In the end, my solace is this: it’s not that I hold paradox, it's that paradox holds me. I am held and braced by a God who is too big for thin, one-dimensional truths — even my own, most cherished, one-dimensional truths. I am held by a God who sticks with me even when I won’t stick with him. A God who accepts my worship even when it is mingy, half-baked, and selfish. A God who knows all the reasons my heart cries, “Save now!” and carries those broken, strangled cries to the cross for me and with me.

Still. Still the truth is, I am afraid of what lies ahead. Who knows how many deaths lie waiting around the corner? How many sorrows, disappointments, farewells, and jagged endings I or you must face before resurrection comes home to stay? I can’t imagine most of it, and sometimes I can't bear any of it. But Jesus can. If anything in this Christian story is true, then this must be true as well: Jesus will not leave us alone. There is no death we will die, small or big, literal or figurative, that Jesus will not hold in his crucified arms.

Welcome to Holy Week. Here we are, and here is our God. Here are our hosannas, broken and unbroken, hopeful and hungry. Blessed is the One who comes to die so that we will live.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wordpress.com.