For Sunday March 31, 2019

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Joshua 5:9-12

Psalm 32

2 Corinthians 5:16-21

Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

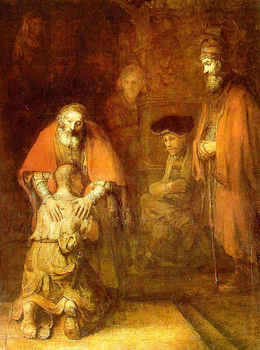

"There was a man who had two sons." So begins one of Jesus’s best-known stories about love and lostness, “The Parable of the Prodigal Son.” I was a little girl in Sunday School when I first learned about the boy who ran, the boy who stayed, and the dad who threw the big party. I liked the story very much — especially the details about the pigs and the party. (Charlotte’s Web was my favorite novel at the time, and what kid doesn’t love a big celebration?) But as the years went by, and I heard the parable over and over again, it began to lose its power. The younger son’s selfish greed, the older son’s arrogant fury, the patient father’s extravagant love… all the story’s meanings started to go in one ear and right out the other. As Barbara Brown Taylor puts it, the parable became limp from too much handling.

In many ways, I’m still struggling with this limpness. A few years ago, I tried to remedy it by writing imaginary letters to the two sons in the parable. My hope was to make the brothers real and relevant again, and to somehow find my own story mirrored in theirs. When I read over those letters this week, they still felt like the truest responses I can offer right now to Jesus’s famous parable. So here are the two letters I wrote about the shapes and forms of lostness. Here’s what I wish I could say to the boys whose father ached to bring them home.

To the Boy Who Ran:

I begin with you, because you're the strangest and least accessible to me. Impetuous. Careless. Demanding. So selfish, you take my breath away.

On the face of things, you and I have little in common. I've never run away, or squandered an inheritance, or given myself over to “dissolute living.” But neither have I felt the ardent, tear-soaked embrace of a lovesick father — human or divine — welcoming me home. Maybe this is why I dislike you. Am I envious because God is generous? Am I hurt because the father's love is a wild, unfettered thing, unpredictable and unfair? Yes, I am. YES. I AM.

|

Here’s what I’d like to know: was your penitence genuine? Did you mean that pious speech you composed in the pig sty, or were you just a clever talker, well-versed in your father's soft spots? Did you feel bad about your adventure, or just bad that it failed dramatically?

Here’s the other thing I’d like to know: did you get your act together, once the party was over and the fatted calf was eaten? Did you get up early the next morning and pull your weight in the fields? Did you apologize to your brother? Take care of your father? Make peace with the villagers you scandalized? Did you understand in your heart that really, there’s no such thing as going home? Not in any simple way? Did you get that everything — everything — would have to change?

Here's what I really need to know: what is this bitter root in me, that needs a guarantee? That wants to make sure you understood just how much fear, destruction, and sorrow you caused, before I let you off the hook? Why do I need to withhold the forgiveness that alone might restore you? What will I gain if you bleed repentance first?

I know this is a problem. My spite. My withholding. Everything in me accuses you of having no empathy — of not giving a damn about how you ripped your father's heart out of his chest — but the truth is, I’m struggling pretty hard to empathize with you. So I'm digging down, trying extra hard to find the tender places where you really live. Who are you beneath the labels? Beneath "prodigal," beneath “selfish,” beneath "sinner?”

"Dying of hunger." That's how your story describes your final days in that far-off country. When your costly adventure was over, when your funds ran dry, when your so-called friends abandoned you. There among the pigs, covered in filth, you finally realized who and what you were. "Dying of hunger." May I give you a new label? A new name? One I can relate to? Aren't you, at the very core, the Hungry One?

It was hunger, wasn't it, that first lured you away from a good life and a good father? A gluttonous hunger, maybe, but hunger still. For freedom? Self-expression? Novelty? Something in you — something wild and insistent — needed feeding.

But here’s the thing that knocks the breath out of me: your father, in his vast, unorthodox wisdom, understood. He didn’t hold you back. He didn’t decide what your journey should look like. He let you go.

What did he know that I refuse to know? That you couldn't return home without leaving first? That you couldn't taste resurrection without dying? That maybe lostness is part of the deal — the prelude to the most magnificent finding? Can it be that I, too, need to know such hunger — know it on the tongue, in the gut, like a fire in my bones — before I can savor the feast?

The father understood. What a remarkable thing that is — his deep and patient comprehension of how life and desire actually work. He respected the hunger that pulled you away. He knew a wiser, sharper hunger would bring you home.

|

Was it admirable? What you did? I don't know. But there is this: even though it cost you, even though it wounded your family, you honored your hunger. I can't speak to the rightness or wrongness of your decision, but maybe there is something in it that I should attend to. I usually ignore my hunger. When I can't ignore it, I hide, minimize, and vilify it. Is there a chance my hunger wants to point me to God?

Your journey ends in a passionate embrace. Unrestrained welcome, overflowing joy. Were you grateful? Were you indebted? Did you try extra hard in later years to earn the feast your father lavished on you? Or did you simply rest in his prodigal love, knowing it can never be earned? It seems your father didn't much care; he just wanted to feed and clothe you.

There's so little of your experience I can applaud. Despite my best attempts to reconcile my heart with yours, my envy remains. Your Father ran to welcome you. He cared for nothing in this world so much as having you safe and snug in his arms. No matter what the preachers say, this is not everyone's visceral experience. To hear we are loved is one thing. To feel ourselves embraced is another. You are fortunate. Do you know that? Something jealous in me wants to make sure you know it.

But something broken in me wants to reach you, too. To build bridges between your life and mine. What do you know that I know, too? I know what it's like to hunger. To hunger for life, for depth, for passion, for joy. I know what it's like to imagine an exotic Elsewhere, a more perfect nourishment miles away from my father's all-too-familiar table. I know lostness — the lostness of being small and sorry and stupid in a world too big and unwieldy to manipulate or control. I know what it's like to "come to myself" in the broken, impoverished places I create in my own heart. And I know what it’s like to feel shame — shame that I’ve disappointed everyone, shame that I’m damaged goods, shame that I’ll never, ever be enough to earn the love I crave.

I still don't like you. But maybe we're not so very different after all.

To the Boy Who Stayed:

I won't lie; my sympathies lie with you. Your story haunts me. Your resentments mirror mine. Whenever I think of you standing — appalled — outside your father's house, your brother's easy laughter ringing in your ears, I ache inside. I imagine you sore and sweat-stained after a day in the fields, longing to go inside for a shower, a meal, a bed. Longing for so many legitimate things — only to be thwarted by a robe, a ring, and a fatted calf. Not intended for you.

Theologians tell me I'm supposed to look at you and see self-righteousness, arrogance, and unholy spite. But I don't; I look at you and see pain.

I'm an oldest kid, too. I’m used to being responsible, staying home, and getting things done. By temperament, I'm careful, I like order, and I don't mind work. But I'm a stickler about fairness. I care about fairness a lot.

I am also, to be fair, a seether. I don't confront; I seethe. Just like you.

Tell me. How long did the bitterness fester? How many weeks, months, or years did you suffer in silence, mistaking restraint for righteousness? Did your father shrink in your eyes as your anger grew? Did every word he spoke, every request he made, every sigh he sighed, grate on your nerves? Did you lie in bed at night and wish you'd had the audacity to leave like your brother did?

Or maybe it was another kind of courage you lacked. The courage to cry? To plead? To confess a need so insatiable and so secret, it made you burn with shame?

What would have happened if you'd looked your father in the eye and said, "Yes. I know that all you have is mine. But it's not enough. I can't fathom why, but your "everything" is not enough for me. I can't find contentment. I can't make my way to love. Somehow, in your very Presence, I am lost."

|

I know these are terrifying things to admit to yourself, much less to say out loud. But what if you had said them? What if you had said, "Something in me is broken. Something in me can’t embrace or enjoy what's mine. Something in me doesn’t understand the joy that lives in giving myself away. Please help me. Wrap your arms around me. Hold me. I am full of hatred — for myself most of all. Please teach me how to love."

The challenge of your story — the challenge that tears at me — is that you have rightness on your side. You are right to call for justice. Right to ask why your brother's sins incurred no consequences. Right to ask why your own loyalty seems to count for so little.

You are right to find your father's version of love a bit much, a bit scandalous, a bit risky. Because it is. You've understood the point of your own story better than anyone. Yes, your brother squandered his inheritance. Perhaps, by hoarding and withholding, you've also squandered yours. But the real Prodigal in this story is your father, is he not? Over-the-top, undignified, and hair-raising in his love? Of course you're right to be appalled.

Here’s the thing: I don't know why your father never gave you a young goat. Or threw you and your friends a spontaneous party. I wish with all my heart he had; it makes me angry that he didn't. Was he waiting for you to ask? Were you, in turn, waiting for him to initiate? I know that mingy, self-protective mindset so well: "If I have to ask for it, then it doesn't count."

Maybe it does. Maybe there is something essential to be learned in the asking.

"We have to celebrate and rejoice." This is your father's final word to you as you stand out in the cold, your arms crossed, your fists clenched, your heart bleeding. Did you know, dutiful firstborn? Did you know you have to celebrate? Did you know that joy is a must in your father's house? That partying is a duty?

How astonishing that you lived within arm's reach of your father all these years, and never glimpsed the merriment that is at his core. "We have to celebrate and rejoice." He insists. But there you stand, lover of justice. One hundred percent right — and one hundred percent alone.

What will it take for you to lean into celebration as a teacher? To try out mercy as a balm? Can you believe it? Some lessons can only be learned as you laugh and dance. Some hearts will only be healed at the feast.

Here's your vindication, yours and mine: the power in this story is the older child’s. It’s yours. Your brother is inside; he's done breaking hearts for the time being. Now your father stands in the doorway, waiting for you. Waiting for you to stop being lost. Waiting for you to come home. Waiting for you to take hold at last of the inheritance that has always been yours.

Did you know that your choices are so powerful? You get to write this ending. You get to write this ending.

It's getting cold outside. The sun is setting, and the party beckons. What will you do, as the music grows sweeter? What will we choose, you and I?

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.