For Sunday November 4, 2018

All Saints Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 25:6-9

Psalm 24

Revelation 21:1-6a

John 11:32-44

As I sit down to write this essay, eleven people in a Pittsburgh synagogue are dead, gunned down just hours ago by an anti-Semitic man with an assault rifle. Over the past few days, at least a dozen prominent American Democrats, including two former presidents, have been the targets of assassination attempts. Even a cursory glance at international news headlines yields stories just as horrific: dozens dead in Eastern Syria; millions starving in Yemen; widespread killings, kidnappings, and communal violence in central Nigeria. In the midst of life, we are in death.

This week, Christians around the world celebrate All Souls and All Saints. In a world that fears, cheapens, and desecrates death, the Church invites God’s people to linger at the grave in grief, remembrance, gratitude, and hope. In a world that mistreats and abuses countless men, women, and children, the Church affirms the value of every single soul, every single life. In a world that privileges the individual, the Church honors the deep interconnectedness of God’s family across time, culture, history, and eternity. Yes, it’s true: in the midst of life, we are in death. But All Souls and All Saints remind us of a deeper truth: in the midst of death, we are promised life.

Our Gospel reading for All Saints Sunday — the story of the raising of Lazarus — is one of the most dramatic and difficult in Scripture, and I’ll confess at the outset that I don’t understand it. I don’t understand why Jesus dawdles when he first receives word of Lazarus’s illness. I don’t understand why he tells his disciples that Lazarus is “asleep” rather than dead. I don’t understand why he chooses to bring Lazarus back at all — does a man who’s been dead for four days even want to come back? And I definitely don’t understand why Lazarus virtually disappears from the Gospel narrative once his grave clothes fall off. Why is he never heard from again?

|

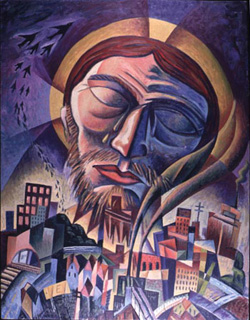

In many ways, the story is shrouded in mystery. But today, this week, now, I cling to the two words in the narrative I do understand: “Jesus wept.” For me, this is the heart of the story, that grief takes hold of God and breaks him down. That Jesus — the most accurate revelation of the divine we will ever have — stands at the grave of his friend and cries.

It has taken me a long time, though, to appreciate Jesus’s tears in this story. When I was a little girl, I didn’t understand why Jesus cried when he knew that Lazarus was about to come back to life. Why mourn when joy is minutes away? As a young adult struggling with my faith, I didn’t understand why Jesus cried after intentionally staying away from Bethany during Lazarus’s illness. Like some of the onlookers in the story, I responded to Jesus’s grief with cynicism and contempt: “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind have kept this man from dying?”

Over time, though, I’ve come to cherish Jesus’s tears, perhaps even more than I cherish the miracle that follows them. Here are some of the reasons why:

When Jesus weeps, he legitimizes human grief. His brokenness in the face of Mary’s sorrow negates all forms of Christian triumphalism that leave no room for lament. Yes, resurrection is around the corner, but in this story, the promise of joy doesn’t cancel out the essential work of grief. When Jesus cries, he assures Mary not only that her beloved brother is worth crying for, but also that she is worth crying with. Through his tears, Jesus calls all of us into the holy vocation of empathy.

|

When Jesus cries, he honors the complexity of our gains and losses, our sorrows and joys. Raising Lazarus would not bring back the past. It would not cancel out the pain of his final illness, the memory of saying goodbye to a life he loved, or the gaping absence his sisters felt when he died. Whatever joys awaited his family in the future would be layered joys. Joys shaped by the sorrows, fears, and losses they’d just endured. In Lazarus’s case, his future would be nothing like his past. Forever afterwards, he’d be known in his village as the One Who Returned. Perhaps that bizarre fact would make him a hero. Perhaps it would make him a pariah. Whatever the case, Jesus’s tears honor the reality of human change: he grieves because things will never be the same again.

When Jesus cries, he honors the nuances of faith. At no point does he expect piety to be disembodied or sanitized. He recognizes that all expressions of belief and trust come with emotional baggage. Martha expresses deep resentment and anger at Jesus’s delay, and in the next breath voices her trust in his power. Mary blames Jesus for Lazarus’s death, but she does so on her knees, in a posture of belief and submission. Likewise, Jesus’s face is wet with tears when he prays to God and resurrects his friend. This is what real faith looks like; it embraces rather than vilifies the full spectrum of human psychology.

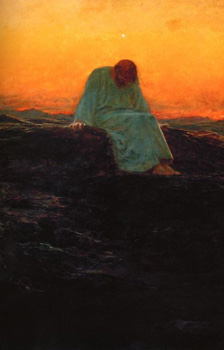

When Jesus weeps, he acknowledges his own mortality. In John’s Gospel, the raising of Lazarus is the precipitating event that leads to Jesus’s own arrest and crucifixion. When word spreads about the miracle in Bethany, the authorities decide that enough is enough; Jesus must be stopped. So essentially, Jesus trades his life for his friend’s. Given this fact, I imagine that Jesus’s tears are an expression of grief over his own pending death. He knows that the end is imminent, he knows that his time with his friends is almost over, he knows that it’s nearly time to say goodbye to the lakes and skies and hills and stars he loves. In crying, he asserts powerfully that it is okay to yearn for life. It’s okay to feel a sense of wrongness and injustice in the face of death. It is okay to mourn the loss of vitality, of intimacy, of longevity. It is okay to love and cherish the gift of life here and now.

|

And finally, when Jesus weeps, he shows us that sorrow is a powerful catalyst for change. In the story of Lazarus, it is shared lament that leads to transformation. It’s because Jesus experiences the devastation of death that he recognizes the immediate need to restore life. It is his shattering that leads to resurrection. Perhaps Jesus’s tears can provoke us in similar ways. What breaks our hearts? What splits us open in sorrow? What enrages us to the point of breakdown? Can we mobilize into those very spaces? Can we work for transformation in our places of devastation? Can our sorrow lead us to justice?

This week, as we gather to honor All Souls and All Saints, as we take time to remember, to mourn, and to celebrate those who have gone on before us, I hope that Jesus’s tears can be our guide. I hope his honest expression of sorrow will give us the permisson, the company, and the impetus we need, not only to do the work of grief and healing, but to move with powerful compassion into a world that sorely needs our empathy and our love. Yes, we are in death, but we serve a God who calls us to life. Our journey is not to the grave, but through it. The Lord who weeps is also the Lord who resurrects. So we mourn in hope.

Image credits: (1) The Value of Sparrows; (2) FineArtAmerica.com; and (3) Pinterest.com.