For Sunday June 24, 2018

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1st Samuel 17: 1a, 4-11, 19-23, 32-49

Psalm 9:9-20

2 Corinthians 6:1-13

Mark 4:35-41

The Bible contains its fair share of challenging questions, but this week’s Gospel reading is particularly full of zingers. The lection is from Mark's Gospel, and the miracle it describes — Jesus' calming of a stormy sea — is one of the most dramatic in the New Testament. The setting is the Sea of Galilee, a body of water 680 feet below sea level, surrounded by hills, and prone to sudden, violent windstorms. The time is evening.

After a long day spent preaching to the multitudes, Jesus is curled up at the stern of a boat, sleeping soundly as his disciples steer the vessel. All at once, the winds pick up, huge waves lash the boat, and the disciples, seasoned fishermen though they are, fear for their lives.

In a desperation bordering on fury, they rouse the still-sleeping Jesus: "Teacher, don't you care that we are drowning?"

Jesus says nothing. But he stands up, rebukes the wind, and calms the sea. Then he turns to his stunned disciples and responds to their question with a couple of his own: "Why are you afraid? Do you still have no faith?”

The disciples don’t answer him. Intead, Mark writes, they "fear a great fear." "Who is this man?" they finally ask each other. "Even the wind and waves obey him!"

Don’t you care? Why are you afraid? Do you still have no faith? Who is this man? Four questions. I call them zingers because they challenge the way I practice my faith. I also call them zingers because they drudge up old religious muck in my heart — muck that prevents my crossing over from fear, suspicion, and certainty to courage, trust, and curiosity.

|

|

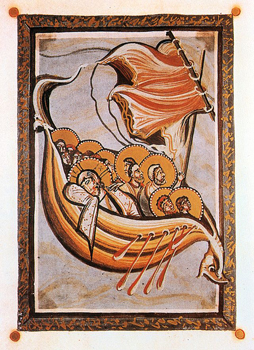

Calming the Storm — Hitda Codex, after 1000.

|

Like some of you, I grew up with near-lethal doses of a “Fear not!” Christianity — a Christianity of perpetual triumph and victory. It was a Christianity of Happily Ever After or Else. A Christianity that left no room for fear. If you're not familiar with this brand of religion, it sounds a bit like this:

"Fear Not" appears in the Bible more often than any other imperative. Which means it is a commandment. Which means fear is a sin.

And like this: "Perfect love casts out fear." If you're afraid, it means you're not leaning into the perfect love of Jesus.

And like this: "For God has not given us the spirit of fear; but of power, and of love, and of a sound mind." Which means that fear is an aberration. It indicates unsoundness of mind, a brokenness that is not of God.

I wish I were exaggerating, but I'm not; I grew up hearing these "devout" responses to fear all the time, and they messed me up for years. Instead of inspiring courage in me, they coated my ever-present fear in shame, guilt, and a deep sense of inadequacy. So when I read this week’s lectionary, and see Jesus asking his storm-soaked disciples why they’re afraid, all my old insecurities and defenses go up.

Why are the disciples afraid? Um, isn’t it obvious? They're afraid because they aren't keen on drowning. And because gigantic waves are scary. And because God created human beings with a necessary capacity to feel fear. And because sometimes our genetic makeups and/or our early childhood experiences pre-dispose us to crippling anxiety and panic.

Honestly, what a stupid question! If we extend the meaning of "drowning" to include all the ways in which we human beings find ourselves in over our heads in this world, then Jesus' question sounds not only ludicrous, but cruel. Of course we feel afraid as we face climate change and school shootings. Of course we feel afraid when broken marriages, sick children, unfriendly neighbors, grinding jobs, and financial uncertainty threaten our lives. Of course we feel afraid when biology or trauma betray us into anxiety, panic, and depression.

And yet. Is it really a stupid question? What if its meaning changes dramatically when we read it through the lens of the first question — the one the disciples ask Jesus as the waves threaten to capsize their boat? “Teacher, don’t you care that we are drowning?”

|

|

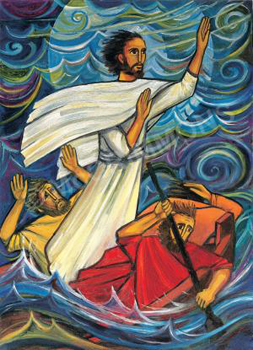

Jesus Calming the Storm — Irish Illuminated Manuscript, 11th Century.

|

I’ve had to read this Gospel story many times to see a helpful connection between the disciples’ question and Jesus’s, but I see now that a connection is crucial. What if Jesus’s question about fear has nothing to do with the sea, the wind, and the killer waves? What if it has to do only with the disciples’ relationship with him?

Notice the first place the disciples’ fear takes them. They have every right to be afraid when the storm breaks; feeling scared in the face of danger is not the problem. The problem is that their fear does not lead them to lean harder on Jesus, or to seek comfort in his presence. Rather, it leads them straight to suspicion, distrust, and accusation: “Teacher, don’t you care that we are drowning?”

What is their underlying assumption? That Jesus must not care. If he cared, he wouldn’t be sleeping. If he cared, they wouldn’t have to seek him out or wait for him. If he cared, he’d hurry up. If he cared, they would be safe.

Needless to say, these responses cut right through me; I recognize them so well. Like the disciples, I am quick to assume the worst about Jesus when the going gets rough. When I face fearsome circumstances, my go-to position is not trust; it's suspicion. In my fear, I conjure up a God who is stony-faced, implacable, and loveless. A God to whom I am expendable. What should be a rich, vibrant, and multifaceted relationship between my heart and God's becomes instead purely consumerist and transactional: Okay, Jesus, prove that you care about me by fixing my circumstances. I’ll do A (trust and love you) if you’ll do B (protect and save me).

One of the odd things about this lection is that Mark surrounds it with a perplexing set of contrasts. In the chapters preceding the calming of the sea story, Jesus describes the kingdom of God as small, secretive, and quiet. The kingdom is like a mustard seed, so tiny it's almost invisible. The kingdom of God is like a sower scattering seeds — seeds so vulnerable, they're often snatched by birds or choked by weeds. The kingdom of God is like a farmer whose seeds defy manipulation — they grow if and when they please.

In the chapters that follow, however, Jesus manifests a kingdom of dramatic, supernatural power. He casts out demons, raises a little girl from the dead, heals a hemorrhaging woman, feeds five thousand people with a few handfuls of bread and fish, and walks on water.

To truly trust Jesus, then, is to hold two pictures of the kingdom in productive tension. Yes, sometimes Jesus demonstrates his power in miraculous, Technicolor ways; we're not wrong to hope for such demonstrations. At other times, though, we need to trust that his Incarnation — his quiet, abiding presence in our lives — is enough for the cirumstances we face. Sometimes, Jesus' power is paradoxical; it comes to us in what looks like vulnerability, like weakness, like “sleep.” The hiddenness of God, in other words, is simply that. Hiddenness, not absence.

|

|

Pentecost Icon.

|

When Jesus asks the disciples why they’re afraid, what he’s really asking is: why are you afraid of me? Why do you still not trust that I love you, that I am with you, for you, in you, and around you? After all this time, why do you suspect my heart, my intentions, my good will?

Thankfully, the disciples do “cross over” in this story. Not just from one shore to another, but from deep distrust to trembling awe. The question that ends the lection is a question grounded in wonder, in life-giving curiosity: “Who is this man?”

Before the storm breaks, the disciples think they have Jesus pegged. They think they know what to expect of him. But they're wrong. He is powerful, yes. But he is also far more restrained, mysterious, unpredictable, and hidden than they have imagined.

I walk away from this story convinced that fear isn't always an enemy. No human emotion, created by God, is always an enemy. Flattening out our emotions in order to declare spiritual victory is not faithfulness; it's lying.

But when our fear leads us to distrust God and suspect each other, when it replaces spiritual curiosity with a dull and cynical certitude, then it’s time to bring our fear to Jesus and ask him to transform it. Our work is always to cross over from fear to awe, from suspicion to trust, from certainty to wonder. No matter how high the storm waves in our lives, may we always rest in God’s presence as we cross to the other side.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Pinterest.com; and (3) ArtsyWanderer.WordPress.com.