For Sunday August 13, 2017

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 37:1–4, 12–28 or 1 Kings 19:9–18

Psalm 105:1–6, 16–22, 45b or Psalm 85:8–13

Romans 10:5–15

Matthew 14:22–33

In his book Not in God's Name (2015), Rabbi Jonathan Sacks locates the origins of religious violence in sibling rivalry and mimetic desire. Sibling rivalry, he says, is "the most primal form of violence," and "the dominant theme of the book of Genesis."

In sibling rivalry, we desire what others have, we become rivals for it, and then we fight to get it in what we wrongly think is a zero sum game. The stories in Genesis are familiar to those who know their Bibles, and Sacks offers interpretations in which sibling rivalry is revealed for what it is and then subverted.

With Isaac and Ishmael we learn that "God chooses (Isaac), but he doesn't reject (Ishmael)." The story of Jacob and Esau is "the refutation of sibling rivalry in the Bible." Recall how Jacob returned the blessing that he stole from his blind father Isaac to Esau. Rachel and Leah exemplify the "rejection of rejection." Sibling rivalry is natural, says Sacks, but it's not inevitable.

That brings us to the reading this week about Joseph. The rivalry between Joseph and his brothers who tried to kill him takes up a third of the book of Genesis. In the end, the victim forgives and the perpetrators repent.

The Joseph story in Genesis 37–50 begins when he is seventeen and ends with his death in Egypt at the age of a hundred and ten. That's ninety-three long years exiled from his family. The story features three sets of two dreams, all six of which are construed as divine messages.

|

|

Joseph's servants fill his brothers' sacks with wheat, late 15th century illuminated mss. by Raphael de Mercatelli.

|

Joseph had two dreams as a teenager, one about sheaves of grain and another about the stars in the sky. Both of them foretold of sibling rivalry — that he would rule over his older brothers.

The next four dreams feature Joseph as the interpreter of dreams, although he insists that it's not him but God who gives the interpretation. He deciphers a good dream by the cup bearer and a very bad dream by the baker. He then interprets Pharaoh's two dreams about future years of feast and famine.

These six dreams turned Joseph's life into a living nightmare. Some of the deepest hurts that we experience come from our own families, and often through no fault of our own. Such was the case with Joseph.

His brothers resented their father's favoritism, epitomized in his "coat of many colors" that privileged him above them. So they sold Joseph to Midianite merchants (slave traders?), who in turn sold him to an Egyptian official named Potiphar. This began thirteen years of slavery and imprisonment for Joseph (37:2–3, 41:46).

He was later tempted and falsely accused of rape by Potiphar's wife. Languishing in prison for crimes he didn't commit, he was forgotten by the cup bearer, who had gained his own freedom thanks to Joseph.

As history unfolded, though, roles were reversed. Joseph's brothers and family became beggars in a famine, whereas he was elevated to Pharaoh's second-in-command. When their fratricide was exposed, the brothers rightly expected retaliation. But in contrast to his brothers who tried to kill him out of jealousy, Joseph forgave his brothers out of a sense of God's providence.

It's no wonder that this week's Psalm 105:16–22 honors Joseph. He believed that God had a providential purpose in the wrongs that he had suffered, namely, to preserve a remnant that would fulfill the promise to Abraham. "Don't be afraid," Joseph assured his brothers. "Am I in the place of God? You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good" (Genesis 50:20).

At least four times Joseph reassures his nervous brothers that "it was not you who sent me to Egypt, but God" (Genesis 45:5, 7, 8, 9). It's a radical idea, that nothing that I experience happens without divine design. In the words of the song Like a River Glorious by Frances Ridley Havergal, "Every joy or sorrow / Falleth from above / Traced upon our dial / By the Sun of love."

The Joseph story shows how God uses our worst sins, sufferings and failures in redemptive ways. Many have observed how God brings good out of evil. St. Augustine wrote, “God judged it better to bring good out of evil than to allow no evil to exist.”

The contemporary Frederick Buechner writes, “sin itself can be a means of grace.”

Julian of Norwich (1342–1414) once said that “sin will be no shame but an honor.”

Anthony deMello writes that “repentance reaches fullness when you are brought to gratitude for your sins.”

|

|

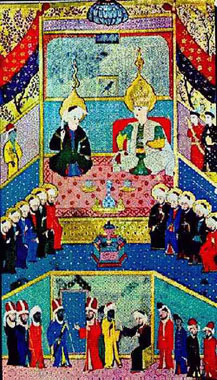

Joseph with his father Jacob and brothers in Egypt from the 16th century illuminated mss. Zubdat-al Tawarikh in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul, dedicated to Sultan Murad III in 1583.

|

Finally, Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274) gave us the startling phrase “O felix culpa!” in reference to the fall of Adam. “O fortunate crime!” The fall of Adam with all its catastrophic consequences triggered something far better and greater — the incarnation, life, death and resurrection of Jesus.

This is dangerous territory. There's a thin and mysterious line between honoring God's providence and calling evil good. We should also be wary of enabling or excusing bad family behaviors instead of dealing with them. Nor should we ever turn a blind eye to injustice as if it didn't matter.

Nevertheless, Joseph moves beyond these legitimate concerns and discerns a larger purpose of good in the evil that he suffered. Perhaps this is something that one can claim for yourself but should never presume for another.

I like how the Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann (b. 1933) acknowledges the evil in the world, but also expresses faith in God's greater providence. Consider his poem "Dreams and Nightmares" from his book Prayers for a Privileged People (2008):

Last night as I lay sleeping,

I had a dream so fair…

I dreamed of the Holy City, well ordered and just.

I dreamed of a garden of paradise, well-being all around and a good water supply.

I dreamed of disarmament and forgiveness, and caring embrace for all those in need.

I dreamed of a coming time when death is no more.Last night as I lay sleeping…

I had a nightmare of sins unforgiven.

I had a nightmare of land mines still exploding and maimed children.

I had a nightmare of the poor left unloved,

of the homeless left unnoticed,

of the dead left ungrieved.

I had a nightmare of quarrels and rages and wars great and small.When I awoke, I found you still to be God,

presiding over the day and night

with serene sovereignty,

for dark and light are both alike to you.At the break of day we submit to you

our best dreams

and our worst nightmares,

asking that your healing mercy should override threats,

that your goodness will make our

nightmares less toxic

and our dreams more real.Thank you for visiting us with newness

that overrides what is old and deathly among us.

Come among us this day; dream us toward

health and peace,

we pray in the real name of Jesus

who exposes our fantasies.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; and (2) Wikipedia.org.