There is No Them

by Dan Clendenin

For Sunday February 1, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Deuteronomy 18:15–20

Psalm 111

1 Corinthians 8:1–13

Mark 1:21–28

I recently read two books by very different authors that both make the same provocative point. One was by a Muslim teenager, the other was by an evangelical pastor.

Both authors struggle with what Deuteronomy 18 for this week calls the "detestable practices" of the pagan nations — outrageous things like child sacrifice. Only in this case, the authors lament the "detestable practices" not of other religions but of their own people.

Brian Zahnd's book, A Farewell to Mars (2014), is a good example of why it's misleading to make dismissive generalizations about evangelicalism, which for a long time has been a more complex and interesting movement than its detractors have acknowledged. Zahnd founded the Word of Life Church in 1981. Today it has a 2,500-seat sanctuary that sits in the middle of a cornfield thirty minutes north of Kansas City. Those demographics sound like a perfect set up, but Zahnd breaks the stereotypes.

|

Muslim prayer. |

Zahnd's book describes how he repented from his "worst sin ever." I'm sure he would resonate with the language of Deuteronomy 18 about the "detestable practices" of God's people. No, he didn't embezzle money or sleep with his secretary. In his description, it was far worse than that.

It took fifteen years, but in 2006 he had an epiphany of how back in 1991 he was a cheerleader for America's first Iraqi war called Operation Desert Storm. He describes how he and his friends ordered pizza and watched the war on television, how they hooped and hollered, how he prayed war prayers and preached war sermons to his congregation. And they loved it.

"How I reached the point where I could weep over war and repent of any fascination with it is part of what this book is about — it's the story of how I left the paradigms of nationalism, militarism, and violence as a legitimate means of shaping the world to embrace the radical alternative of the gospel of peace."

Today Zahnd repudiates the detestable practices of a privatized piety that is merely spiritual and only for a future in heaven. He's no longer a "chaplain" to the state who offers "innocuous invocations" for a Constantinian Christianity. He's shocked to remember how he promoted sacred violence against fellow human beings.

Having bid farewell to the Roman god of war (Mars), the last chapter of Zahnd's book is one sentence. It casts a positive vision for the people of God: "There is no them; there is only us."

|

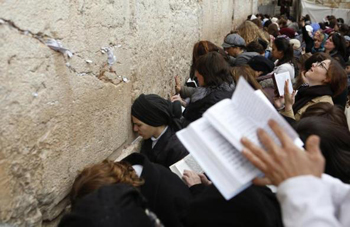

Jerusalem's western wall. |

The Muslim teenager Malala Yousafzai arrives at the same point in a different way. She tells her story in her autobiography I am Malala (2013). The book describes how Malala turned her personal tragedy into a global mission. Like Zahnd's repentance of the practices of some Christians, Malala repudiates the "detestable practices" of the Taliban in her beloved Pakistan.

Malala was eleven when the Taliban took over her Swat Valley in northwestern Pakistan in 2008. They bombed everything — power stations, a ski lift, hotels, funerals, and over 400 schools. They conducted public whippings and hangings. They beheaded over 1400 fellow Muslims. Police were so terrified of being murdered that they took out newspaper advertisements to announce that they had quit the force. The Pakistani army eventually rooted them out, or so they said, but the troubles continued.

Malala's father received death threats, which wasn't a surprise given that he was an outspoken political activist who had founded a major school that educated girls. He even kept a copy of Martin Niemoeller's famous prayer in his pocket ("First they came…"). At night, after everyone was asleep, Malala would get up and make sure all the doors and windows in the house were locked.

By this same time, at age eleven, young Malala had emulated her brave father. She wrote a diary for the BBC Urdu station under a pen name that described life under the Taliban. She gave interviews on Pakistani national television. The NY Times did a documentary about her. She had won numerous academic awards. She knew she wanted to be a politician.

When she was fifteen, on October 9, 2012, a Taliban gunman fired three shots at point blank range at Malala as she rode home on her school bus. One shot hit her, and the other two wounded her two class mates. After a miraculous recovery in England, the attempted murder catapulted her onto the stage of a global campaign. On her sixteenth birthday she spoke at the United Nations. In October 2014, at the age of seventeen, she became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

On those scary nights when she double checked all the doors and windows, Malala also prayed. "At night I used to pray a lot. I'd pray to God, 'Bless us. First our father and family, then our street, then our whole 'mohalla' (district), then all Swat.' Then I'd say, 'No, all Muslims.' Then, 'No, not just Muslims; bless all human brings.'"

Today Malala is an outspoken critic of all forms of "detestable practices" done against all people, and in particular against women and girls. Stated positively, she's an advocate for the inherent dignity of "all human beings." Her journey from the isolated Swat Valley in Pakistan has taken her to the same place as Brian Zahnd: there is no them; there is only us.

The gospel for this week describes how "the people were amazed at Jesus's teaching, because he taught them as one who had authority, not as the teachers of the law." What was so amazing, so new, so authoritative about Jesus?

Jesus brought healing and wholeness in all he said and did. He drove out evil spirits. He embraced everyone and excluded no one.

There is no them; there is only us, and so with Malala we work and pray for God's blessing on every human being.

|

Pope Francis foot washing. |

For further reflection:

* Tzvetan Todorov, The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other (1982).

* Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (1996).

* Martin Niemoeller (1892–1984).

First they came for the Communists,

- but I was not a communist so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Socialists and the Trade Unionists,

- but I was neither, so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Jews,

- but I was not a Jew so I did not speak out.

And when they came for me, there was no one left to speak out for me.

This poem is ascribed to the German pastor Martin Niemoeller, who protested Hitler's anti-semite measures in person to the fuehrer, was eventually arrested, and then imprisoned for eight years at Sachsenhausen and Dachau (1937–1945). He once confessed, "It took me a long time to learn that God is not the enemy of my enemies. He is not even the enemy of his enemies." The poem describes the passivity of German intellectuals as the Nazi's purged group after group of targeted people. The poem comes in many slightly different versions, and its exact origin is the subject of debate.

Image credits: (1) Asianews.it; (2) Reuters.com; and (3) Patheos.com.