Can a Good Christian Be a Good Citizen?

The Reign of Christ the King

For Sunday November 22, 2009

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Samuel 23:1–7 or Daniel 7:9–10, 13–14

Psalm 132:1–12, (13–18) or Psalm 93

Revelation 1:4b–8

John 18:33–37

This very last Sunday of the lectionary year celebrates "Christ the King." Such explicitly political language to describe a religious leader raises a provocative question: can a good Christian be a good citizen?

The gospel this week records the most dramatic political confrontation in all of Scripture — Pontius Pilate's interrogation of Jesus in the praetorium, his three-fold declaration that he found him innocent, then his death sentence verdict to pacify the mob, mock the Jews, and protect his job. John's gospel makes it crystal clear that the passion narrative in general and the trial before Pilate in particular were specifically political rather than religious crises. Jesus's trial and Roman execution epitomized a clash between two kings and two kingdoms, and the allegiance that they both solicit from us.

|

Pontius Pilate, by Giotto, 1305. |

The Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan (1923–2006) observes a fascinating paradox about the Christian confession: "One of the many historical ironies of the Christian message is that of all the famous ancient Romans — Julius Caesar or Cicero or Vergil — none has achieved even nearly the universal name recognition of an otherwise obscure provincial gauleiter named Pontius Pilate, who has the distinction — which he shares with, of all people, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and with no other human creature — of having his name recited every day all over the world in the Nicene Creed (as well as in the Apostles' Creed): 'crucified on our behalf under Pontius Pilate.'"

Pelikan also notes that just as pagans accused the earliest followers of Jesus of cannibalism because of their eucharistic practices, they also accused them of sedition because of the overt political implications of their confession of a "kingdom of God" and a "citizenship in heaven" (Philippians 3:20). [Footnote, Jaroslav Pelikan, Acts (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2006), p. 266.]

The birth of Jesus signaled that God would "bring down rulers from their thrones" (Luke 1:52). In Mark's gospel the very first words that Jesus spoke announced that "the kingdom of God is at hand" (1:15). John's gospel takes us to the death of Jesus, and the political theme is the same. Jesus was dragged to the Roman governor's palace for three reasons, all political: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King" (Luke 23:1–2). In short, Jesus died as a political criminal.

Pilate met the angry mob outside the praetorium, then grilled Jesus alone back inside. "Are you the king of the Jews?"

"My kingdom is not of this world," Jesus replied. "My kingdom is from another place."

"You are a king, then!" mocked Pilate.

"Yes, you are right in saying that I am a king."

Pilate went back outside, declared that Jesus was innocent, then had his soldiers beat, flog, and humiliate him with purple robes and a crown of thorns befitting a man whom he miscalculated was a political poser: "Hail, O king of the Jews!"

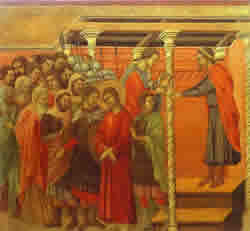

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Pilate Washing His Hands, 1308–11. |

Back outside, the mob hounded Pilate: "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar." Pilate thus found himself sandwiched between angering the mob and betraying his emperor.

He caved in: "Here is your king. Shall I crucify your king?"

"We have no king but Caesar!"

When Pilate crucified Jesus, he insulted the Jews one last time by fastening a notice to the cross, written in Aramaic, Latin, and Greek, that he knew they would find repugnant: "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." They objected, of course: "Don't write 'The king of the Jews,' but that this man claimed to be king of the Jews."

It was too late: "What I have written, I have written," said Pilate. To be sure, with his mockery of the Jews he wrote much more than he ever could have known or imagined (John 18:28–19:22).

Charges of political sedition dogged the first Christians twenty years later. The Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus (55–117) describe the persecution of Christians under the Roman Emperor Nero. On June 18, AD 64, a fire broke out in Rome that burned for ten days and destroyed much of the city. Most people suspected that Nero himself started the fire, ostensibly to rebuild Rome, so to allay the rumors Nero blamed the Christians. Since these Christians were “hated for their abominations” anyway, writes Tacitus, Nero “punished them with refined cruelty.” Similarly, in his work Life of Nero the Roman biographer Suetonius (75–160) tells us that under Nero's reign “punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a set of men adhering to a novel and mischievous superstition.”

For their part, the early believers used two graphic images to picture the Roman state. Rome was a beastly dragon who stood in front of a woman giving birth in order to "devour" the newborn son who would rule all the nations. Rome was also a whore "drunk with the blood of the saints" (see Revelation 11-13, 17).

|

Pilate washes his hands, The Liege Psalm book, Belgium, 13th century. |

In his little book The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (1984), the historian Robert Louis Wilken demonstrates the broad and deep antipathy that developed in the first five centuries toward the Christian movement. For about a hundred years the emergent Christian movement was invisible to most people in the Roman empire. But across the decades Christians earned a reputation as an alternate and anti-social community that existed on the margins of the state.

Christians were thought to be fanatical, seditious, obstinate, and defiant. Tacitus called them "haters of mankind." They scorned long-held Roman religious traditions. Many of their adherents came from the lower classes and seemed gullible. They refused military service, and met for clandestine rites rumored to include cannibalism, ritual murder, and incest. All of which is to say, in the words of one early critic, the Christians "do not understand their civic duty." In his view they actively undermined society with their indifference to civic affairs. Some critics even blamed Christians for the fall of Rome.

When Jesus insisted that his kingdom was "not of this world" he did not mean that it was merely spiritual, or relegated to a future age beyond history or in heaven. Far from it, as his detractors rightly surmised. In John's dialogue above Jesus's enemies rightly concluded that if Jesus was a king, a Lord, and a ruler, he clearly usurped and upstaged Caesar as Lord. Their two kingdoms clashed.

In its simplest terms, the kingdom of God that Jesus announced and embodied is what life would be like on earth, here and now, if God were king and the rulers of this world were not (Borg, Crossan). Imagine if God ruled the nations, and not Obama, Medvedev, Kim Jong-il, Mugabe, or Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Every aspect of personal and communal life would experience a radical reversal. The political, economic, and social subversions would be almost endless—peace-making instead of war mongering, liberation not exploitation, sacrifice rather than subjugation, mercy not vengeance, care for the vulnerable instead of privileges for the powerful, generosity instead of greed, humility rather than hubris, embrace rather than exclusion, etc. The ancient Hebrews had a marvelous word for this, shalom, or human well-being.

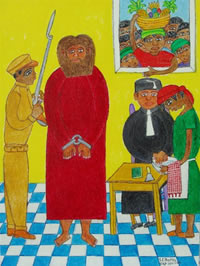

|

Pontius Pilate by Seymour E. Bottex, Haitian Master. |

In apocalyptic dreams and visions, this week's Old Testament reading from the prophet Daniel traces the rise and fall of the greatest political kingdoms in human history — Babylon, Persia under Cyrus the Great, Greece under Alexander the Great, and then Rome. Above and beyond them all, though, Daniel foretells of a king and a kingdom that is not ethnically, spatially or temporally limited; it is "an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and will never be destroyed." Rather than an ethnocentric kingdom limited to one land and one people, this kingdom welcomes "all peoples, nations and men of every language" to worship the one true "ruler of the kings of the earth" (Daniel 7:14–15; Revelation 1:5).

The Lord's Prayer, then, just might be the most subversive of all political acts: "Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven." People who live and pray this way have a very different agenda than Caesar's, whether Republican or Democrat, whether capitalist, socialist or communist, whether democratic or theocratic, for they have entered a kingdom, pledged their allegiance to a ruler, and submitted to the reign of Christ the King.

For further reflection

* Why has Christianity embraced political power down through the ages?

* In what sense can prayer be political or subversive?

* What did Jesus mean when he said "render to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's?"

* What did Paul mean when he told believers to "submit to the governing authorities?" Remember that Paul lived under Nero.

* Consider Peter: "Fear God, honor the king."

* Cf. John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus (1994).

Image credits: (1) Bill Petro blog; (2) Olga's Gallery; (3) Friends-Partners.org; and (4) Arte del Pueblo.