The Power of the Dogs:

When Trouble is Near

For Sunday May 14 , 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 8:26–40

Psalm 22:25–31

1 John 4:7–21

John 15:1–8

|

Acholi people in Uganda. |

Abandoned by God?

That might not sound like a very pious thought, but it sure is a common experience. The slings and arrows of life can give one pause. A reader of this webzine recently wrote to me about his battle with the final stages of AIDS. My daughter has a teenage buddy who was just diagnosed with a malignant tumor; if the aggressive chemotherapy is not successful doctors will have to amputate her arm. A few weeks ago a friend received the phone call that every parent dreads—a child was involved in an alcohol-related fatal car accident. Beyond these personal pains the daily news reminds us of global suffering; there are now reports of yet another genocide, this one against the Acholi people in northern Uganda where mortality rates are three times higher than in Darfur.

Faced with such public and private hells, some people jettison faith altogether. The Oxford zoologist Richard Dawkins derides religion as "an indulgence in irrationality" (cf. his forthcoming book The God Delusion). Philosopher Daniel Dennett of Tufts University reduces faith to a primitive impulse rooted in our evolutionary biology (Breaking the Spell, 2006). Atheism can feel brave and bold, but not many people have adopted its minority report. Repudiating faith altogether does little to solve the problems of human suffering, and might even lead to nihilism. Few people find atheism spiritually and emotionally fulfilling. Feeling abandoned by God is bad enough, but abandonment to your own solitary self, fully alone in the world, is worse.

Despite the pain and suffering that we experience, the vast majority of people maintain their belief in God. Truth should not be determined by majority opinion (sometimes the tiny minority is right), but I think that this hints at something. A few Sundays ago I noticed in the New York Times that for hardcover nonfiction books ten of the top twenty-five bestsellers dealt with religion in general or Christianity in particular. At one level I think the reading public's interest in religion illustrates our curiosity about history, culture, and politics, but scratch a little deeper and I think you discover a palpable longing for assurance in a world where "trouble is near" and "there is no one to help." (Psalm 22:11).

|

Psalm 22:1 by Linda Henke. www.lindahenke.com |

Psalm 22 for this week makes for painful reading. The Hebrew poet praises God, and pours out his heart to him, but he also argues with God. His candor is so much more authentic than the pious cliches that we sometimes use to mask our pain. The Psalmist complains that God is not only remote but silent. His prayers go unanswered. Acquaintances ridicule and mock his faith, leading to social isolation: "He trusts in the Lord; let the Lord rescue him!" They (wrongly) regarded his misfortunes as proof of divine displeasure. As if recounting a bizarre nightmare, he imagines raging bulls, roaring lions, and wild oxen attacking him. Threatened by "the power of the dogs" (22:20), he loses his composure: "My heart has turned to wax; it has melted away within me." In his state of weakness, confusion, and vulnerability, his life spins out of control. He can no longer control his destiny, and compares himself to "those who cannot keep themselves alive." I can only try to imagine what an Acholi person might feel when reading such poetry.

The Psalmist reminds us just how much God prefers heartfelt authenticity to superficial religiosity. The Scriptures encourage us not to suppress or candy coat our feelings of abandonment. They do not discourage our cries of dereliction, our sense of divine desertion, but in fact give them voice. In his poem Affliction (IV) the poet and pastor George Herbert (1593–1633) captures this paradox of resilient faith in the midst of deep anguish.

Broken in pieces all asunder,

Lord, hunt me not,

A thing forgot,

Once a poor creature, now a wonder,

A wonder tortur’d in the space

Betwixt this world and that of grace.My thoughts are all a case of knives,

Wounding my heart

With scatter’d smart,

As wat’ring pots give flowers their lives.

Nothing their fury can control,

While they do wound and prick my soul.All my attendants are at strife,

Quitting their place

Unto my face:

Nothing performs the task of life:

The elements are let loose to fight,

And while I live, try out their right.Oh help, my God! let not their plot

Kill them and me,

And also thee,

Who art my life: dissolve the knot,

As the sun scatters by his light

All the rebellions of the night.Then shall those powers, which work for grief,

Enter thy pay,

And day by day

Labour thy praise, and my relief;

With care and courage building me,

Till I reach heav’n, and much more, thee.

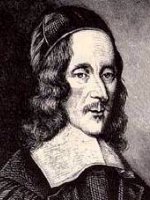

|

George Herbert. |

Born to privilege, Herbert experienced his own brokenness, and a result he demonstrated unusual compassion for the human condition. He was only three when his father died. Elected to Parliament, he anticipated a distinguished career in politics and public service. At the age of thirty-six he shocked his friends when he became the rector at Bemerton, a small village near Salisbury, where he spent the rest of his short life before dying of tuberculosis at age forty. In Bemerton he preached, wrote poetry, served the pastoral needs of his people with loving distinction, cared for the poor, and even helped to rebuild the church using his own resources. None of Herbert's poems had been published when he died, but upon his deathbed he gave them to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, asking them to be published only if they might help “any dejected poor soul.” His “little book,” as he called it, contained “a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed betwixt God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus my Master: in whose service I have found perfect freedom.”

Herbert could write like this because he interpreted his human brokenness in light of divine compassion. Like the Psalmist he believed that ultimately God "has not despised or disdained the suffering of the afflicted one; he has not hidden his face from him but has listened to his cry for help." Jesus himself screamed the prayer of Psalm 22 when he hung from the cross (Mark 15:34). In so doing, he modeled for us what Lawrence Cunningham has called "the primordial truth of the entire biblical tradition. Negatively put, we are not condemned to complete autonomy. Positively put, we come out from God; we are sustained by God; and our proper destiny is to be with God."1

For further reflection:

* When and why have you felt most abandoned by God? What did it feel like?

* With what parts of Herbert's poem do you especially resonate?

* Why do you think that atheism has such little appeal to most people?

* Why are so many religious books on the bestseller lists?

* 1 John 4:16: "We know and rely on the love God has for us."

* See D.A. Carson, How Long, Oh Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil.

[1] "Praying the Psalms", Theology Today, 1989.