Mary and Martha: No Small Struggle

Week of Monday July 19, 2004

Lectionary Readings

Amos 8:1-12

Psalm 52; 15

Colossians 1:15-28

Luke 10:38-42

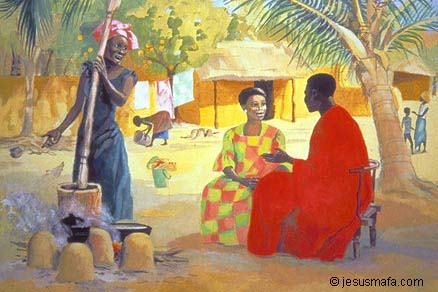

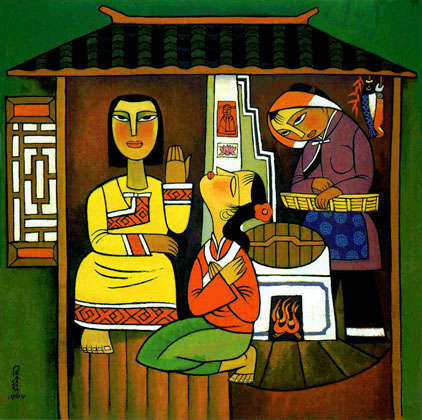

No one gives more attention to the prominent role that women played in the life of Jesus than Luke. The Gospel reading for this week (Luke 10:38-42) tells the story of the two sisters Mary and Martha. Immediately before this story Luke places the parable of the Good Samaritan to explain the second greatest commandment (to love our neighbor); the story of Mary and Martha illuminates the first and greatest commandment (to love God).

Now as they went on their way, he entered a certain village, where a woman named Martha welcomed him into her home. She had a sister named Mary, who sat at the Lord's feet and listened to what he was saying. But Martha was distracted by her many tasks; so she came to him and asked, "Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me to do all the work by myself? Tell her then to help me." But the Lord answered her, "Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her.

This remarkable incident records one of the very few (the only?) times that Jesus openly rebuked a person for the devotion and service they offered to him.

In the history of Christian spirituality this story is often taken as the paradigm par excellence to elevate the so-called “contemplative” life as superior to the “active” life. But read carefully, that is not what it is about. Rather, we could say that Luke contrasts Martha’s “distracted” exterior life with Mary’s “centered” interior life.

Martha worked frantically to offer the itinerant Jesus the best of hospitality and care, while her sister Mary did not lift a finger but instead lazed around the house.  Luke records that Martha was anxious, worried, harried, and irritated, so much so that she asked Jesus to rebuke Mary for leaving her to do all the work. How ironic that Martha’s feverish acts of devotion precipitated aggravation and annoyance, disquiet and disturbance. And so Jesus rebuked her and praised Mary’s passive, centered affection whereby she sat at his feet and listened to his teaching.

Luke records that Martha was anxious, worried, harried, and irritated, so much so that she asked Jesus to rebuke Mary for leaving her to do all the work. How ironic that Martha’s feverish acts of devotion precipitated aggravation and annoyance, disquiet and disturbance. And so Jesus rebuked her and praised Mary’s passive, centered affection whereby she sat at his feet and listened to his teaching.

Around the fourth century some Christians began to leave the frenzy of urban centers for the quiet of the desert. There, in monastic communities and as solitary hermits, they renounced the world, shed their possessions, and engaged in ascetic practices that today evoke only incredulity, satire, and scorn. But when you read their literature you learn that theirs was no superficial quest. The real spiritual warfare, they assure us, took place in the interior of the heart and not in the exterior renunciation of material things. The outer geography of the desert to which they had fled was one thing; the inner geography of the heart was another. Fighting hunger due to fasting, or devoting one’s sexuality to celibacy, were simple matters compared to battling inner rage, unconscious drives, unsavory dreams, depression, regret, envy, superficiality, lust and the like.

St. Hesychios (8th-9th century?) draws this contrast: “He who has renounced such things as marriage, possessions and other worldly pursuits is outwardly a monk, but may not yet be a monk inwardly. Only he who has renounced the impassioned thoughts of his inner self, which is the intellect, is a true monk. It is easy to be a monk in one’s outer self if one wants to be; but no small struggle is required to be a monk in one’s inner self.” Nikitas Stithatos (11th century) even argued that “the desert is in fact superfluous.” Far from concentrating on the exterior practices of asceticism, these saints sought an interior transformation of the heart.1

I have taken spiritual retreats at desert monasteries on three occasions. To get to Monastery of Christ in the Desert, you fly to Albuquerque, rent a car, and then drive for three hours. About 75 miles north of Santa Fe, just past Abiqui, you turn left off of highway 84 onto a single lane, limited access, dirt road and drive for thirteen bumpy miles until you dead end into a modest complex of buildings. There, about thirty Benedictine monks and nuns devote themselves to community, work, Scripture and prayer. I watched my connection to civilization fade on the face of my cell phone: “ATT...Extended Service...Roaming...No Service.”

True, the desert is quiet and peaceful, a place of silence and solitude, and gorgeous in its own, severe way. But the desert is also cold and windy at 6,500 feet, barren of most vegetation, lonely for an extrovert like me, and isolated from what most people consider “real” life. The bells to awaken us for Vigils at 4:00am also provoked the eerie howling of hyenas that echoed off the canyon walls. Electricity and water-pumping were solar powered. Guest rooms had no electricity. It took very little time to realize, though, that my real challenge was not to adjust to the barren desert, but to address the cacophony of voices in my head and heart that the contrast of the desert solitude only amplified.

The longest journey, wrote Dag Hammarskjold, is the journey inward. Hesychios is surely right; it is “no small struggle” to move from the experience of Martha, distracted, harried, and anxious, to some sense of Marian, quiet, centered interiority. Even if we can move beyond a life focused on the exteriors, we face many obstacles. We compare  our insides with other people’s outsides.2 Fear and discouragement hound us. And, as St. Makarios (fifth century) observed, no matter how much progress we make, our task this side of heaven will never be finished: “I am convinced that not even the apostles, although filled with the Holy Spirit, were therefore completely free from anxiety...Contrary to the stupid view expressed by some, the advent of grace does not mean the immediate deliverance from anxiety.”

our insides with other people’s outsides.2 Fear and discouragement hound us. And, as St. Makarios (fifth century) observed, no matter how much progress we make, our task this side of heaven will never be finished: “I am convinced that not even the apostles, although filled with the Holy Spirit, were therefore completely free from anxiety...Contrary to the stupid view expressed by some, the advent of grace does not mean the immediate deliverance from anxiety.”

Interiority is not narcissistic introspection or self-absorption. It is not generating some feeling of spirituality or trying to feel good about yourself, nor is it some special technique or obligation. A centered self is not some esoteric, spiritual superiority, or sanctimonious withdrawal from society or everyday responsibilities.3 When Jesus rebuked Martha, he told her that “there is need of only one thing.” He did not mean, “no need for a fancy meal, one dish will do.” In telling her that “Mary has chosen the better part,” He encourages us to let go of the false, exterior impersonations that we construct, and to offer our true, unadorned selves to Him.

1 The Philokalia, 1:174-175; 4:97.

2 Anne Lamott, Bird By Bird (New York: Random), p. 126.

3 Thomas Merton, The Inner Experience (San Francisco: Harper, 2003), p. 3.