For Sunday October 11, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Job 23:1-9, 16-17

Mark 10:17-31

Psalms 22:1-15

Hebrews 4:12-16

A righteous man on an ash heap. A rich man and a camel. A forsaken poet. A bone-piercing priest. Is it me, or is this week's lectionary a hodge-podge? What does Job's anguish have to do with the eye of a needle? Why place King David's famous lament ("My God, my God, why have you forsaken me") alongside the "living and active Word" of Hebrews 4? What do these readings have in common?

What I notice is this: each of the four texts is embattled. Each confronts a belief we take for granted, a received wisdom we hold dear, and turns it on its head. Each wrestles with false gods — the gods of convention, the gods of convenience, the gods of common sense — and breaks through to another God instead. A stranger, less palatable God. The God who is.

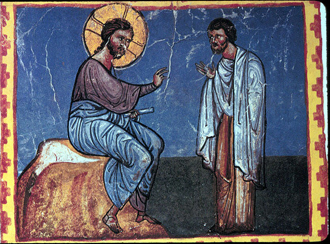

In the first reading, we find Job exactly where last week's lectionary left him. Still on his ash heap, still miserable, still surrounded by his clueless friends. One of those friends, Eliphaz, has just finished giving Job a lecture, and now it's Job's turn to respond. He does so in thundering indignation, each word testifying to the theological war raging within him. Who is God? Where is God? What can human beings reasonably expect from a life of faith?

|

|

God Speaks to Job. Megisti Lavra Monastery,Codex B. 100, 12th century.

|

Job's answers to these questions are shot through with ambivalence. God is nowhere: "If I go forward, he is not there; or backward, I cannot perceive him." And yet God is oppressively everywhere: "His hand is heavy despite my groaning… I am terrified at his presence." Job wants nothing more than to confront God face to face: "Oh, that I knew where I might find him, that I might come even to his dwelling!" And yet he's desperate to leave God's sight: "If only I could vanish in darkness, and thick darkness would cover my face!"

Job has full faith in his spiritual credentials: "I have not departed from the commandment of his lips." And yet he knows his credentials will not protect him: "But [God] stands alone and who can dissuade him? What he desires, he does."

Job is not a tame man seeking a tame God. He's a God-haunted man pursuing the passion of his life, only to crash again and again and again into mystery. His is religion at its wildest — a journey towards the Presence that is Absence, the Safety that is Terror, the Knowing that is always, in this life, an Unknowing.

If we read Job's story looking for coherence, we won't find it; it's a story at war with itself. In his book, How to Read the Bible, scholar James L. Kugel describes the Book of Job as a nuanced and unresolved dialogue between the Israelite wisdom tradition, and the realities of faith in a messy world. The wisdom tradition holds that God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked. In wisdom's worldview, prosperity is a sign of divine blessing, and deprivation signifies the withdrawal of that blessing. To suffer, in other words, is to experience God's displeasure.

It's this received "wisdom" Job must wrestle with when his life falls apart. It's the wisdom his friends attempt (and fail) to reconcile with lived reality. Interestingly, it's piety that keeps Job's friends from encountering God in this story. Strapped to the theology they know best, they find themselves sidelined when God finally shows up. And it's Job's "blasphemy" — his refusal to swallow any theology that doesn't jibe with the truth of his own life — that earns him an audience with God.

Let's fast-forward a few centuries. In this week's Gospel reading, a rich young man kneels at Jesus's feet. "Good Teacher," he says fervently, "What must I do to inherit eternal life?"

It's a pastor's dream question, isn't it? So much hunger, so much readiness — a soul ripe for the plucking? How easy it would have been for Jesus to secure a new and potentially useful convert. How effortlessly he could have said the warm and welcoming thing: "What? You've already followed the commandments for years? Excellent! And you're already calling me "good"? Then you must know who I am, because only God is good! Wow! I'm impressed! You're in!"

Or else Jesus could have worked by increments, coaching his new convert into the values of God's kingdom: "How about you write a small check to charity this year? Nothing scary, nothing that will break the bank. Just a token?"

|

|

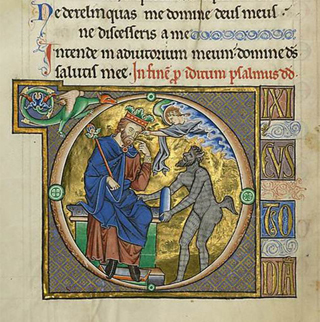

Jesus and the Rich Young Ruler. 11th Century.

|

But no. Jesus seems to have little interest in his followers' ease or comfort; those are my obsessions, not God's. He takes another route altogether. May I ask the question baldly? What kind of God sends a pious and searching soul away? "Jesus, looking at him, loved him," the text says. Jesus loved him — and so he said the truthful thing, the hard, unpalatable thing he knew would cause the young man's fervor to dissipate on the spot. "Sell what you own. Give to the poor. Follow me."

The text says the man "was shocked and went away grieving." No kidding. I imagine he was shocked because he considered his wealth an asset — a symbol not only of his worldly accomplishments, but also of God's favor. How terrible to be told that his best credential, his trump card — was a liability and a burden. How grievous to realize that God's kingdom was not automatically for him — that he might not like it, or agree with its priorities, or find common cause with its inhabitants. How shocking to encounter a God who is so scandalously honest — a God who freely hands us reasons to walk away.

Our Psalm reading this week, a pure lament, also gives us reasons to pause in our pursuit of the divine. "Oh my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest." "I am poured out like water… you lay me in the dust of death."

At the center of this lament is the poet's struggle to reconcile conflicting notions of who God is. In David's particular case, the battle is between the famed God of family lore, and the absent God who eludes him in real life. "In you our ancestors trusted," he cries out in confusion. "They trusted, and you delivered them."

So what about me? "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" For those of us who grew up in the Church, steeped in the spiritual stories of other believers, this is a cry we can relate to. Like David, we trace our faith histories back a long way: "On you I was cast from my birth, and since my mother bore me you have been my God."

Of course, it's entirely appropriate to draw strength and inspiration from our spiritual histories. And yet somewhere along the way, we might find that the God who was — the God whose stories we know; the God we've learned to trust by way of tradition, ancestral history, or community lore; the God whose faithfulness we assume will look identical from year to year, generation to generation — doesn't jibe with the life we find ourselves in. In such moments, we discover that it's one thing to know God in abstraction, and another to know him personally. David's cry is a plea for relevance — I know the God of my ancestors. But who is God right here? Right now? For me?

|

|

King David and God's Absence. 13th century illuminated manuscript.

|

Which brings us to Hebrews 4:12-16, a passage that epitomizes the tensions running through this week's lectionary. The writer of Hebrews describes the Word of God as active, sharp, and piercing — a two-edged sword that divides soul from spirit, joint from marrow. He is a naked-making Word — a Word who sees all, exposes all, and judges all.

And yet this Word is also a merciful and gracious high priest — the Son of God who knows our weaknesses and vulnerabilities, the One whose throne we can approach with honesty and full confidence.

How can he be both? Piercing and gracious? Judging and sympathetic? How can the Word that cuts be the Word that heals? With God, Jesus tells the rich young man, the impossible is possible.

Read together, these four lectionary texts defamiliarize God. They challenge us to encounter him freshly, apart from tradition, memory, theology, and abstraction. If we're willing to engage with the tensions in these readings, they can offer surprising clues about who God is and what he cherishes. He is a God who dismisses the pious to answer a loudmouth on an ash heap. He is a God who loves us enough to let us walk away. He is a God who will not allow us to rest on our histories. He is a God whose grace cuts deeper than a sword.

May we dare to wrestle past the gods we have known — the gods who keep us safe but cannot save us. May we approach with boldness the untamed God who will.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Index of Armenian Art; and (3) The Center for Biblical and Theological Education, Seattle Pacific University.