For Sunday September 11, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 4:11–12, 22–28 or Exodus 32:7–14

Psalm 14 or Psalm 51:1–10

1 Timothy 1:12–17

Luke 15:1–10

After hiking for a month in rural Italy on the Way of St. Francis this July, my wife and I walked around Rome for a week. We were typical tourists, which meant that one of our stops was the Christian catacombs.

There are nearly sixty catacombs, five of which are open to the public. We went to the oldest and one of the largest and best preserved catacombs, Domatilla, with nine miles of underground caves that held 150,000 bodies.

The catacombs contain a treasure trove of the earliest known Christian art. Art and architecture flourished in classical Greece and Rome, of course, but Christians were slow to express their ideas about the Word in images. Jeffrey Spier writes, "no churches, decorated tombs, nor indeed Christian works of art of any kind datable before the third century are known."

Around the year 200, "purely Christian images began to appear." The catacombs in and around Rome, along with the discovery of a house church at Dura Europos in Syria dated to 240 AD, show how the earliest Christian art was not merely decorative but intentionally devotional; its purpose was not "objective beauty" but an "expression of faith."

|

|

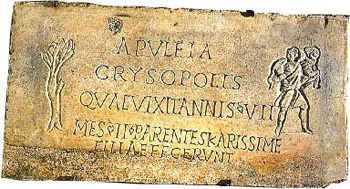

An inscription dedicated by parents of a deceased 7 year old girl, Apuleia Crysopolis, with Good Shepherd, Catacomb of St. Callisto, Rome.

|

This early Christian art appears on seal rings, tombs, clay lamps, engraved gems, and in one instance a marble statuette. A hundred years after that, Christian art adorns belt buckles and Bible covers, plates and coins, intricate mosaics and ornate crosses. Eventually, Christian art under Constantine changed radically, as images and even architecture became "imperialized."

Most early Christian art drew upon well-known Bible texts like Noah, Daniel in the lion's den, Moses, Jonah, Adam and Eve, and Abraham. The gospel for this week is a case in point — Jesus the Good Shepherd is portrayed in all sorts of artistic mediums (cf. the five images with this essay). It's far and away one of the most common artistic motifs.

The life of Jesus reveals the heart of God. He does this with crystalline clarity in Luke 15, which says that "this man welcomes sinners and eats with them." To emphasize this Divine Welcome, God's unconditional acceptance, Jesus tells three parables that repeat the same point — the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son.

|

|

Fresco of Jesus the Good Shepherd in the Coemeterium Majus catacomb, Rome, 3rd century.

|

When Jesus finds the lost sheep, writes Luke, "he joyfully puts it on his shoulders." This detail is exactly what we see in the wall painting in the Catacomb of Priscilla.

People felt safe with Jesus. He exuded compassion.

Jesus welcomed the people we ignore and despise. The sexually suspicious. The religiously impure. Ethnic outsiders. Rich tax scammers and lazy poor people. Soldiers of the Roman oppressors. The chronically sick and the mentally deranged. Women with multiple marriages, widows and children. His closest disciples who betrayed him.

The people who didn't feel safe with Jesus were the religious experts who appointed themselves as gatekeepers of God's love. They had good reasons to feel unsafe. In Matthew 23 Jesus denounced them with "seven woes" as hypocrites, snakes, and blind guides.

When Jesus welcomed the unwelcomed, when he accepted the unacceptable without any preconditions, he angered the religious experts. Luke says that they "muttered." In the parable of the prodigal son, the older son got angry at his father's indiscriminate compassion for his younger brother.

|

|

Sarcophagus of the Good Shepherd, Catacomb of Praetextatus, Rome, 390s.

|

Whether then or now, there's a bitter irony in how the simple act of accepting another person angers some people. But whereas the gatekeepers get angry, Jesus says three times that there's "joy in heaven" when the lost sheep is rescued, when a misplaced coin is found, and the prodigal son comes home.

In this week's epistle, Paul uses himself as an example of God's "unlimited patience." God's welcome, says Paul, is "a trustworthy saying that deserves full acceptance."

Throughout the New Testament, Paul describes himself as a former religious zealot who tried to exterminate the early Christian movement.

In Acts, he supported the stoning of Stephen, the first Christian martyr. "Breathing threats of murder," Paul collaborated with authorities to track down believers from house to house, drag them back to Jerusalem, and imprison them. He worked fervently to "destroy the church."

|

|

Third century marble statue of the Good Shepherd, from the Catacomb of Domitilla, now in Museo Pio Cristino, Vatican.

|

To the Corinthians he admitted that he didn't deserve to be called an apostle, and was instead the "least of the apostles" because of his violent past.

To the Galatians Paul wrote, "For you have heard of my previous way of life in Judaism, how intensely I persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it. I was advancing in Judaism beyond many Jews of my own age and was extremely zealous for the traditions of my fathers."

To the Philippians he bragged, "as to zeal, a persecutor of the church."

And in this week's epistle to Timothy, as an old man Paul was still haunted by his past. He describes himself as "formerly a blasphemer and a persecutor and a violent aggressor."

But God welcomed Paul. And his conversion moved him from violent aggression to indiscriminate love.

We don't need to do anything to receive God's welcome, because there's nothing to do. God welcomes us just like we are and right where we are. Martin Luther described faith as the beggar's empty hand that accepts a gift.

And so the beautiful words in the powerful poem by Edwina Gateley: "Let your God love you. / Say nothing. / Ask nothing. / Let your God look upon you. / That is all."

The only thing to do is to accept that we are accepted. In the words of Paul Tillich, "You are accepted. You are accepted by that which is greater than you, and the name of which you don’t know… Simply accept the fact that you are accepted. If that happens, we experience grace."

|

|

Fresco of the Good Shepherd, Catacomb of Priscilla.

|

"Grace tells us that we are accepted just as we are," writes Donald McCullough. "We may not be the kind of people we want to be, we may be a long way from our goals, we may have more failures than achievement … but we are nonetheless accepted by God, held in his hands. Such is his promise to us in Jesus Christ, a promise we can trust."

Safe with the Good Shepherd — a trustworthy saying that deserves full acceptance.

NOTE: See Jeffrey Spier, editor, Picturing the Bible; The Earliest Christian Art (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Kimbell Art Museum, 2007), 309pp.

Image credits: (1) JesusWalk.com; (2) Yale Divinity Digital Image & Text Library; (3) JesusWalk.com.; (4) JesusWalk.com; and (5) Wikipedia.org.