For Sunday April 23, 2017

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 2:14a, 22–32

Psalm 16

1 Peter 1:3–9

John 20:19–31

It's the very first Sunday after Easter, but the epistle for this week catapults us a long way away from that tumultuous holy week in Jerusalem — in terms of time, place, and people. We're not sure who wrote 1 Peter, or exactly when, but a careful reading of the letter reveals important clues about that community's life of faith.

The epistle was written about sixty years after the resurrection events. The recipients of the letter were likely second generation Christians. The very first verse of the letter indicates that 1 Peter is a circular letter written to Gentile believers who lived in five Roman provinces a thousand miles east of Rome, in what is now north-central Turkey.

The author writes to them from Rome, but he doesn't use the word "Rome." Rather, he uses the politically provocative code word "Babylon" (5:13). It's hard to think of a more derogatory epithet than that ancient empire which conquered and subjugated God's people way back in 586 BCE. John similarly disparages Rome as "the Great Babylon, the mother of whores and of the abominations of the earth who is drunk with the blood of the saints" (Revelation 17:5–6).

Like the author of the letter, the recipients had "broken with the social fabric of their community" (OSB). Or as the NT scholar Joel Green puts it, "First Peter is addressed to folks who do not belong, who eke out their lives on the periphery of acceptable society, whose deepest loyalties and inclinations do not line up very well with what matters most in the world in which they live."

Three times the letter characterizes the believers as "strangers and aliens" to Rome's paganism. They are a "scattered" people, a diaspora of believers who live a life of exile. They belonged to their own peculiar "people and nation" (1:9).

These believers didn't conform to the social conventions of the day. 1 Peter describes them as "maligned" and "reviled." Indeed, their detractors "think it strange that you do not plunge with them into the same flood of dissipation, and they heap abuse on you." Even "the name" Christian was offensive to their detractors (4:14, 16).

|

|

The Whore of Babylon rides the seven-headed Beast, 18th-century Russian engraving.

|

For some years after Jesus, Christians remained invisible to the greater Roman empire. But across the decades, they earned a reputation as an anti-social community that lived on the fringes of society. They were considered fanatical, seditious, obstinate, and defiant. The historian Tacitus, who died in 117, called them "haters of mankind."

In his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776), Edward Gibbon argued that the success of the early Christians was based upon their "intolerant zeal" of Roman ways. That is, the new faith was utterly incompatible with and "obstinately different" from the old ways of the ancient empire.

There are some early texts that support this oppositional paradigm, like the one by a Roman lawyer and Christian named Minucius Felix of the early third century. He wrote a dialogue between a Christian named Octavius and a pagan critic called Caecilius. Whether the dialogue is actual history or just a literary device isn't clear. What's clear, though, is that in this telling, Roman believers lived on the cultural fringes.

Since the Christian sect was new and novel, and couldn't claim an ancient pedigree, it was automatically suspect. Many of its adherents were also "unlettered and unlearned" (Clarke), or in Caecilius's snobbery, "utter boors and yokels, ungraced by any manners or culture."

In style and content their Scriptures were crude. They believed absurd doctrines like the resurrection of the body and providence. Rumors about their cannibalism, incest, and infanticide were well known.

And so, Caecilius complains and condescends at length:

"They despise our temples as being no more than sepulchers, they spit after our gods, they sneer at our rites, and, fantastic though it is, our priests they pity—pitiable themselves; they scorn the purple robes of public office, though they go about in rags themselves."

"You do not go to our shows, you take no part in our processions, you are not present at our public banquets, you shrink in horror from our sacred games, from food ritually dedicated by our priests, from drink hallowed by libation poured upon our altars. Such is your dread of the very gods you deny. You do not bind your head with flowers, you do not honor your body with perfumes; ointments you reserve for funerals, but even to your tombs you deny garlands; you anemic, neurotic creatures, you indeed deserve to be pitied — but by our gods. The result is, you pitiable fools, that you have no enjoyment of life while you wait for the new life which you will never have… If you have not been privileged to understand the concerns of a citizen, you most surely have been denied discussion of the affairs of heaven."

Then comes the clincher. The Christians, griped Caecilius, "do not understand their civic duty." They were outliers.

|

|

Thrown to the lions.

|

Rome responded to Christian sedition and separatism with state persecution, some times sporadic and at other times by official policy. The first few sentences of 1 Peter describe how the believers "suffered grief in all kinds of trials." They shouldn't be surprised by these "fiery trials," he says, as if their persecutions were strange or unexpected. Indeed, he encouraged them, "you know that your brothers throughout the world are undergoing the same kind of suffering" (5:9).

It's no wonder that these believers who suffered social marginalization and political persecution felt like "the end of all things is near." For some of them it was. The writer thus recommends a strategy of survival. Slaves should submit to their harsh masters. Wives should submit to their unbelieving husbands, and young men should submit to older men (3:1, 5:5). There was enough trouble in the world without looking for more. To make the best of a bad situation, sometimes compromise is necessary and wise.

An exemplary life was the best response to charges of civic indifference and political sedition. In his treatise Against Celsus (VIII.73), Origen (185–254 AD) described how Christians best served society in their own peculiar way:

And as we—by our prayers—

vanquish all the demons that stir up war,

and lead to the violation of oaths,

and disturb the peace,

we in this service

are much more helpful to the kings

than those who go into the field

to fight for them.And we do take our part in public affairs,

when along with righteous prayers,

we practice self-denying disciplines and meditations,

which teach us to despise pleasures,

and not to be lead astray by them.

And none fight better for the king

[and his role of preserving justice]

than we do.

We do not indeed fight under him,

although he demands it;

but we fight on his behalf,

forming a special army of piety

by offering our prayers to God.

In some mysterious way, enduring unjust suffering participates in the sufferings of Christ himself (4:13). And at the end of history, there will be a Great Reversal, when every angel, authority, power and human institution will be "in submission to him" (3:22).

Two centuries after 1 Peter was written, there came a remarkable historical paradox: the greatest persecutor of the church (the Roman state) became its biggest supporter (Constantine) and the center of its ecclesiastical power (the Roman papacy).

|

|

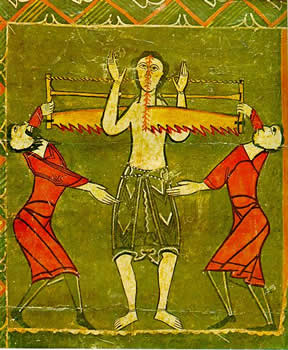

Hebrews 11:37: "They were sawed in two."

|

For further reflection

Epistle to Diognetus (c. 130):

"For Christians are no different from other people in terms of their country, language or customs. Nowhere do they inhabit cities of their own, use a strange dialect, or live life out of the ordinary. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They live in their respective countries, but only as resident aliens; they participate in all things as citizens, and they endure all things as foreigners. Every foreign territory is a homeland for them, and every homeland a foreign territory. They marry like everyone else and have children, but they do not expose them once they are born. They share their meals but not their sexual partners. They are found in the flesh but do not live according to the flesh. They live on earth but participate in the life of heaven. They are obedient to the laws that have been made, and by their own lives they supersede the laws. They love everyone and are persecuted by all. They are not understood and they are condemned. They are put to death and made alive. They are impoverished and make many rich. They lack all things and abound in everything. They are dishonored and are exalted in their dishonors."

Image credits: (1) Toast.net; (2) Hornbill Unleashed blog; and (3) Michael Gaddis, Maxwell School of Syracuse University.