For Sunday October 23, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Joel 2:23–32 or Jeremiah 14:7–10, 19–22

Psalm 65 or Psalm 84:1–7

2 Timothy 4:6–8, 16–18

Luke 18:9–14

In the fall of 2003, I spent two weeks in Oxford revising my book Eastern Orthodox Christianity (1994, 2003) for a second edition. On Sunday, I walked down to Saint Aldate's Church on Pembroke Street in the center of town. No one knows who Saint Aldate was, but the church's first rector, Reginald, started serving the church in 1226.

As I walked into St. Aldate's, the usher handed me a bulletin and enthusiastically greeted me, “We welcome all sinners!" He had no way of knowing it, but those were the words that I needed to hear right then and there.

These words summarize the mission of Jesus: ”I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” They echo the accusation of his enemies: “this man welcomes sinners.” The gospels tell how "many sinful people" followed Jesus. These people felt safe with Jesus, somehow sheltered rather than judged.

In his book The Parables of Jesus, Joachim Jeremias shows how there's a whole group of parables that emphasizes God's love for sinners. Remarkably, these parables share a unique characteristic — they're all addressed directly to the enemies of Jesus.

These parables don't merely announce the good news, they also vindicate it. “They are a controversial weapon against the critics and foes of the Gospel," says Jeremias, "who are indignant that Jesus should declare that God cares for sinners."

Some of the parables describe what sinners are like. True prodigals have no pretensions. A second group invites the self-righteous to consider what they are like. In the parable of the Two Sons, they're like a child who didn't do what he promised. Third, there are the parables that describe what God is like. In the Prodigal Son, God is like a welcoming and waiting father.

|

|

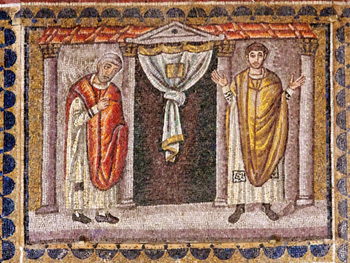

The Pharisee and the Tax Collector.

|

The parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector in Luke 18 contrasts two characters. They're polar opposites, and set in bold relief two ways of being religious. One way is death-dealing, the other way is life-giving.

The Pharisee was religiously righteous, the tax man extorted revenue for the Roman oppressors. The religious expert was smug and confident, the outsider was anxious and insecure. The saint paraded to the temple, the sinner "stood at a distance" — as if his physical distance from the sacred building expressed his spiritual alienation. The righteous man stood up, the sinful man looked down. In an act of shocking narcissism, the Pharisee prayed loudly "about himself"; the tax collector could barely pray at all. The Pharisee puffed out his chest in pride; the publican beat his breast in sorrow.

The parable punch line announces a reversal. The respectable, reputable believer, so competent and accomplished, the one who had done everything right, was rejected, whereas the secular sinner — disreputable, inadequate, and incompetent — "went home justified before God."

It's hard to imagine a more earnestly religious person than the Pharisee. He prayed often, he fasted regularly, and he gave generously to the poor. His spiritual regimen was stringent. But he made two tragic mistakes in his religious life, one about himself, and one about other people, the combination of which is toxic to authentic spirituality.

First, the Pharisee "looked down on everybody else." Contempt for others lurks in the human heart, bubbling up easily and frequently. We imagine that in denigrating others we validate ourselves, or that at least we will compare favorably.

"We all stumble in many ways," writes James. What we need when we flounder isn't moral condescension, but human compassion, not humiliation but empathy, not shame but hope.

|

|

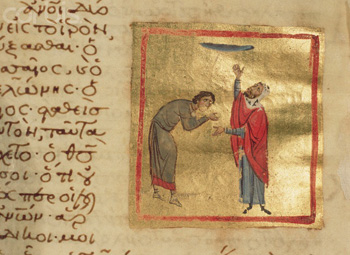

The Pharisee and the Tax Collector.

|

I've always loved the tender wisdom of St. Maximos the Confessor (seventh century): "The person who has come to know the weakness of human nature has gained experience of divine power. Such a person never belittles anyone… He knows that God is like a good and loving physician who heals with individual treatment each of those who are trying to make progress."

The flip side of condescension toward others is justification of yourself. This was the Pharisee's second mistake. The Pharisee thanked God that he was "not like other people" — a thief, an evildoer, or an adulterer. His religious narcissism was a form of spiritual self-justification.

We'll invoke almost anything to justify ourselves — intelligence (GPA and SAT), alma mater ("This is where I went to school thirty years ago"), money ("I'm frugal toward myself and generous to others"), family ("Great kids!"), sports ("I'm in shape, you're a slob"), politics ("My vote is enlightened, yours is ideological"), and work ("I work at X; what do you do?"). A common form of self-justification invokes your zip code ("Where do you live?"), a transparent insinuation that net worth equals self worth.

To a greater or lesser degree, I've tried all of these self-justifications; they don't work. Society is relentless in demanding proofs and justifications from us, and it's easy to take the bait, especially if you're an accomplished person with lots of ammunition who — in all modesty, right? — can rise to the challenge.

But self-justification doesn't work, and it isn't necessary, for in the words of the famous hymn, God accepts me "just as I am." Full stop.

We should listen to the wisdom of the fourth-century desert saint John the Dwarf: "We have put aside the easy burden, which is self-accusation, and weighed ourselves down with the heavy one, self-justification."

|

|

The Pharisee and the Tax Collector (from the Harvard Art Museum).

|

To live without self-justifications makes me feel vulnerable. But when you think about it, living without self-justifications is extraordinarily liberating. As soon as you accept that you're accepted by a good God, you never, for any reason, need to prove yourself.

To get to that place, Jesus says that we need only seven words — those mumbled by the tax collector as he stood at a distance and stared at the ground: "God, have mercy on me, a sinner." The moment we breathe those words and cast our unadorned selves upon God, we experience his love without conditions or limits.

This, of course, is "The Jesus Prayer." Rightly understood, and spoken from the heart, that's the most important prayer anyone can utter, and in a sense the only prayer you'll ever need. Why? Because it proceeds from a clear-eyed appraisal of our human condition and, more importantly, from confidence in the character of a God who welcomes sinners — and even self-righteous saints.

For further reflection

* The early monastics on judging others:

"The monk, says Moses, must never judge his neighbor at all in any way whatever."

"They said of Abba Macarius that just as God protects the world, so Abba Macarius would cover the faults he saw, as though he did not see them, and those he heard, as though he did not hear them."

* Consider Mrs. Turpin from the short story "Revelation" by Flannery O'Connor. She was a good, decent, upright, and proud woman who did everything right, except that she was a self-righteous racist. She was a person, writes O'Connor, who, when she entered heaven, needed "even her virtues burned away."

Image credits: (1) St. George Byzantine Catholic Church; (2) Domini Canes; and (3) Harvard Library.