Ancient Words for Modern Life: The Ten Commandments

by Dan Clendenin

For Sunday October 5, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 20:1–4, 7–9, 12–20 or Isaiah 5:1–7

salm 19 or Psalm 80:7–15

Philippians 3:4b–14

Matthew 21:33–46

Last month I read a book by Michael Coogan called The Ten Commandments (Yale, 2014). Rabbinic tradition says there are 613 commandments in the Old Testament, but as Coogan observes, for Jews and Christians the Ten Commandments have always enjoyed a privileged status.

There are three different versions of the Ten Commandments — Exodus 20, Deuteronomy 5, and Exodus 34. The first four commandments describe God's relationship with his people — the prohibitions against polytheism and images, the sanctity of God's name, and the sabbath rest. The last six commands, says Coogan, are general, not unusual in ancient law codes, and could apply to many diverse societies — parents, murder, adultery, kidnapping, perjury, and property.

Despite their privileged status, there's always been significant ambiguity about the role of the Decalogue in our modern lives. It's easy to think of many examples.

|

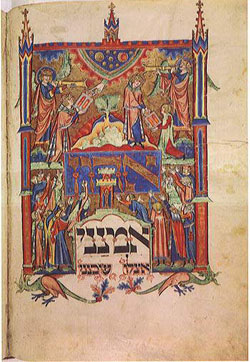

Moses receives the 10 commandments,

Jewish prayer book, Germany, c. 1290. |

By one count there are 4,000 public displays of the Ten Commandments, including the Supreme Court itself and the Library of Congress. Sometimes the Supreme Court has allowed the public display of the Ten Commandments, while other decisions have barred them.

Zeal for the commandments runs high, but so does ignorance. A 2004 Barna poll indicated that 79% of Americans oppose the idea of removing displays of the Ten Commandments from government buildings, even though another survey indicated that fewer than 10% of Americans can identify more than four of the commandments.

In the 10th commandment about coveting, Coogan observes that it's assumed that slaves and women are part of a man's property.

Neither Jews nor Christians have consistently observed the prohibition against images. The iconoclastic controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries debated the relationship between images and idolatry. Some Christian churches incorporate elaborate images, while other buildings have four whitewashed walls.

Luther and Calvin disagreed sharply about the role of the law in the life of a Christian. Their respective catechisms reflect this. But they could both be ambiguous.

Luther emphasized the freedom of a Christian from law, but his Larger Catechism also says that “whoever knows the Ten Commandments perfectly knows the whole of Scripture.”

For Calvin, the Ten Commandments played a central role in the life of the church and even in broader society. The Heidelberg Catechism (1563) contains a long exposition of all the Ten Commandments, but when it then asks whether a Christian might keep these commandments perfectly, the response is refreshing for its candor: "No, for even the holiest believer makes only a small beginning in obedience in this life."

The enemies of Jesus criticized him for breaking the law. He responded that he didn't come to abolish the least bit of the law but to fulfill it.

|

Moses, Salvador Dali, 1975. |

In Romans and Galatians, Paul insists that Christ is "the end of the law." This week's epistle to the Philippians emphasizes this point. But Paul also said that "we do not set aside the law."

Despite such ambiguities and complexities, the Ten Commandments are a moral compass that points us toward the true north of human health and wholeness. In neglecting them we lose our way. In this sense the Ten Commandments are promises that give life rather than prohibitions that repress.

The Ten Commandments aren't moral abstractions, says Chris Hedges. In his book Losing Moses On The Freeway; The 10 Commandments In America (2005), he writes, "There is nothing abstract about the commandments to those who know the sting of their violation or have neglected their call."

The commandments save us from false covenants and idols that promise so much and deliver so little. Hedges desacralizes the contemporary idols that we so readily worship — the state, the nation (especially in its glorification, legitimation, and sacralization of war and violence), race, religion, ethnicity, gender, sex, and economic class.

The commandments, says Hedges, frame the most important questions we can ask, like the mystery of good and evil, the meaning of living in community, the nature of integrity, the meaning of fidelity, or the necessity of honesty. In honoring the commandments, we embrace the sanctity of life, the power of love, and their function to bind us together in life-affirming community.

The third commandment in particular saves us from our besetting sin of presumption: "You shall not misuse the name of the Lord."

It's shocking to me how casually and confidently we speak about God. The third commandment evokes the tragic fate of Nadab and Abihu. When they were killed for offering "strange fire" before the Lord, God responded, "By those who come near me I will be treated as holy."

|

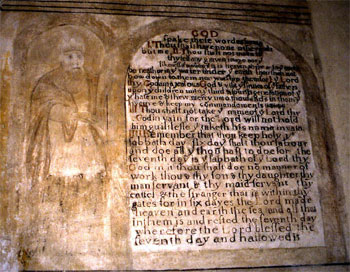

Moses and the 10 Commandments, 16th century church fresco. |

To bestow a name, to use a name, or to know a name, says Coogan, is an "expression of control." When Adam and Eve named the animals in Genesis, it expressed their "dominion" over them. When conquering nations subdue an enemy, they often change their names as a sign of subjugation (cf. the book of Daniel).

Despite the casual confidence with which we speak, control or dominion over the name of God is precisely what no person can have. Ever. The very thought is blasphemous. Coogan gives two examples.

When Jacob asks the divine messenger to tell him his name, the response is evasive, "Why do you ask my name?" Similarly, when Manoah asks the angel of the Lord, "What is your name?" the reply is similar: "Why do you ask my name? It is beyond understanding."

These two examples echo God's famously evasive response to Moses, who also asked about God's name: "I am who I am."

And so Jews honor the mysterious, the inexpressible, and the inviolable name of "God" (YHWH) by not even pronouncing it. Instead, they substitute the word "adonay" or "Lord." Or sometimes you might hear an observant Jew refer to God as Hashem — "The Name."

The third commandment about the name of God warns us not only about our casual presumptions. It reminds us of the limits of our language when we speak about the Wholly Other God. CS Lewis captures the practical implications of this in his Footnote to All Prayers.

He whom I bow to only knows to whom I bow

When I attempt the ineffable Name, murmuring Thou,

And dream of Pheidian fancies and embrace in heart

Symbols (I know) which cannot be the thing Thou art.

Thus always, taken at their word, all prayers blaspheme

Worshiping with frail images a folk-lore dream,

And all men in their praying, self-deceived, address

The coinage of their own unquiet thoughts, unless

Thou in magnetic mercy to Thyself divert

Our arrows, aimed unskillfully, beyond desert;

And all men are idolaters, crying unheard

To a deaf idol, if Thou take them at their word.

Take not, O Lord, our literal sense. Lord, in thy great

Unbroken speech our limping metaphor translate.

This isn't the last thing or only thing we could say about the inexpressible name of the infinite God. But maybe it should be the first.

These limitations can be a liberation. I no longer have to pretend that I understand God. The mystery of prayer becomes something to honor rather than to explain. I don't even need to be right, for in his "magnetic mercy" God will "our limping metaphor translate."

Having honored the third commandment as best we can, we're prepared for the shocking words of Jesus — that God is not only the Infinite Other. He's also my Intimate "Abba."

For further reflection:

* You shall have no other gods before Yahweh.

* You shall not make for yourself an idol.

* You shall not misuse the name of the Lord your God.

* Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy.

* Honor your father and mother.

* You shall not murder.

* You shall not commit adultery.

* You shall not steal.

* You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor.

* You shall not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor.

* Watch the classic film The Decalogue (1988) by Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski, a series of ten one-hour films about each of the commandments. Also available as a book by K. Kieslowski, Decalogue: The Ten Commandments (London: Faber and Faber, 1991).

* See also David W. Gill's book on the 10 Commandments, Doing Right; Practicing Ethical Principles (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2004).

Image credits: (1) Library of Congress; (2) PicassoMio; and (3) PaintedChurch.org.