Remembering Wars, Waging Peace

For Sunday July 6, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 24:34–67 or Psalm 45:10–17 or Song of Solomon 2:8 –13

Zechariah 9:9–12 or Psalm 145:8–14

Romans 7:15–25

Matthew 11:16–19, 25–30

By a coincidence of the calendar, this week we remember two violent revolutions that shook the world.

Here in the United States, Americans will celebrate "Independence Day" on the 4th of July.

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress of the thirteen American colonies approved a resolution to declare independence from Great Britain. Henceforth they would be a sovereign nation of thirteen "United States." Two days later, on July 4, the Congress approved the "Declaration of Independence" that explained their vote.

|

F-16s fly over Colorado on the 4th of July. |

This national celebration always feels awkward and ambiguous to me. This is partly for personal reasons. Both my wife and my daughter were born on the 4th of July, so I'm naturally more excited about their birthdays than the jet flyovers at baseball games. But there are also deeper reasons for my unease.

This week the entire world will also observe the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I. On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo. By the time the fighting ended with the armistice of November 11, 1918, more than 16 million people had been slaughtered. Another 20 million people were wounded.

Both of these celebrations will be occasions for parades, picnics, political speeches, and especially displays of patriotism. There's nothing wrong with all that. And perhaps our human propensity to greed and violence makes some wars "good" and even necessary. But God calls his people to look beyond superficial celebrations and jingoistic rhetoric.

The earliest followers of Jesus, and especially his detractors, used the political language of kingship to describe who he was, what he said, and what he did. Every king enjoys a reign, a rule, and a kingdom. Jesus was no exception. His very first words of public ministry proclaimed that in him "the kingdom of God is at hand." But his ideas about kingship radically subvert our normal political narratives.

After three years of preaching, teaching, and healing that focused on the poor, the imprisoned, the blind, and the oppressed, Jesus's family declared him insane. The religious establishment hated him, and the political authorities had had enough. And so Rome deployed all the brutal means at its disposal to crush an insurgent movement — rendition, interrogation, torture, mockery, humiliation, and then a sadistic execution designed as a "calculated social deterrent" (Borg) to any other trouble makers who might challenge imperial authority and disturb the Pax Romana.

In a sermon at Cornell University from 1969, William Stringfellow observed that we often say that Jesus was an innocent victim. No, says Stringfellow, Jesus was justly accused as a guilty criminal. He was "not a mere nonconformist, not just a protester, more than a militant, not only a dissident, not simply a dissenter, but a criminal." Even more, "the most dangerous and reprehensible sort of criminal." Why? Because "he threatened the nation in a revolutionary way."

This is exactly what Luke describes.

|

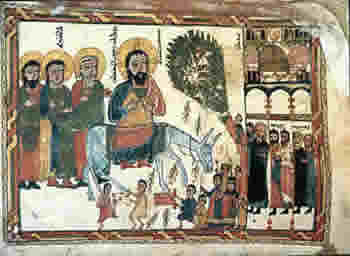

Jesus's Triumphal Entry, Medieval Syriac manuscript. |

Jesus was executed for three reasons, says Luke: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King." In John's gospel, the angry mob warned Pilate, "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar."

In short, "He's subverting our nation. He opposes Caesar. You can't befriend both Jesus and Caesar." They were right, more right than they knew or could have imagined.

Because the Roman state always made a show of military force during the Jewish Passover when pilgrims thronged to Jerusalem to celebrate their political liberation from Egypt centuries earlier, Borg and Crossan imagine not one but two political processions entering Jerusalem that "Good Friday" morning in the spring of AD 30.

In a bold parody of imperial politics, king Jesus descended the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem from the east in fulfillment of Zechariah's ancient prophecy: "Look, your king is coming to you, gentle and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey" (Matthew 21:5 = Zechariah 9:9). From the west, the Roman governor Pilate entered Jerusalem with all the pomp of state power.

Pilate's brigades showcased Rome's military might, power and glory. Jesus's triumphal entry, by stark contrast, was an anti-imperial and anti-triumphal "counter-procession" of peasants that proclaimed an alternate and subversive community of "the kingdom of God."

This wasn't a spontaneous event. It was a deeply ironic, highly symbolic, and deliberately provocative act. It was an enacted parable or street theater that dramatized Jesus's subversive mission and message. He didn't ride a young donkey because he was too tired to walk or because he wanted a good view of the crowds. The Oxford scholar George Caird characterized Jesus's triumphal entry as more of a "planned political demonstration" than the religious celebration that we sentimentalize today.

It doesn't stop there. Believers worship Jesus not only as king of the Jews, but also as "the king of kings" (1 Timothy 6:15, Revelation 19:16), the "king of the ages" (Revelation 19:3), and "ruler of the kings of the earth" (Revelation 1:5). When God raised Jesus from the dead, he "seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come."

In what ways does Jesus subvert our political status quo?

Johnny Cash, World War I, When The Man Comes Around. |

The fuller passage in Zechariah 9 points the way. God's kingdom is one of peace and not war: "I will take away the chariots from Ephraim and the war-horses from Jerusalem, and the battle-bow will be broken. He will proclaim peace to the nations." We should abhor war, not glorify it.

God's kingdom is also universal rather than nationalistic. No nation is exceptional before him, and no nation is excluded. "His rule will extend from sea to sea, and from the river [Euphrates] to the end of the earth." God's kingdom subverts every sort of national vanity.

Finally, as the attached Johnny Cash music video makes clear, Christians anticipate God's judgment. We hope for some kind of Divine Accountability for all the violence inflicted on so many people around the world. Nothing good will be lost. Nothing evil will endure. Human suffering will find divine solace.

For Christians who believe that God loves all peoples and nations without exception or favoritism, and who wish every nation peace rather than violence, the anniversaries of the American Revolution and World War I invite us to deeper reflections beyond patriotic rhetoric. Zechariah's peace poetry invites us to imitate his God, and to love all the world like he does.

For further reflection:

Scott Anderson, Lawrence in Arabia; War, Deceit, Imperial Folly, and the Making of the Middle East (New York: Doubleday, 2013), 577pp.

Andrew Bacevich, Breach of Trust; How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2013), 238pp.

David Finkel, Thank You For Your Service (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2013), 256pp.

Mark Holborn and Hilary Roberts, The Great War; A Photographic Narrative (New York: Knopf, 2013), 504pp.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

By some accounts the most famous war poem of WW I. DULCE ET DECORUM EST — the first words of a Latin saying (taken from an ode by Horace). The full saying ends the poem: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori — it is sweet and right to die for your country. On November 4, 1918 Owen was shot and killed near the village of Ors. Armistice bells rang on November 11, celebrating the end of WW I.

Image credits: (1) 140th Wing, Air National Guard; (2) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University; and (3) YouTube.com.