Coming Back for More:

Why Go to Church?

For Sunday January 19, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 49:1–7

Psalm 40:1–11

1 Corinthians 1:1–9

John 1:29–42

Hildred Esterly was fourteen years old when her father became the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Columbiana, Ohio. That was in 1917. My grandmother stayed in that church for seventy-nine years. She was buried there in 1996 at the age of ninety-three. That's a long life in one church.

My father had a different experience. When I was in high school, he quit church. He never went back, and he never said why. I don't know this to be true, but I like to think that he lost his faith in the church as an institution but not his faith in God or the gospel.

There are lots of reasons to quit church. Good ones. Tops on most lists are hypocrisy, violence, and intolerance. In the name of God's love we've slaughtered Muslims (the Crusades), Jews (the Holocaust) and Native Americans. We've humiliated and exploited slaves, women and gays. Clerical pedophilia has devastated thousands of families. And whether Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant, fellow Christians have persecuted each other with sadistic cruelty.

Others find church to be irrelevant, mediocre, boring or perfunctory. Here's Annie Dillard in her essay An Expedition to the Pole: "Week after week I was moved by the pitiableness of the bare linoleum-floored sacristy which no flowers could cheer or soften, by the terrible singing I so loved, by the fatigued Bible readings, the lagging emptiness and dilution of the liturgy, the horrifying vacuity of the sermon, and by the fog of dreary senselessness pervading the whole, which existed alongside, and probably caused, the wonder of the fact that we came; we returned; we showed up; week after week, we went through it."

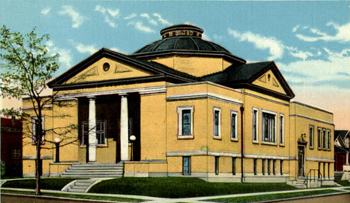

|

My grandmother's church in Ohio. |

Christians have burned books, defended the dubious, supported pseudo-science, and avoided hard questions. In movies like Babette's Feast (1987) and Chocolat (2000), church is portrayed as a place of moralistic, repressed people who never have any fun and who don't really believe what they say they do. In his book What's So Amazing About Grace?, Philip Yancey tells the story of a prostitute who, when she was encouraged to go to church for help, responded, “Church! Why would I ever go there? I already feel terrible about myself. They would just make me feel worse.”

Still others leave church because of the sharp disconnect between our pious platitudes and our unanswered prayers, bitter disappointments, intellectual doubts, nagging questions, or life traumas. In her memoir Leaving Church (2006), Barbara Brown Taylor seems to have left church precisely in order to save her faith.

One response to the church's failures is to long for a return to the "golden age" of the earliest believers. The epistle for this week disabuses us of this romantic fallacy.

Paul taught at Corinth for eighteen months (Acts 18:11). He knew those people well. In his letters to the Corinthians Paul addressed numerous ugly issues — sectarian divisions in which both sides claimed to be more spiritual than the other, boasting about incest ("and of a kind that does not occur even among pagans"), lawsuits between Christians, eating food that had been sacrificed to pagan idols, disarray in worship services, and predatory pseudo-preachers who masqueraded as super-apostles.

The earliest churches were as troubled as our own today. But despite its many faults, and despite the futility of finding a pure or perfect church of any time or place, like Annie Dillard I keep coming back for more church week after week. Why bother?

First, I lower my expectations and expand my horizons. God's kingdom is not identical with the institutional church. At its best, the church mediates and points to God's kingdom, but God often works beyond and in spite of the church.

Jesus compared God's kingdom to a fish net that trawls the sea, catching both the good and the bad, or to wheat and tares that grow together. The inner circle of Jesus's followers included the traitor Judas and the betrayer Peter. "There are many sheep without," wrote Augustine, "and many wolves within."

Furthermore, when I go to church I experience much good — couples working to hold their marriages together, parishioners working for the good of public schools, generosity to the poor, hospital visitation of the sick, efforts at building community in an individualistic society, adoption of orphans, outreach to victims of HIV and AIDS, care for unwed teenage mothers, building schools and hospitals in places that would otherwise never have them, and so on.

Focusing only on our faults distorts the true nature of the church. For all of the barbarities of Spanish colonization, there's a Bartolome de las Casas (1484–1566), a Dominican priest who defended Native Americans for fifty years. For every impulse of greed, there's the selfless compassion of a Mother Teresa, whether known or unknown. For every craven acquiescence to political power, there's a Thomas More (1478–1535) who spoke truth to those powers.

Even though God's kingdom is bigger than the church, in some mysterious manner the church is God's ordained human institution where he has chosen to work.

The most famous (and controversial) expression of this truth comes from Cyprian (200–258), bishop of Carthage in North Africa. In his treatise On the Unity of the Church, he wrote that "outside of the church there is no salvation," and similarly, "you cannot have God for your Father unless you have the Church for your Mother." Protestants might cringe at these words, but both Calvin and Luther quoted them almost verbatim.

|

My childhood church in North Carolina. |

So, I want to situate myself where God has said he is present. Flannery O'Connor said that she sat at her writing desk every morning so that she would be ready if and when an idea came to her. Likewise, in her memoir Ordinary Time, Nancy Mairs writes that she moved beyond her lapsed Catholic faith and returned to church, even though she still had many questions, so that she could "prepare a space into which belief could flood."

Sometimes authentic faith results from rather than precedes fidelity to the church.

Finally, I go to church out of a sense of my own needs. Being a Christian is one of the things in life that you can't do alone.

During the Protestant Reformation, the Renaissance humanist Erasmus (1466–1536) locked horns with Luther over their contrasting views of human nature. Erasmus rejected Luther's pessimistic views of the human will and natural reason, so he stayed put in his deeply troubled Catholic church. "Therefore I will put up with this Church until I see a better one," wrote Erasmus; "and it will have to put up with me, until I become better."

So, I'm thankful for a church, however imperfect, that has welcomed my imperfect self with my imperfect faith.

We should never ignore the church's faults and failures. We should name them, own them, repent of them, and do what we can to correct them. Losing our illusions about church (dis-illusionment) is necessary and good. Thus did Luther, angry about the troubles of medieval Catholicism, offer what Diarmaid MacCulloch calls a "spectacularly disloyal form of loyalty to the church" when he demanded radical reform.

One of our earliest Christian creeds is the Old Roman Creed from the late second century. One of the fragments that predates it reads, "I believe in God the Father Almighty, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, our Lord. And in the Holy Spirit, the holy Church, the resurrection of the flesh."

Such early creeds served as baptismal confessions, as the basic instructional material for teaching, as a summary of our faith, and as affirmations used in public worship. The centrality of the church in such a succinct expression of faith serves as an important reminder. And so with the Benedictine nun Joan Chittister, I aspire to be what she calls "a loyal member of a dysfunctional family."

Image credits: (1) CardCow.com and (2) Fuquay-Varina Presbyterian Church.