A Shocking Request and a Stupendous Claim:

The Baptism of Jesus

For Sunday January 12, 2014

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 42:1–9

Psalm 29

Acts 10:34–43

Matthew 3:13–17

The story of Jesus always surprises us if we observe the obvious. And when we see and hear what's really happening, it can be very unsettling. The baptism of Jesus, and the stories in Matthew's gospel that lead up to it, are a case in point.

Every person has a genealogy, and we all hope that some of our ancestors were important people. Documenting our noteworthy forebears is a status booster, however tenuous the connection.

|

The gospel of Matthew begins with the genealogy of Jesus. Matthew burnishes his credentials by name-dropping Abraham and King David — next to Moses, the two most important people in all of Jewish history. His genealogy lists forty-two men in three sets of fourteen generations each. All nice and neat. Then comes a shock.

Matthew includes five sexually suspicious women in Jesus's family tree. Tamar was widowed twice, then became a victim of incest when her father-in-law Judah abused her as a prostitute (Genesis 38). Rahab was a foreigner and a prostitute who protected the Hebrew spies by lying. Ruth was a foreigner and a widow. Bathsheba was the object of David's adulterous passion and murderous cover-up. Then, of course, there's Mary the mother of Jesus, who was unmarried and pregnant.

Matthew then describes the birth of Jesus through five disturbing dreams. He contrasts Herod "the king of the Jews" with Jesus, whom he also calls "the king of the Jews." You don't need to be a political scientist to know that imperial Rome would have considered that claim an act of political sedition.

And who were the first people to worship the "real" king of the Jews? Another shock — pagan magi from the east worship Jesus, whereas Herod tries to kill Jesus by slaughtering the baby boys of Bethlehem.

The historical obscurity of the magi has encouraged speculation. Matthew doesn't say that there were three of them. The Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BC) said they were a caste of priests from Persia. Others trace them to the Kurds of two millennia ago, which would be a delicious irony in our contemporary geo-political context.

|

By the third century, some people interpreted the magi as three kings, a reading which would provoke another clash of kingdoms: on the one hand, pagan kings who bow down to the newborn king of the Jews, and, on the other hand, king Herod who tries to murder him.

Still more surprises burst the boundaries of this most Jewish of all the gospels. The young family of Jesus escapes to pagan Egypt, the sworn and symbolic enemy of Israel, the iconic place of 430 years of bondage. It's in Egypt that they find refuge and protection.

In the end, king Herod died, about 4 BC, not king Jesus. Jesus returned and settled in the town of Nazareth in the district of Galilee, a village so insignificant that it's not mentioned in the Old Testament, in the historian Josephus (c. 37–100), or in the Jewish Talmud. "Can anything good come from Nazareth?" asked Nathaniel (John 1:46).

Except for Luke's story about the boy Jesus in the temple, these four pages in Matthew are all we know about him before he began his public ministry. He otherwise remains shrouded in historical obscurity for almost thirty years. This part of Jesus's life seems to have been so ordinary and so invisible that it became entirely forgettable.

Eventually, though, there emerged a tension between Jesus's filial identity with God the father and his obedience to his earthly parents. That obedience gave way to a radical rupture, for by the time of his public ministry his own family tried to apprehend him and the entire village of Nazareth tried to kill him as a deranged crackpot (cf. Mark 3:21, Luke 4:29, John 7:5).

That brings us to his baptism. After living in anonymity and obscurity for thirty years, Jesus left his family and joined the movement of his eccentric cousin John.

Whereas John's father had been part of the religious establishment as a priest in the Jerusalem temple, John fled the comforts and corruptions of the city for the loneliness of the desert. Living on the margins of society, both literally and figuratively, he preached "a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins."

|

Contrary to what you might have expected from such an ascetic man and an austere message, the people flocked to John. Even twenty years later in far away Ephesus (1,000 miles by land), people still submitted to the baptism of John (Acts 19:3).

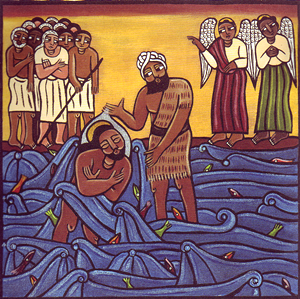

Then another shock — Jesus asks to be baptized by John. This is an explicit role reversal. John had predicted that Jesus would baptize us with a figurative "baptism of fire." And now Jesus asks John for a literal baptism by water.

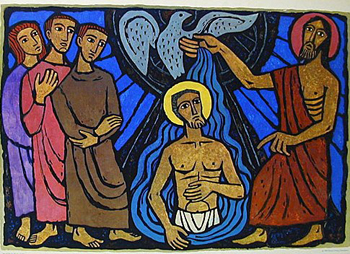

With some important stylistic differences, all four gospels include Jesus's baptism by John: "When all the people were being baptized, Jesus was baptized too. And as he was praying, heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: 'You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.'"

Why did Jesus the greater submit to baptism "for the forgiveness of sin" by John the lesser? Did he need to repent of his own sins?

The earliest witnesses of his baptism asked this question, because in Matthew's gospel John tried to dissuade Jesus: "Why do you come to me? I need to be baptized by you!" Crossan argues that there was an "acute embarrassment" about Jesus's baptism. Even a hundred years later Jesus's baptism troubled some Christians. In the non-canonical Gospel of the Hebrews (c. 80–150 AD), Jesus denies any need to repent, and seems to get baptized to please his mother.

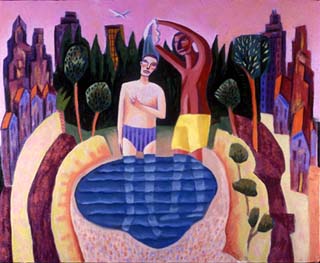

Jesus's baptism inaugurated his public ministry by identifying with "the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem." He identified himself with the faults and failures, the pains and problems, of all the broken people who had flocked to the Jordan River. By wading into the waters with them he took his place beside us.

Not long into his public mission, the sanctimonious religious leaders derided Jesus as a "friend of gluttons and sinners." They were right about that.

|

But none of this comes close to the biggest bombshell of the baptismal story — the stupendous claim of a trinitarian confession.

Jesus's baptismal solidarity with broken people was confirmed by God's affirmation and empowerment. Still wet with water after John had plunged him beneath the Jordan River, Jesus heard a voice and saw a vision — the declaration of God the Father that Jesus was his beloved son, and the descent of God the Spirit in the form of a dove.

The vision and the voice punctuated the baptismal event. They signaled the meaning, the message and the mission of Jesus as he went public after thirty years of invisibility — that by the power of the Spirit, the Son of God embodied his Father's unconditional love of all people everywhere.

Image credits: (1) Third Way Living by Ken Corder; (2) James B. Janknegt, Brilliant Corners ArtFarm; (3) Gymnos Aquatic Saints; and (4) Curious Christian by Matt Stone.