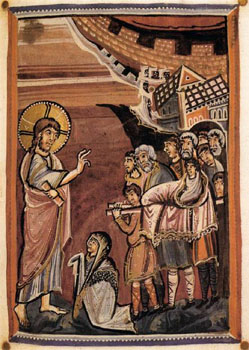

Jesus and the Widow of Nain:

"His Heart Went Out to Her"

For Sunday June 9, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

1 Kings 17:8–16, (17–24) or 1 Kings 17:17–24

Psalm 146 or Psalm 30

Galatians 1:11–24

Luke 7:11–17

Here we are, ten weeks after Easter, and Luke is reminding us of resurrection. We're in ordinary time, that liturgical lull of six months between Pentecost and Advent. But for Luke there's nothing remotely ordinary about Jesus. He's the compassionate servant of God who wields power over death.

The story about the widow of Nain occurs only in Luke. As this week's images show, the story has captivated the imagination of artists for two thousand years. Crusaders and later Franciscans built a church to commemorate the story. Luke places it right after a story about another outsider, the exemplary faith of a Roman soldier. After healing the centurion's servant in Capernaum, Jesus and his disciples walked 25 miles southwest to the village of Nain.

|

Raising the son of the widow of Nain, German Hitda Codex, c. 1020. |

Luke describes how a "large crowd" accompanied Jesus and his disciples. He uses the same Greek word to describe how when they entered the town gate, they met another "large crowd" that was leaving the village. It was a funeral procession. They were leaving Nain because ritual purity prohibited burials inside the city walls. And so the two "large crowds" met at the town gate — the followers of Jesus and the mourners of Nain.

The corpse was "the only son of his mother," which meant that this woman faced double jeopardy. She had been a widow, and now she was childless. As if her fragile life wasn't hard enough, she fell further down the economic scale of protection and provision. All she had to live for and to live by was gone. Perhaps the "large crowd" that accompanied her was indicative of the depth of her tragedy.

When the two crowds met and Jesus encountered the widow, "his heart went out to her" in a spontaneous act of compassion. No one had asked him to do anything. No one had recognized him. But the sights and sounds were too much for Jesus. Moved to compassion, he told her, "Don't cry." He then touched the coffin, raised the man to life, and "gave him back to his mother."

I still remember learning the Greek verb "to have compassion" thirty years ago in seminary — "splagcnizomai." The word occurs a dozen times in the New Testament, only in the gospels. The verb form comes from the noun "splanxna," meaning your bowels, heart, lungs, liver or kidneys, which in that day were the center of human emotions. Throughout the gospels Jesus is a man of compassion.

Raising the son of the widow of Nain, Russian icon. |

As he walked through the villages and saw the crowds afflicted with sickness and disease, "he had compassion on them." When he saw the hungry, "he had compassion on them," healed the sick, and fed the five thousand. When thronged by another "large crowd" of the lame, the blind, the crippled, and the dumb, he told his disciples, "I have compassion for these people." And when he left Jericho followed by yet another "large crowd," and two blind beggars screamed for help, "Jesus had compassion on them" and healed them.

The two most famous parables in the Bible are about compassion. In contrast to the insider religious professionals, the outsider Good Samaritan "had compassion" on the man beaten by thugs. And while the prodigal son "was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him."

Last week I read a post on Twitter to the effect that Christians are supposed to be safe people, reliably compassionate like Jesus, but instead we're often feared as dangerous and judgmental. I read this tweet at the same time that Rick Warren's son committed suicide. Some people expressed compassion for a famous family that had struggled with mental illness for decades, but many others were quick to shoot the wounded.

My favorite novel, Infinite Jest, takes place at the Enfield Tennis Academy, a boarding school where kids hone their skills in the hopes of going pro. One of the characters, LaMont Chu, is so obsessed with tennis fame that he imagines pictures of himself in magazines, television announcers analyzing his stroke in hushed tones, and corporations paying him to wear their logos. He's so obsessed he can't eat, sleep, or even pee. Ambition is eating him alive.

LaMont goes to the academy's guru named Lyle for help. He admits his rabid ambition to Lyle. He's ashamed of his hunger for hype. He feels lost and lonely.

Lyle is the perfectly safe listener. He's fundamentally compassionate with these young tennis prodigies: "the supplicant feels both nakedly revealed and sheltered, somehow, from all possible judgment." LaMont knows that he can spill his guts to Lyle. He knows that he'll receive compassion and not criticism.

|

Raising the son of the widow of Nain, 12th century mosaic, Montreal Cathedral, |

Some of us are not only hard on others; we're hardest on ourselves. Much of Gerard Manley Hopkins' poetry reflects his lifelong struggles with darkness and despair. Converting to Catholicism estranged him from his Anglican family. He burned much of the poetry he had written, and even stopped writing for seven years. After ordination as a Jesuit priest, an assignment in Ireland left him feeling isolated and melancholy, thus giving rise to his so-called "terrible sonnets."

But somewhere in his darkness, Hopkins sensed God's light. He moved beyond self-reproach to divine compassion. One of his poems describes an interior conversation with himself about accepting "God's smile" upon his life.

My own heart let me more have pity on; let

Me live to my sad self hereafter kind,

Charitable; not live this tormented mind

With this tormented mind tormenting yet.

I cast for comfort I can no more get

By groping round my comfortless, than blind

Eyes in their dark can day or thirst can find

Thirst's all-in-all in all a world of wet.Soul, self; come, poor Jackself, I do advise

You, jaded, let be; call off thoughts awhile

Elsewhere; leave comfort root-room; let joy size

At God knows when to God knows what; whose smile

's not wrung, see you; unforseen times rather — as skies

Betweenpie mountains — lights a lovely mile.

Psalm 146 for this week reminds us that there are millions of people in our world who need compassion and care — the oppressed, the hungry, prisoners, the blind, those who are bowed down, the foreigner, the fatherless, and the widow. And in all likelihood, our next door neighbors.

"Be kind," said the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, "for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle."

Image credits: (1) The Edge of the Enclosure; (2) Pravoslavie.ru; and (3) General Board of Discipleship, United Methodist Church.