Communities of Compassion, Then and Now

For Sunday April 15, 2012

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 4:32–35

Psalm 133

1 John 1:1–2:2

John 20:19–31

After a period of doubt and disbelief following the execution of Jesus, and despite threats from the Jewish and Roman authorities, his followers became convinced that "God has raised this Jesus to life, and we are all witnesses of the fact. We cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard" (Acts 2:32, 4:20).

These unschooled and ordinary followers of Jesus proclaimed their message with courage and boldness. In Jerusalem, converts joined the movement en masse, first 3,000 people, then 5,000 (2:41, 4:4). Luke's description of this emergent Jesus-community helps to explain the appeal of their message and its consequent expansion:

All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they shared everything they had. With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and much grace was with them all. There were no needy persons among them. From time to time those who owned lands or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles' feet, and it was distributed to anyone as he had need (Acts 4:32–35).

A few pages earlier Luke describes a similar sort of primitive and voluntary "communalism" (see 2:42–47). And notice how Luke book-ends his narrative about the "acts" of the early believers. The first page of his narrative begins in Jerusalem; on the last page the Jesus story has spread like wild fire to Rome. An obscure Jewish sect has now challenged a global empire. But how?

|

Emperor Hadrian. |

Luke emphasizes the signature characteristic of the Jerusalem believers — in a word, generosity. Their social generosity expressed itself in community, and their financial generosity expressed itself in compassion. Rome boasted many things — military domination, economic power, political peace, a system of carefully engineered roads, and spectacular architecture. But genuine community and human compassion were more radical and powerful than all these glories of Rome.

The first Christians broke down social barriers. They disregarded religious taboos that distinguished between the ritually clean and the unclean, the worthy and the unworthy, the respectable and the disrespectable. They were "one in heart and mind," writes Luke. They subverted normal social hierarchies of wealth, ethnicity, religion, and gender in favor of a radical egalitarianism before God and with each other: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:28).

Their financial generosity expressed itself in compassion toward the needy. Indeed, a few pages later in his account Luke describes famine relief efforts (Acts 11:29). This reputation for financial generosity and compassion still resonated three centuries later. The pagan emperor Julian the Apostate (AD 361–363), who vehemently opposed Christians and stripped them of their rights and privileges, acknowledged: "The godless Galileans feed not only their poor but ours also. Those who belong to us look in vain for the help that we should render them."

|

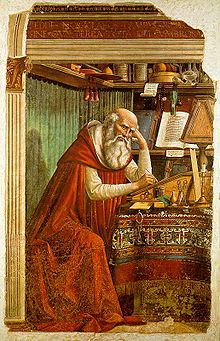

St. Jerome in His Study (1480), by Domenico Ghirlandaio. |

Some people dismiss Luke's descriptions of social and financial generosity as a utopian dream that's impossible to live. That's not true. Many believers have lived this dream, as Garry Wills observes in his book What Jesus Meant (2006): "Eastern monks, the first Franciscans, the Shakers, Catholic Workers, worker priests, base communities [in Latin America], and Christian communities like Jonah House."

Consider these two snap shots, one ancient and one modern.

A generation after the first believers, the Greek Christian Aristides practiced philosophy in Athens. It's tempting to wonder if he was a convert from Paul's ministry in Athens that Luke describes in Acts 17. Jerome tells us that Aristides presented his Apology on behalf of Christianity to Hadrian, emperor of Rome from 117–138.

In his Apology, Aristides contrasts "four classes of people" — Barbarians, Greeks, Jews, and Christians. Here's his description of believers in the early second century:

Wherefore they do not commit adultery nor fornication, nor bear false witness, nor embezzle what is held in pledge, nor covet what is not theirs. They honour father and mother, and show kindness to those near to them; and whenever they are judges, they judge uprightly. They do not worship idols (made) in the image of man; and whatsoever they would not that others should do unto them, they do not to others; and of the food which is consecrated to idols they do not eat, for they are pure. And their oppressors they appease (lit: comfort) and make them their friends; they do good to their enemies; and their women, O King, are pure as virgins, and their daughters are modest; and their men keep themselves from every unlawful union and from all uncleanness, in the hope of a recompense to come in the other world. Further, if one or other of them have bondmen and bondwomen or children, through love towards them they persuade them to become Christians, and when they have done so, they call them brethren without distinction. They do not worship strange gods, and they go their way in all modesty and cheerfulness. Falsehood is not found among them; and they love one another, and from widows they do not turn away their esteem; and they deliver the orphan from him who treats him harshly. And he, who has, gives to him who has not, without boasting. And when they see a stranger, they take him in to their homes and rejoice over him as a very brother; for they do not call them brethren after the flesh, but brethren after the spirit and in God. And whenever one of their poor passes from the world, each one of them according to his ability gives heed to him and carefully sees to his burial. And if they hear that one of their number is imprisoned or afflicted on account of the name of their Messiah, all of them anxiously minister to his necessity, and if it is possible to redeem him they set him free. And if there is among them any that is poor and needy, and if they have no spare food, they fast two or three days in order to supply to the needy their lack of food.

Less than a century after the first believers, an Athenian philosopher bore witness to their community and compassion before Rome's emperor.

|

Julian the Apostate. |

Fast forward to Namibia in southern Africa. During Lent I read a booklet of daily meditations published by Episcopal Relief and Development. One reading described a "mobile hospice ministry" in Namibia run by the Anglican "Mother's Union." Namibian women traveled from "village to village, home to home," to minister to people dying from HIV-AIDS and malaria. Brian Sellers-Peterson writes in Lenten Meditations 2012: "These mobile hospice workers provide basic first aid, binding up wounds, guiding cups of water to the lips of God's children with little time left on earth, holding and hugging those ravaged by the scourge of disease and isolation." This sounds like Luke or Aristides.

The early church wasn't perfect, not by a long shot. After depicting their social and financial generosity, Luke describes Greek Jews complaining about the Aramaic Jews because their widows were being overlooked "in the daily distribution of food." The influx of Gentiles into what amounted to a Jewish sect wreaked havoc. Paul describes factions in Corinth. But at our best, back then and now, the followers of Jesus have a public reputation for community and compassion.

Image credits: (1) Hadrians.com; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.