A Staggering Difference and a Profound Transformation

For Sunday March 4, 2012

Second Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Genesis 17:1–7, 15–16

Psalm 22:23–31

Romans 4:13–25

Mark 8:31–38 or Mark 9:2–9

When Patrick Fermor died last year at the age of ninety-six, many people regarded him as Britain's best travel writer. That reputation came from two books that recount his teenage trek across Europe — A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986). When he was eighteen, Fermor left England with little more than a back pack; three years later he arrived in Istanbul. The BBC once described him as “a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene.”

I recently read Fermor's little book A Time to Keep Silence. With its running commentary on history, culture, art, and architecture, the book fits naturally into the travel literature genre. But his descriptions of visiting four monasteries are much more than that. Fermor moves beyond the mere outer journey of the traveller to explore the inner geography of the human heart.

|

The Abbey of Saint Wandrille. |

Fermor started at the Abbey of St. Wandrille in France, which was founded in 649. His next stop was the 11th-century monastery at Solesmes, famous for its Gregorian chant. He then visited La Grande Trappe, distinct for its strict austerity and total silence. That ambiguous experience made him wonder how a psychiatrist would parse the "manhandling of the delicate machinery of the psyche which these [Trappist] struggles involve." The book ends at the abandoned ruins of the rock-carved monasteries in Turkey.

When Fermor climbed the hill to the gate of St. Wandrille "unknown and unannounced," he was merely looking for a quiet place to write. A monk welcomed him, grabbed his bags, and showed him his quarters: "Here is your cell." Fermor then describes his shock at the "staggering differences" he discovered between life inside the monastery and outside in the world. As Karen Armstrong writes in her introduction to the book, "the monastery represented another world, one that entirely and deliberately reversed the norms of secular life."

|

Abbey of St. Peter at Solesmes. |

In the popular imagination monasteries are gloomy places of misanthropic austerity. Armstrong notes that some people even feel affronted at how monasticism challenges so much of what the world values. "Instead of seeking wealth, comfort, and material success, monks opt for poverty and do not even own their own toothbrushes. Their voluntary celibacy and renunciation of intimacy seem to violate basic human instincts. And they give up their freedom and personal autonomy, vowing obedience to their superiors in a way that is repugnant to the independent ethos of modernity."

This fundamental reversal of worldly values made Fermor's first days at St. Wandrille's difficult. He experienced intense loneliness, depression, and insomnia. But before long the hospitality of the monks and the rhythm of their liturgical life made a profound impact on this self-described "giaour" or unbeliever. By the end of his monastic memoir the paradox was complete. Adapting to the monastic life was hard, but returning to the vulgarity of the world, writes Fermor, was "ten times worse."

|

La Grande Trappe. |

In the gospel for this week Jesus tells his disciples that he must suffer many things, be rejected by the religious establishment, and eventually be killed. "He spoke plainly about this," writes Mark. Peter did what any person acting in the normal ways of the world would have done; he tried to dissuade Jesus from the way of suffering and death. Jesus rebuked him with the harshest of language: "Out of my sight, Satan! You do not have in mind the things of God, but the things of men."

Jesus wasn't obsessed with some masochistic mission. Rather, he embodied like no other person before or after him the mysterious truth that had shocked Fermor in his monastery visits: "Whoever wants to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for me and the gospel will save it. What good is it for a man to gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul?"

In our Lenten disciplines we're not trying to earn God's favor. That's impossible and, more importantly, unnecessary. We're not even trying to improve our moral character. The epistle for this week from Romans, which is Paul's commentary on the Old Testament reading about Abraham, reminds us that all life from God is pure gift and grace. You couldn't earn it even if you were foolish enough to try. The God of Abraham promises him a progeny long after his age would allow it. For Abraham and Sarah long ago and for us today, he "calls those things that do not exist into existence."

|

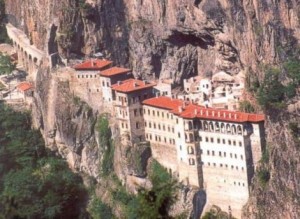

Sumela Monastery in Turkey. |

Instead of works-righteousness or self-reformation, during Lent we make choices that enhance and enrich true life. We're reminded that we can accept or reject God's gifts, cultivate them or ignore them. With our Lenten disciplines, like Fermor we discover where and how life in God's kingdom differs so drastically from life in the world. We explore, for example, how self-sacrifice gives life and how self-indulgence is a will to death. Or we might meditate on the paradoxes of the Peace Prayer, that "it is in giving that we receive; It is in pardoning that we are pardoned; It is in self-forgetting that we find; And it is in dying to ourselves that we are born to eternal life."

A reader from Vermont recently sent me the poem Immersion by Denise Levertov (1923–1997). Along with Fermor's little book, it reminds me that at Lent God speaks and acts in ways that are different from the ways of the world, and different from what I might expect or notice if I don't pay careful attention.

There is anger abroad in the world, a numb thunder,

because of God's silence. But how naive,

to keep wanting words we could speak ourselves,

English, Urdu, Tagalog, the French of Tours,

the French of Haiti.

Yes, that was one way omnipotence chose

to address us-Hebrew, Aramaic, or whatever the patriarchs

chose in their turn to call what they heard. Moses

demanded the word, spoken and written. But perfect freedom

assured other ways of speech. God is surely

patiently trying to immerse us in a different language,

events of grace, horrifying scrolls of history

and the unearned retrieval of blessings lost for ever,

the poor grass returning after drought, timid, persistent.

God's abstention is only from human dialects. The holy voice

utters its woe and glory in myriad musics, in signs and portents.

Our own words are for us to speak, a way to ask and to answer.

Lent is a liberating reminder that I'm not stuck. Because God speaks in new voices and in unexpected ways, change can come. Renewal is possible. And in the ultimate Christian mystery that awaits us a few Sundays from now, even physical death leads to resurrection life.

For further reflection

For two marvelous films about monastic life, see our JwJ reviews of Into Great Silence (2005), about the Monastery Grand Chartreuse that was founded high in the French Alps in 1049. Then there's Of Gods and Men (2010), a story about eight monks in a remote village of Algeria, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes and was nominated for 11 Césars (the French equivalent of the Oscars).

Image credits: (1) 123rf.com; (2) catholicismpure.wordpress.com; (3) MonasteryGreetings.com; and (4) kusadasi.tv.