Love and Listening

A guest essay by The Very Rev. Dr. Jane Shaw, Dean of Grace Cathedral, San Francisco.

For Sunday October 23, 2011

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Deuteronomy 34:1–12 or Leviticus 19:1–2, 15–18

Psalm 90:1–6, 13–17 or Psalm 1

1 Thessalonians 2:1–8

Matthew 22:34–46

Last week I went to a reading by the poet Mary Oliver. In the question and answer session afterwards, she talked about the ordinary despair so many people feel in the face of the enormity of the world’s problems. ‘What can one individual do?’ she asked.

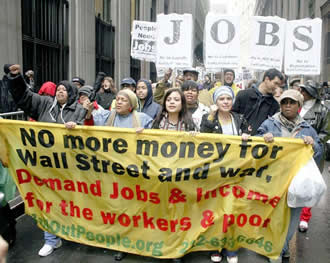

The Wall Street protestors, feeling that same sense of powerlessness, have taken to the streets to express their discontent, and to try and claim their power and their voice. Similar protests have now spread all around the globe.

|

Wall Street Protesters. |

We know that the Pharisees were testing Jesus, but perhaps the one who approached Jesus in this week's gospel had a similar feeling of being overwhelmed when he asked him, "Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?” — for there were 613 precepts in the Torah. How was a person to keep track of them all, let alone prioritize them? Jesus answers with two positive commandments from the Torah: “You shall love the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 6: 5) and “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19: 18). “On these two commandments hang the whole Law and the Prophets.”

Mary Oliver may have answered her own question, as Jesus answered the Pharisee’s, by testifying to the power of love, reading, as she always does, her poem “Wild Geese,” which begins:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

And the American playwright Eve Ensler, commenting on the Wall Street protestors after she had talked to many of them, wrote in the Huffington Post:

"So I came out to face this contradiction: the dehumanization of poverty and the exploitation of capitalism. A block away from the park where the second General Assembly was being held, I heard the words "I love you." The words were as swift as the man who said them, for when I looked back he was already five paces away. But they were as firm as those paces — heavy with determination, purpose, depth. His words permeated the air in Washington Square, and the air on the march, and the air in Zucotti Park. Love was EVERYWHERE!"

But what does this ‘love stuff’ mean? Isn’t it, too, rather amorphous when we are trying to address the world’s needs?

Christians are, indeed, called “to love and serve the world." The prayer at the end of the Eucharist service for Episcopalians says: “And now, God, send us out, to do the work you have given us to do, to love and serve you, as faithful witnesses of Christ our Lord.” We are sent out to put into practice what we have become in the Eucharist: Christ’s body on earth. Ours are the only hands and feet that Christ has now, as the sixteenth-century mystic and Carmelite reformer Teresa of Avila said.

|

Wild geese. |

When we are sent out into the world, when we heed God’s command to love our neighbors as ourselves, we need to ask what that relationship between the Church and the world means. Christianity has always had a paradoxical attitude to the world, and the doctrine of the Incarnation bears it out. On the one hand, God so loved the world that God sent his only begotten son, who healed the sick, fed the poor, raised the dead and lived, preached, ate and made friends in the world alongside ordinary human beings, especially those on the margins of society. On the other hand, those actions of Jesus of Nazareth meant that he eventually came into conflict with the world, as he challenged human priorities and institutions.

As a consequence, many Christians have had a negative view of the world. Some, like the Amish, have chosen to stay away from it, building separate, gathered, utopian communities. They would agree with the author of the epistle to Diognetus, in the middle of the second century, that Christians “live in their own countries, but only as resident aliens.”

Other Christians have assumed that the world is a very bad place, because it is fallen, but they are committed to making it more ‘godly,’ chiefly by converting as many people as possible to Christianity. For them, individual sinners must be saved in order to redeem the world.

Yet other Christians still assume that the world is a bad place, but believe that Christians can make it better: we can build the kingdom of heaven on earth. These Christians do not withdraw from the world, nor do they simply try to grow their own ranks. They get their hands dirty to change things. This perspective has provided the impetus for many wonderful projects, but it has, at times, been paternalistic, assuming still that Christianity has all the answers.

But what if loving our neighbor means that we need to listen to the world and engage with it? What if we realize we do not need to bring Christ to the world, because Christ is already in the world? This creates a different model of loving our neighbor, which is much more about Christians being vulnerable, listening, participating.

|

Congolese women. |

Eve Ensler’s work with women who have been raped in the Congo provides a model for this sort of vulnerable, listening, participative action. Ensler’s organization V-Day, along with UNICEF and Panzi Foundation, are building a community called the City of Joy for women who have survived violence in the Congo. The key thing is that the City is being developed by and run with the women of the Congo, developing their leadership capacity and providing them not only with the tools for healing, but also for economic empowerment, so that they can engage in horticulture and other revenue-generating activities.

I cite this example because it illustrates the ‘engagement with’ and ‘listening to’ mode. And Eve Ensler spoke movingly at my home church of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco a couple of weeks ago about what she has learnt from the women of that community, especially in her own recovery and survival from a cancer that ripped through her body. Healing came not only for the women of the Congo, but also for Ensler when she became truly a part of their community, seeking a solution for the horrors of their lives, yes, but also being vulnerable with them herself.

Here is a simple truth of the Christian faith: God made us, God loves us and God accepts us as we are. We did not have to earn our creation, and we do not have to earn God's love. But God is delighted when we respond to that love. If we are to bring that love to others then we must know something of what it means to be vulnerable with one another and vulnerable with God.

Image credits: (1) BigPeace.com; (2) TakingTheHand.blogspot.com; and (3) Donation4Charity.org.