The Expectation of All Creation:

From Bondage to Decay to Glorious Freedom

For Sunday July 17, 2011

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 28:10–19, Wisdom of Solomon 12:13, 16–19, or Isaiah 44:6–8

Psalm 139:1–12, 23–24, or Psalm 86:11–17

Romans 8:12–25

Matthew 13:24–30, 36–43

About a year before he died, Albert Einstein described himself in a letter to Hans Muehsam as a "deeply religious unbeliever" (March 30, 1954). Einstein was fascinated with the beauty, rationality and complexity of nature. He had a Cosmic Awe for the mystery of the world he strove so mightily to understand. "The eternal mystery of the world," he once wrote, "is its comprehensibility." Einstein repudiated charges that he was an atheist, and criticized the intolerance of those whom he called "the fanatical atheists."

|

The multitude in heaven. |

But Einstein never attended worship services. He didn't pray. He rejected doctrines like miracles and the afterlife. When asked about claims that he believed in a personal God, he categorically rejected the idea as "a lie that is systematically repeated," even though he clearly and consistently denied it (March 24, 1954). Einstein didn't believe in a God who was in any sense personal or who, as he put it, "concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings."

The god of Einstein is a far cry from the God of the psalmist. The God of the psalmist cares deeply and tenderly for every human being. He does in fact care about every person's fate. The psalmist says that you can never flee so far that you are beyond the presence of God's Spirit. Whether I "go up to the heavens" or "make my bed in the depths," "even there your hand will guide me / your right hand will hold me fast."

|

Celestial creatures worship God. |

The darkest day cannot extinguish the light of his love. In some mystery of intimacy, the infinite God knew me before I was born. He fashioned me in my mother's womb, and he lovingly ordains all my days. I might sense this a lot or a little, but it's true nevertheless.

But God is not my Heavenly Valet. If I'm not careful, my narcissistic tendencies fashion a god in my own image who cares only for me or especially for my selfish whims. The Old Testament story this week about Jacob's dream provides a helpful corrective. God cares for me, true enough; but he also cares for each person and every nation.

|

Seven angels with seven plagues. |

When God first called Abraham to form a nation for himself, he said that he would bless not only the Hebrews, but "all peoples on earth" (Genesis 12:3, 22:18). When he repeated his divine call to Abraham's son Isaac, he reiterated his indiscriminate love for all the world: "in you, Isaac, all nations on earth will be blessed" (Genesis 26:5). And when Isaac's son Jacob used a rock for a pillow and dreamed a dream at Bethel, God again repeated verbatim: "In you, Jacob, all peoples on earth will be blessed" (28:14).

The only favoritism that God shows is his unconditional love for each person and every nation. In Ephesians Paul emphasizes this point by making a clever phonetic play on words. God, says Paul, is the patera of every patria — he's the "father (patera) from whom every family (patria) derives its name." God is not my privatistic God. He's not the God of Jews alone, not America's God, or even the God only of Christians. Rather, he's the "father of all fatherhood," the "father of every family," or the "father of the whole human family." He's the God of Muslims, Buddhists, and atheists. Paul even expands God's fatherly favor to "every family in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 3:14–15).

|

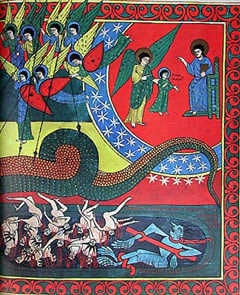

Great red dragon with seven heads and ten horns. |

Paul reinforces this point in this week's epistle. The eastern Orthodox tradition reminds us that Jesus is the pantocrator — the lord not just of people but of all things seen and unseen. Paul combines candor and hope to describe the ambiguous history of all creation. On the one hand, he acknowledges cosmic suffering. Our sufferings provoke a sense of frustration, futility, weakness, and subjugation. We remain "in bondage to decay," says Paul. Like a woman in childbirth, the entire creation groans inwardly and outwardly. The pain can feel unbearable. Paul is thus brutally realistic about our human condition.

But he also exudes confident hope. Believers should live in eager expectation, because our future glory will far eclipse our present suffering. The ultimate destiny of all creation is liberation and freedom, adoption and redemption. The scale and scope of this future hope includes not only each person and every nation but "the whole creation" (Romans 8:12–25; 1 John 2:2).

There's an expansive logic to the Christian good news. God "created all things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities" (Colossians 1:16). He seeks the worship of all "things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth" (Philippians 2:9–11). He will "reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven" (Colossians 1:20). He will sum up or bring together "all things in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 1:10). God delights in bestowing his fatherly favor on "the whole human family in heaven and on earth" (Ephesians 3:15). On earth, under the earth, and in heaven: God was in Christ "reconciling the cosmos to himself" (2 Corinthians 5:19).

|

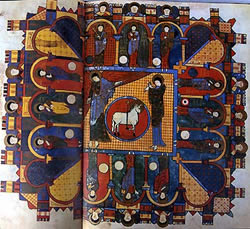

The New Jerusalem. |

The redemption of the entire cosmos is a scandalous idea that faces significant objections. It shocks our sense of justice — doesn't Hitler deserve punishment? It seems to undermine ethics — don't our moral choices have eternal consequences? Universalism has had its adherents, but it's always been a minority position in the church. Most important of all, there are many texts like the gospel for this week that speak of hell and judgment.

For these reasons universalism is best seen as a pious hope rather than a dogmatic certainty. You have to be crazy to teach it but impious not to believe it. On the one hand, the most presumptuous thing we can do is claim to know the mysteries of God. Judgment is his alone. Still, the psalmist for this week rejects the dualist notion that anything exists outside the presence of the omnipresent God of infinite grace and perfect love. Which is to say that we rightly long for the day when death will be destroyed and God will be all in all (1 Cor. 15:28).

NOTE: All the images this week are of 11th-century illuminated manuscripts of the book of Revelation by Stephanus Garsia Placidus, from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Image credits: (1–5) www.Biblical-Art.com.