"A Rabble of Blasphemous Conspirators:"

Proclamation and Reception of the Early Believers

For Sunday June 26, 2011

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 22:1–14 or Jeremiah 28:5–9

Psalm 13 or Psalm 89:1–4, 15–18

Romans 6:12–23

Matthew 10:40–42

After living in total obscurity most of his life, Jesus burst onto the stage of history as the Sent One from God. He traveled throughout all the towns and villages of Galilee teaching, preaching, healing, and announcing the coming of God's reign and rule. Rumors spread like a prairie fire, and before long the dregs of society flocked to him — the diseased, epileptics and paralytics, the poor, prisoners, crazy people with demons, and "those suffering severe pain" (Matthew 4:24).

Jesus healed these people. He said that the kingdom of God meant health and wholeness for everyone. The crowds got bigger. "When Jesus saw the crowds," writes Matthew, "he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd" (10:36). The task was overwhelming, like a ripe harvest without enough farm hands. Ask God for more compassionate healers, said Jesus.

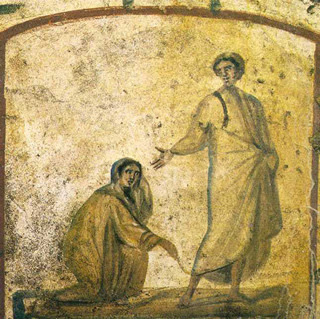

|

Jesus the healer, early fourth century. |

Better yet, he said to his twelve disciples, "you go and do what I have done. As the Father sent me, I now send you." In her book Jesus Freak: Feeding, Healing, Raising the Dead (2010), Sara Miles observes that a "Jesus freak" is a person who lives as if you were Jesus. Feed the poor. Cure the sick. Raise the dead. Cast out demons. Bring the outsiders inside. Make clean all that is dirty.

So the man sent from God sent the twelve disciples to preach, teach, and heal. "He who receives you receives me," he said, "and he who receives me receives the one who sent me. Spread the compassion of God with the same generosity that you have experienced. Freely you have received, freely give. Announce God's peace to every village and home you enter."

Then the story takes a strange turn. Proclamation of the message was one thing. Reception of the messengers was quite another.

Jesus warned that his mission and message were deeply divisive. Religious zealots would flog them. State powers would arrest them. The announcement of divine healing would divide families. In a strange paradox, those who cast out demons would be scape-goated as demon-possessed. Hatreds and persecutions would get so bad, said Jesus, that anyone who offered his sent ones a mere cup of cold water would receive a divine reward (10:42).

|

Jesus the good shepherd, c. 250. |

As the decades rolled by, the messengers of divine healing experienced social harassment. The "Jesus freaks" were viewed by many as just that: freaks. Those who announced God's inclusion of all experienced social exclusion by many.

In one snapshot from the early third century, the Roman lawyer and Christian Minucius Felix pictures how Roman society viewed believers. His dialogue between two friends called The Octavius is a short text, and surprisingly accessible to a general readership.

In the first half of the dialogue, Caecilius presents his pagan criticisms. Since the Christian sect was new and novel, and couldn't claim an ancient pedigree, it was automatically suspect. Christians were "unlettered and unlearned" (Clarke), in Caecilius's words, "utter boors and yokels, ungraced by any manners or culture."

In style and content their scriptures were crude. Believers adhered to absurd doctrines like the resurrection of the body and providence. Rumors about their cannibalism, incest, and infanticide were well known. They were antisocial, avoiding the theater and the games, and apolitical, refusing to run for office. The Christians, said Caecilius, "do not understand their civic duty."

In response, the Christian Octavius barely mentions the Bible, since it would have been rejected out of hand. Nor does he incorporate any theology into his argument. Rather, he appealed to his audience on their own grounds by interacting with dozens of pagan philosophers, poets, and sages. Most interestingly, he doesn't deny that most Christians were poor and uneducated, or that they didn't participate in Roman society.

|

Jesus the teacher, c. 360. |

In the end, the pagan Caecilius converts. Minucius Felix concludes: "I was completely lost in profound amazement at the wealth of proofs, examples, and authoritative quotations he had used to illustrate matter easier to feel than to express; by parrying spiteful critics with their own weapons, the arms of philosophers, he had shown the truth to be so simple as well as so attractive."

Well, maybe. It's a fascinating and complex historical question to what extent the early Christians lived in a sort of social ghetto isolated from mainstream Roman society, and the degree to which they slowly permeated the educated and professional classes. The Octavius, says Clarke, "forms a valuable literary addition to that historical picture of gradual sophistication, of a Church starting on that long, and indeed never-ending, task of coming to terms with its secular milieu" (48).

For further reflection

Compare these two different descriptions of the Christian relationship to Roman society by the same author, Tertullian, writing at the end of the second century:

"We are only of yesterday and have filled everything you have: cities, apartment blocks, forts, towns, marketplaces, even the military camps, tribes, town councils, the palace, the senate, the forum. We have left you only the temples." Apol. 37:4.

Then in his very next chapter: "We Christians shrink from all burning desires for renown and position. . . . there is nothing more foreign to us than affairs of state" (38.3).

And from the Octavius by Felix Minucius, two passages by the pagan critic Caecilius:

"Isn't it scandalous that the [Roman] gods should be mobbed by a gang of outlawed and reckless desperadoes? They have collected from the lowest possible dregs of society the more ignorant fools together with gullible women; they have thus formed a rabble of blasphemous conspirators… They despise our temples as being no more than sepulchers, they spit after our gods, they sneer at our rites, and, fantastic though it is, our priests they pity — pitiable themselves; they scorn the purple robes of public office, though they go about in rags themselves" (8.3-4).

"You do not go to our shows, you take no part in our processions, you are not present at our public banquets, you shrink in horror from our sacred games, from food ritually dedicated by our priests, from drink hallowed by libation poured upon our altars. Such is your dread of the very gods you deny. You do not bind your head with flowers, you do not honor your body with perfumes; ointments you reserve for funerals, but even to your tombs you deny garlands; you anemic, neurotic creatures, you indeed deserve to be pitied — but by our gods. The result is, you pitiable fools, that you have no enjoyment of life while you wait for the new life which you will never have… If you have not been privileged to understand the concerns of a citizen, you most surely have been denied discussion of the affairs of heaven" (12:5-7).

The extent to which early Christians permeated mainstream Roman society is unclear. To what extent do you think it is even good or desirable?

Image credits: (1) Our Lady of Peace Catholic Church, Columbus, Ohio, USA; (2) ReligionFacts.com; and (3) ReligionFacts.com.