|

Grace is Free, But It's Not Cheap

Second Sunday in Lent 2009

For Sunday March 8, 2009

Lectionary

Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Genesis 17:1–7, 15–16

Psalm 22:23–31

Romans 4:13–25

Mark 8:31–38 or 9:2–9

|

St John's Crucifixion Plaque, 7th century Ireland. |

In his book The Ragamuffin Gospel Brennan Manning describes a myth that flourishes today in our churches, the suggestion that Christian discipleship consists of one rousing victory after another. This myth has done believers “incalculable harm,” says Manning, because it misrepresents the way a Christian life is really lived. The myth goes something like this: "On the journey with Jesus I can expect an irreversible, sinless future. Discipleship will be an untarnished success story; life will be an unbroken upward spiral toward holiness."

Personal experience debunks this myth as patently false, but many Christians still chase it as their standard, goal or expectation. Thank God for Lent, and for Mark's Gospel this week, which shows another way. Lent reminds us that the road to Easter resurrection zig zags through the valley of the shadow of death.

Jesus modeled the way for us. After Peter confessed that he was the Christ, Jesus began to predict his death, much to the shock of his disciples who longed for a savior who would vanquish the Romans: “He began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders, chief priests and teachers of the law, and that he must be killed and after three days rise again” (Mark 8:31, NIV). Jesus repeats this prediction two more times in the next few pages (9:31, 10:33).

Coptic icon. |

Resurrection would triumph, but not before suffering, rejection and death. The disciples, who so often in the Gospels misunderstood Jesus and were afraid to ask him questions, got the message loud and clear, for Jesus “spoke plainly about this.” So plainly that Peter rebuked Jesus. “This can never happen to you,” he objected. In perhaps the sharpest rebuke in all of the Gospels, Jesus characterized Peter’s well-intended misunderstanding as satanic.

A second shock then followed when Jesus insisted that this pattern of self-denying suffering was incumbent upon anyone who wanted to follow him. After predicting his own suffering, rejection, and death to the disciples, he then turned to the larger crowd: “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself, take up his cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for me and for the gospel will save it” (Mark 8:34–35).

God’s grace is free, but it's not cheap, for it demands everything. This is a high price to pay, Jesus admits, and the risk-reward logic should pierce your heart: “What good is it for a person to gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul? Or what can a person give in exchange for his soul?” (Mark 8:36–37).

|

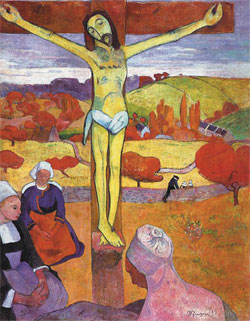

Paul Gaugin, The Yellow Christ, 1889. |

There's a remarkably parallel incident to this Gospel story in the life of Paul. Luke writes that Paul was in a hurry to reach Jerusalem by the day of Pentecost. When their ship landed for a short stay at Caesarea, a prophet named Agabus warned that the Holy Spirit had told him that if Paul went to Jerusalem, he would be bound and handed over to the Gentile authorities. Just as Peter rebuked Jesus who had predicted the sufferings that awaited him in Jerusalem, Paul’s companions begged him to avoid troubles in Jerusalem. His rejoinder is instructive: “Why are you weeping and breaking my heart? I am ready not only to be bound, but also to die in Jerusalem for the name of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 21:8–12). About a week after they landed in Jerusalem Paul was arrested, the first step toward his eventual martyrdom in Rome.

Paul’s post-conversion life imitates Jesus’s model of self-denial and cross-bearing. When Corinthian believers demanded proof of his apostolic authority, he resorted to biting irony. “You want proof,” Paul asked? “Then I will give it to you. I have suffered more hardship, suffering, weakness, persecution, conflict, beatings, imprisonments, sleep depravity, hunger, hard work, lashings, and shipwrecks than anyone else.” Three times he then tells the Corinthians, “If I must boast, I will boast of the things that show my weakness” (2 Corinthians 11:30; 12:5, 9). Even his one moment of glory when he was "caught up into heaven" was accompanied by a “thorn in the flesh.” Paul boasts about his weaknesses, he says, because it is in those weaknesses that he most experiences the grace, love and power of God.1

|

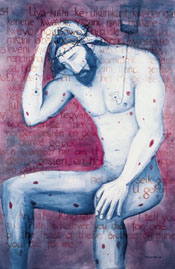

Man of Sorrows: Christ

with AIDS by W. Maxwell Lawton. |

Jesus describes bearing your cross as a necessary part of discipleship. What does that mean? It's understandable that the world promotes self-indulgence over self denial, but oddly enough sometimes the church does too. Martin Luther made a helpful distinction when he contrasted a “theology of glory” (theologia gloriae) with a “theology of the cross” (theologia crucis).

A "theology of glory" is characterized by a triumphalistic posture which seeks to know God only or especially through His mighty acts of power, victory, miracle, and glory. If you pick up almost any popular Christian magazine you will find many examples. The book The Prayer of Jabez, for example, promises you “a front row seat in a life of miracles.” In language of the Old Testament, this mindset lives only for exodus and forgets about exile.

It’s true that we read about God’s mighty acts of power in both the Old and New Testaments, but it was Luther’s great contribution to remind us that beyond all His mighty acts of power, God’s ultimate act of love and self-revelation was through suffering on a cross. A “theology of the cross,” in contrast, insists that we know the Father’s love not so much through awesome miracles or startling outbursts of power, but through times of self-denial, suffering, testing, trials, and human weakness.

|

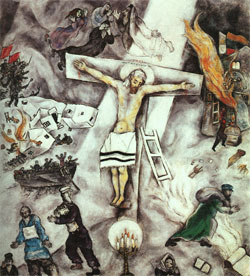

White Crucifixion, Marc Chagall, 1938. |

The language of Jesus has passed into our modern lexicon as a sort of joke, when we tease about having to “bear our cross.” But Jesus meant to tell us something essential rather than trivial about his kingdom. Luke put it this way, after describing an incident when Paul was stoned and left for dead outside the city of Lystra: “We must go through many hardships to enter the kingdom of God” (Acts 14:25). The early desert monastics left us with a wise aphorism: "expect trials until your last breath."

Language like this is almost impossible to understand for western believers in the so-called "first" world, but for the first three hundred years of the church it was the status quo. Lent reminds us that Easter's resurrection victory over sin, death and the devil is certain and on the way, but the journey that Jesus took passes through the via dolorossa.

For further reflection:

* Consider the place of self-denial in a culture of self-indulgence.

* Distinguish between healthy and unhealthy ways of self-denial and self-affirmation.

* Consider the meaning and implications of Luther's contrast between a theology of glory/cross.

* Why are books like The Prayer of Jabez so popular?

[1] The three key passages here are 2 Corinthians 4:7–12; 6:3–10; and 11:1 to 12:10.

Image credits: (1) FaithCentral.net.nz; (2) The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church of Egypt; (3) Carol Gerten-Jackson; (4) www.theotherside.org; and (5) Carol Gerten-Jackson.