|

A Startling Announcement to a Girl from Nazareth

A guest essay by novelist Ron Hansen. Ron's many books include Mariette in Ecstasy and, most recently, Exiles (2008). Among his many honors are a Guggenheim Foundation grant, an Award in Literature from the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a three-year fellowship from the Lyndhurst Foundation. He is currently the Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J. Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Santa Clara University, where he earned an M.A. in Spirituality in 1995.

For Sunday December 21, 2008

Fourth Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B) hotlink: )

2 Samuel 7:1–11, 16

Luke 1:47–55, Psalm 89:1–4, 19–26

Romans 16:25–27

Luke 1:26–38

|

The Annunciation, 12th century Russian icon. |

Each day at noon the bell of Holy Angels Catholic Church slowly gonged, and if we schoolchildren weren’t at lunch or recess we were instructed to stand and recite “The Angelus.”

“The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary,” our teacher would say. Our memorized response was, “And she conceived of the Holy Ghost.” Which was followed by the prayer called the “Hail Mary.”

At the next gong, the teacher recited, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” And we said, “Be it done unto me according to thy word.”

Another “Hail Mary,” another gong, and then the final petition, “The Word was made flesh,” to which we added, “And dwelt amongst us.”

Some fifty years later I still recite “The Angelus” when I hear a church’s noontime bell, and that recitation is a regular reminder of the crucial importance of the announcement and acceptance in our gospel passage from Luke.

***

|

Madonna of Loneliness, Oaxaca, Maxico. |

Readers will recall that earlier, in Luke 1:5–25, the evangelist presented a narrative of the childless couple Zechariah and Elizabeth. Like Sarah in the Book of Genesis, Elizabeth is shamed in that culture for not having offspring, but she is old now, and increasingly hopeless. But when Zechariah, a righteous priest, is offering incense in the holy place of the temple tabernacle, a messenger of the Lord named Gabriel greets him with the announcement that his prayer has been heard and his wife will give birth to a son named John who will become a great prophet like Elijah.

Six months after Elizabeth becomes pregnant, the same messenger (Greek angelos) greets not a wistful, elderly father, but a surprised girl. She was probably no more than fourteen, is not characterized as “righteous” in her religious observances, and is not visited in holy surroundings in the metropolis of Jerusalem, but in presumably humble circumstances in an insignificant northern village called Nazareth. But Gabriel tells Mary she has found favor with God, that she will conceive a son and name him Jesus, and that he will rule a dynasty, fulfilling all the ancient expectations for a Jewish Messiah.

I find Mary’s follow-up question rather confusing in human terms since we have been told she has a fiancé named Joseph. She asks how she, a virgin, could possibly conceive a child. Wouldn’t such a bride-to-be in those times presume that she could become pregnant after her marriage is consummated, and that the angel was foretelling that not-too-far-off event?

|

African Madonna. |

But Mary seems to have intuited something more immediate, and she’s right, for Gabriel is foretelling a miracle. In Luke’s poetic and allusive phrasing, the messenger says, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. Therefore the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God.” And in case she doubted his veracity, he offers as proof Elizabeth, Mary’s kinswoman in Jerusalem, who is pregnant in her old age “for nothing will be impossible for God.”

Though it isn’t clear from their dialogue, a choice seems to have been presented to the girl and she accepts the responsibility of the child with perfect acquiescence, complementing Gabriel’s, “Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son” with her own, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word.”

***

In the musical comedy Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, David Yazbek composed a lovely waltz of a ballad with the lyrics:

Look at the way the moon behaves.

Look at the way she paints

A silver ribbon on the waves.

One thing I've learned and I'll share with you –Nothing is too wonderful to be true.

|

Chinese Madonna. |

Since the first century after Luke’s gospel was written, skeptics have found the virginal conception too wonderful to be true, and it remains a source of extreme contention even now. Some note that miraculous circumstances surrounding the births of illustrious people were a convention of Hellenistic literature, with which Luke was familiar. Some read the gospel passage from Luke as merely metaphorical: that the infant Jesus was the product of natural sexual intercourse between Joseph and Mary, and that act of love was exquisitely and uniquely blessed by the Holy Spirit. But Matthew’s gospel, which provides the only other infancy narrative, opts for a miraculous interpretation similar to Luke’s — this one from the prospective husband’s point of view as Joseph is told in a dream “do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.” And the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, circa 150 C.E., contributes an account of how Mary herself was gifted to Joachim and Anna just as John the Baptist was gifted to Zechariah and Elizabeth. In gratitude Anna presented the child to the temple at the age of three, and though Mary later married an elder named Joseph, the infancy gospel of James maintains her virginity was perpetual.

In Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary, Marina Warner notes the swift evolution of perspectives on the Mother of Jesus as she shifts from being an unnamed person whom the evangelist Mark and the Pauline letters seem either indifferent to or unacquainted with, to being esteemed in Luke and John and the patristic tradition as the first disciple, the ideal Christian, the new Eve, the personification of Israel, and the iconic symbol of the Church itself.

We have no way of knowing now if Mary’s elevation to the highest degree of holiness is the consequence of fresh factual information unavailable to the earlier New Testament writers, or the result of insight, inspiration, deepening piety, or a yearning for a feminine face of God. And it seems to me not to matter.

|

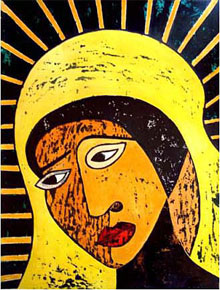

Black Madonna. |

The French philosopher Paul Ricouer argued for a “second naiveté.” The first naiveté occurs when we project our own constructs and fancies into a literary text, and he argued that we should be suspicious of that impulse. But Ricouer secondly cautioned that we also have to forget theologizing and critiquing, adopting an almost childish innocence in order to make ourselves available to a text’s scenes and symbols so that they can have their intended effect on us.

Each of the evangelists, after all, was writing for the heart, not the head. Each was trying in his gospel to communicate overwhelming, world-changing feelings of awe, reverence, gratitude, and continuing need for Christ, who taught us the value of holy obedience and submission to Love. We see the source of that willingness and vulnerability in the girl from Nazareth and the scene of “Annunciation.”

Nothing is too wonderful to be true.

For further reflection:

* How have you understood Mary's place in the Gospels?

* What might we gain from the particular emphases of the Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant traditions about Mary?

* See Jaroslav Pelikan, Mary Through the Centuries; Her Place in the History of Culture.

Image credits: (1) Dept. of Foreign Languages and Literatures, Auburn University; (2) The Art of Mexico; (3) The National Archives; (4) Lake Forest College, Lake Forest, Illinois; and (5) Laura James Art.