|

The Subversive Song of the Mother of God:

Mary's Magnificat

For Sunday December 14, 2008

Third Sunday in Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 61:1–4, 8–11

Psalm 126 or Luke 1:47–55

1 Thessalonians 5:16–24

John 1:6–8, 19–28

|

The Visitation of Mary by the angel Gabriel, Giotto di Bondone, 1302-1305. |

If you've ever felt left behind financially, there might be a reason. Since 1994, the non-partisan United for a Fair Economy has tracked the differential between the pay of CEOs and average workers. Its annual Labor Day report noted that in 2008, "average CEO pay was 344 times the pay of an average US worker." If the federal minimum wage had risen as fast as CEO pay since 1990, the lowest paid workers in the US would be earning about $23 an hour today, not $6.55 an hour.

People disagree about how to redress the disparities between the rich and the poor; but whether we engage these matters is, for the Christian, crystal clear. In the Advent Scriptures for this week, God looks and feels biased. "I, the Lord, love justice; I hate robbery and iniquity" (Isaiah 61:8). The 1.9 million Americans who lost their jobs in 2008, the 46 million people without health insurance, or the 30 million people living with HIV, are all distinctly Christmas issues.

God takes sides, and not just about wealth. These Advent texts are so uncompromising that it's tempting to "spiritualize" them in order to soften them. Instead, we should take them at face value as a declaration that the advent of God's kingdom at Christmas, through a baby born in a barn, subverts our ordinary ways of doing political and socio-economic business.

In Luke's Gospel, the pregnant teenager Mary, the mother of Jesus, moves from the deeply personal to the explicitly political in her famous Magnificat (the first word in the Latin text, "magnifies"). God, Mary exclaims, "has been mindful of the humble state of His servant. . . the Mighty One has done great things for me." This peasant girl who a few months later would bear the Son of God then praises God the Mighty One because He has "brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things but has sent the rich away empty" (Luke 1:48–49, 52–53).

|

Saint Ambrose refuses Theodosius entrance to the Cathedral of Milan. |

When I was in grad school, one of my professors recalled how his friends were amazed that he had quit his radically leftist politics. "I told them," he said, "that the most radically political thing I could do was to pray." Prayer as politics?! For the longest time I had no clue what he meant, but then I began to pay attention to a simple but profound reading of Biblical texts like Mary's Magnificat. No wonder that in the 1980s the government of Guatemala prohibited the public reading of the subversive Magnificat — if Jesus is Lord, and that's the Christmas message, then Caesar, Herod, Pharaoh, Pilate, and Mammon are not lords. They are posers that should be deposed.

A few pages after the Magnificat, Luke records the first public words spoken by Jesus, who expands the breadth of God's biases far beyond wealth and political power. After his temptation in the desert, Jesus "returned to Galilee in the power of the Spirit." One sabbath he entered a synagogue in Nazareth where he had grown up, and when he was invited to speak he unrolled a scroll and read from the poetry of Isaiah for this week (Isaiah 61:1–3):

The Spirit of the Sovereign Lord is on me,

because the Lord has anointed me

to preach good news to the poor.

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim freedom for the captives

and release for the prisoners,

to proclaim the year of the Lord's favor

and the day of vengeance of our God,

to comfort all who mourn,

and provide for those who grieve in Zion—

to bestow on them a crown of beauty

instead of ashes,

the oil of gladness

instead of mourning,

and a garment of praise

instead of a spirit of despair.

When Jesus finished, writes Luke, he rolled up the scroll, handed it to the attendant, and sat down. With "the eyes of everyone in the synagogue fastened on him," Jesus then dropped a bombshell: "Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing." That is, His entire life, death and resurrection were given to fulfill these ancient words of Isaiah.

Many saints have put these words into action. Saint Basil the Great (330–379) served as Bishop of Caesarea in central Turkey. In 372 the emperor Valens sent his proxy Modestus to Caesarea, where he summoned the frail but fiery Basil. Basil dumbfounded Valens with his boldness in a famous incident recorded in his biography. When Modestus threatened Basil with confiscation, exile, torture, and death, Basil stood firm. Modestus remarked that no one had ever spoken to him so rashly, to which Basil replied, "Perhaps you have never met a bishop before."

One of ten children born into a wealthy family, Basil experienced a crisis of faith provoked by his sister Macrina who challenged him about his worldly ambition, saying he was “puffed up beyond measure with the pride of oratory.” Basil relates how he "then read the Gospel, and saw there that a great means of reaching perfection was the selling of one's goods, the sharing of them with the poor, the giving up of all care for this life, and the refusal to allow the soul to be turned by any sympathy towards things of earth" (Ep. ccxxiii).

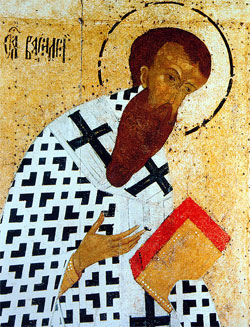

|

St. Basil the Great. |

Basil distinguished himself as a pastor, theologian, writer, and administrator, but many remember him most for his outspoken advocacy of the oppressed, the brokenhearted, and those burdened with what Isaiah 61:3 calls "a spirit of despair." He excommunicated people who owned houses of prostitution, and objected to usury and unjust taxes. During a famine in the years 367–368, he sold his family inheritance to feed the starving. Basil built hospitals to care for the sick, the xenodocheion or "houses for strangers," and the ptocheion or "places for the poor." These institutions became so effective that the pagan emperor (and Basil's former classmate) Julian the Apostate modeled his own welfare efforts after these Christian ones. Basil also did menial work in the kitchens, and objected to any distinctions between Jew and Christian, rich and poor. In his sermons entitled Against the Rich he blasted people who hoarded wealth while the poor starved, who adorned their horses with luxurious finery while their neighbors wore tattered rags, and who let corn rot in granaries and be eaten by rats rather than use it to help the poor: “What kind of punishment, do you think, is deserved by a man who passes the hungry without giving them a sign?”

Mary and Basil, following Jesus the Lord, lived and spoke about the biases of God's heart. They raised their voices in prophetic protests. Beyond that they extended compassionate care to the weak and the marginal. In doing so they signaled the advent of God's kingdom and a reversal of the ordinary ways of the world.

For further reflection:

* Cf. Jaroslav Pelikan, Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture (1998).

* In what sense, if at all, does God favor the poor and oppose the rich?

* Can you recall an instance when a spiritual leader rebuked a powerful person?

Image credits: (1) Olga's Gallery; (2) Tradition in Action; and (3) Orthodox Church in America.